America’s History: Printed Page 361

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 329

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 320

Evangelical Abolitionism

Rejecting Walker’s and Turner’s resort to violence, a cadre of northern evangelical Christians launched a moral crusade to abolish the slave regime. If planters did not allow blacks their God-given status as free moral agents, these radical Christians warned, they faced eternal damnation at the hands of a just God.

William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Weld, and Angelina and Sarah Grimké The most determined abolitionist was William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879). A Massachusetts-born printer, Garrison had worked during the 1820s in Baltimore on an antislavery newspaper, the Genius of Universal Emancipation. In 1830, Garrison went to jail, convicted of libeling a New England merchant engaged in the domestic slave trade. In 1831, Garrison moved to Boston, where he immediately started his own weekly, The Liberator (1831–1865), and founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society.

Influenced by a bold pamphlet, Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition (1824), by an English Quaker, Elizabeth Coltman Heyrick, Garrison demanded immediate abolition without compensation to slaveholders. “I will not retreat a single inch,” he declared, “AND I WILL BE HEARD.” Garrison accused the American Colonization Society of perpetuating slavery and assailed the U.S. Constitution as “a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell” because it implicitly accepted racial bondage.

In 1833, Garrison, Theodore Weld, and sixty other religious abolitionists, black and white, established the American Anti-Slavery Society. The society won financial support from Arthur and Lewis Tappan, wealthy silk merchants in New York City. Women abolitionists established separate groups, including the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, founded by Lucretia Mott in 1833, and the Anti-Slavery Conventions of American Women, a network of local societies. The women raised money for The Liberator and carried the movement to the farm villages and small towns of the Midwest, where they distributed abolitionist literature and collected thousands of signatures on antislavery petitions.

Abolitionist leaders launched a three-pronged plan of attack. To win the support of religious Americans, Weld published The Bible Against Slavery (1837), which used passages from Christianity’s holiest book to discredit slavery. Two years later, Weld teamed up with the Grimké sisters — Angelina, whom he married, and Sarah. The Grimkés had left their father’s plantation in South Carolina, converted to Quakerism, and taken up the abolitionist cause in Philadelphia. In American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (1839), Weld and the Grimkés addressed a simple question: “What is the actual condition of the slaves in the United States?” Using reports from southern newspapers and firsthand testimony, they presented incriminating evidence of the inherent violence of slavery. Angelina Grimké told of a treadmill that South Carolina slave owners used for punishment: “One poor girl, [who was] sent there to be flogged, and who was accordingly stripped naked and whipped, showed me the deep gashes on her back — I might have laid my whole finger in them — large pieces of flesh had actually been cut out by the torturing lash.” Filled with such images of pain and suffering, the book sold more than 100,000 copies in a single year.

The American Anti-Slavery Society To spread their message, the abolitionists turned to mass communication. Using new steam-powered presses to print a million pamphlets, the American Anti-Slavery Society carried out a “great postal campaign” in 1835, flooding the nation, including the South, with its literature.

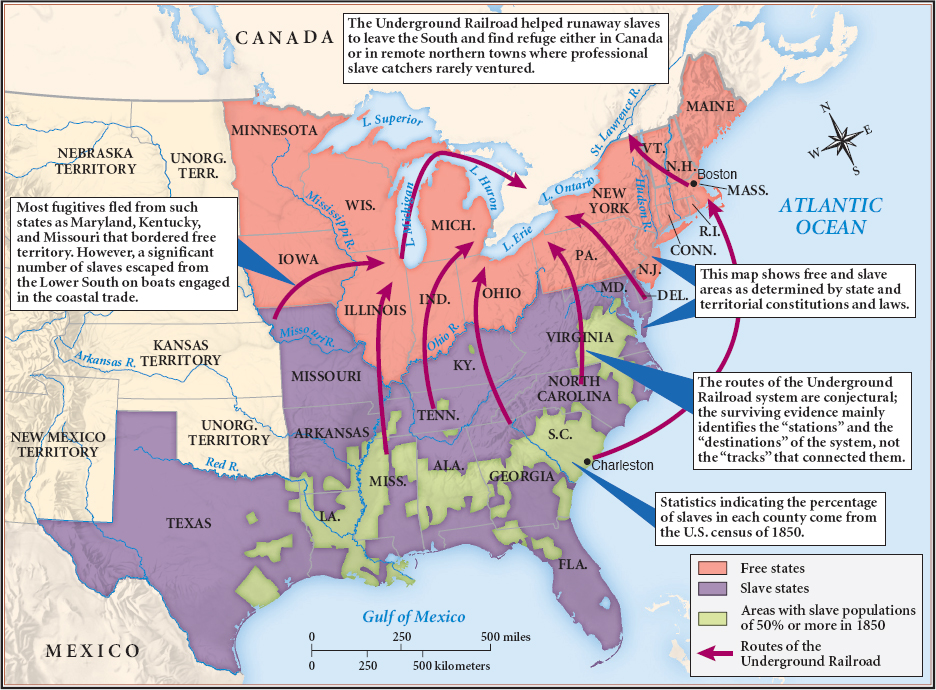

The abolitionists’ second tactic was to aid fugitive slaves. They provided lodging and jobs for escaped blacks in free states and created the Underground Railroad, an informal network of whites and free blacks in Richmond, Charleston, and other southern towns that assisted fugitives (Map 11.3). In Baltimore, a free African American sailor loaned his identification papers to future abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who used them to escape to New York. Harriet Tubman and other runaways risked re-enslavement or death by returning repeatedly to the South to help others escape. “I should fight for … liberty as long as my strength lasted,” Tubman explained, “and when the time came for me to go, the Lord would let them take me.” Thanks to the Railroad, about one thousand African Americans reached freedom in the North each year.

There, they faced an uncertain future because most whites continued to reject civic or social equality for African Americans. Voters in six northern and midwestern states adopted constitutional amendments that denied or limited the franchise for free blacks. “We want no masters,” declared a New York artisan, “and least of all no negro masters.” Moreover, the Fugitive Slave Law (1793) allowed owners and their hired slave catchers to seize suspected runaways and return them to bondage. To thwart these efforts, white abolitionists and free blacks formed mobs that attacked slave catchers, released their captives, and often spirited them off to British-ruled Canada, which refused to extradite fugitive slaves.

A political campaign was the final element of the abolitionists’ program. Between 1835 and 1838, the American Anti-Slavery Society bombarded Congress with petitions containing nearly 500,000 signatures. They demanded the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, an end to the interstate slave trade, and a ban on admission of new slave states.

Thousands of deeply religious farmers and small-town proprietors supported these efforts. The number of local abolitionist societies grew from two hundred in 1835 to two thousand by 1840, with nearly 200,000 members, including many transcendentalists. Emerson condemned Americans for supporting slavery, and Thoreau, viewing the Mexican War as a naked scheme to extend slavery, refused to pay taxes and submitted to arrest. In 1848, he published “Resistance to Civil Government,” an essay urging individuals to follow a higher moral law. The black abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet went further; his Address to the Slaves of the United States of America (1841) called for “Liberty or Death” and urged slave “Resistance! Resistance! Resistance!”

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did the ideology and tactics of the Garrisonian abolitionists differ from those of the antislavery movements discussed in Chapters 6 and 8?