America’s History: Printed Page 360

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 328

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 319

Black Social Thought: Uplift, Race Equality, and Rebellion

Beginning in the 1790s, leading African Americans in the North advocated a strategy of social uplift, encouraging free blacks to “elevate” themselves through education, temperance, and hard work. By securing “respectability,” they argued, blacks could become the social equals of whites. To promote that goal, black leaders — men such as James Forten, a Philadelphia sailmaker; Prince Hall, a Boston barber; and ministers Hosea Easton and Richard Allen — founded an array of churches, schools, and self-help associations. Capping this effort, John Russwurm and Samuel D. Cornish of New York published the first African American newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, in 1827.

The black quest for respectability elicited a violent response in Boston, Pittsburgh, and other northern cities among whites who refused to accept African Americans as their social equals. “I am Mr. ______’s help,” a white maid informed a British visitor. “I am no sarvant; none but negers are sarvants.” Motivated by racial contempt, white mobs terrorized black communities. The attacks in Cincinnati were so violent and destructive that several hundred African Americans fled to Canada for safety.

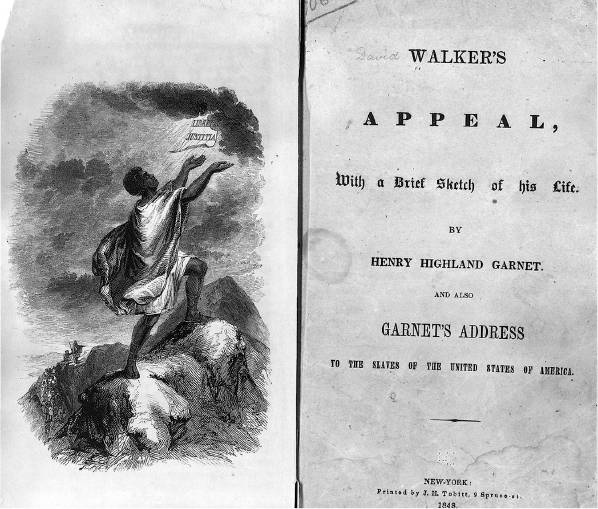

David Walker’s Appeal Responding to the attacks, David Walker published a stirring pamphlet, An Appeal … to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829), protesting black “wretchedness in this Republican Land of Liberty!!!!!” Walker was a free black from North Carolina who had moved to Boston, where he sold secondhand clothes and copies of Freedom’s Journal. A self-educated author, Walker ridiculed the religious pretensions of slaveholders, justified slave rebellion, and in biblical language warned of a slave revolt if justice were delayed. “We must and shall be free,” he told white Americans. “And woe, woe, will be it to you if we have to obtain our freedom by fighting. … Your destruction is at hand, and will be speedily consummated unless you repent.” Walker’s pamphlet quickly went through three printings and, carried by black merchant seamen, reached free African Americans in the South.

In 1830, Walker and other African American activists called a national convention in Philadelphia. The delegates refused to endorse either Walker’s radical call for a slave revolt or the traditional program of uplift for free blacks. Instead, this new generation of activists demanded freedom and “race equality” for those of African descent. They urged free blacks to use every legal means, including petitions and other forms of political protest, to break “the shackles of slavery.”

Nat Turner’s Revolt As Walker threatened violence in Boston, Nat Turner, a slave in Southampton County, Virginia, staged a bloody revolt — a chronological coincidence that had far-reaching consequences. As a child, Turner had taught himself to read and had hoped for emancipation, but one new master forced him into the fields, and another separated him from his wife. Becoming deeply spiritual, Turner had a religious vision in which “the Spirit” explained that “Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.” Taking an eclipse of the sun in August 1831 as an omen, Turner and a handful of relatives and friends rose in rebellion and killed at least 55 white men, women, and children. Turner hoped that hundreds of slaves would rally to his cause, but he mustered only 60 men. The white militia quickly dispersed his poorly armed force and took their revenge. One company of cavalry killed 40 blacks in two days and put 15 of their heads on poles to warn “all those who should undertake a similar plot.” Turner died by hanging, still identifying his mission with that of his Savior. “Was not Christ crucified?” he asked.

Deeply shaken by Turner’s Rebellion, the Virginia assembly debated a law providing for gradual emancipation and colonization abroad. When the bill failed by a vote of 73 to 58, the possibility that southern planters would voluntarily end slavery was gone forever. Instead, the southern states toughened their slave codes, limited black movement, and prohibited anyone from teaching slaves to read. They would meet Walker’s radical Appeal with radical measures of their own.

CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How and why did African American efforts to achieve social equality change between 1800 and 1840?