America’s History: Printed Page 363

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 332

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 323

Opposition and Internal Conflict

Still, abolitionists remained a minority, even among churchgoers. Perhaps 10 percent of northerners and midwesterners strongly supported the movement, and only another 20 percent were sympathetic to its goals.

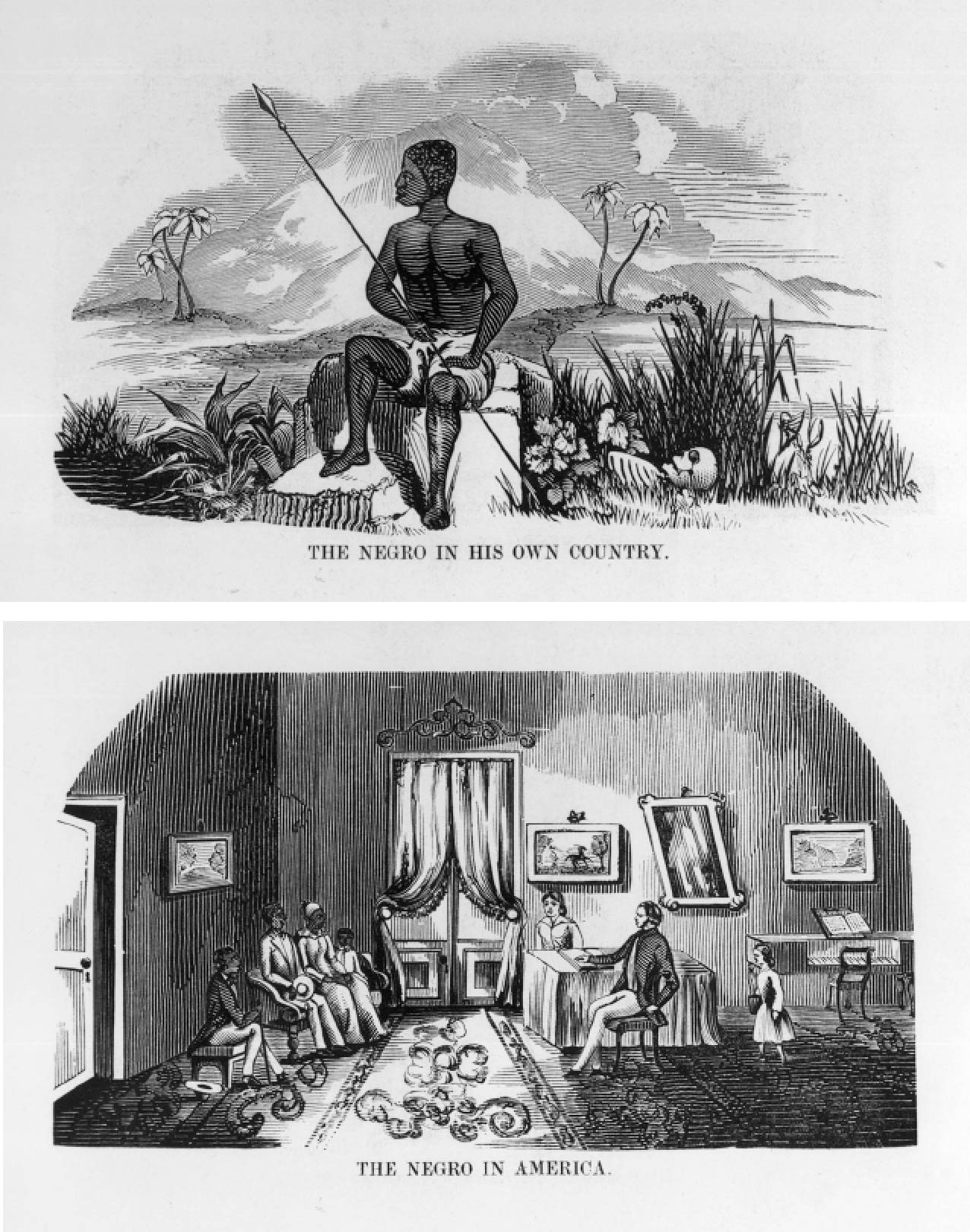

Attacks on Abolitionism Slavery’s proponents were more numerous and equally aggressive. The abolitionists’ agitation, ministers warned, risked “embroiling neighborhoods and families — setting friend against friend, overthrowing churches and institutions of learning, embittering one portion of the land against the other.” Wealthy men feared that the attack on slave property might become an assault on all property rights, conservative clergymen condemned the public roles assumed by abolitionist women, and northern wage earners feared that freed blacks would work for lower wages and take their jobs. Underlining the national “reach” of slavery, northern merchants and textile manufacturers supported the southern planters who supplied them with cotton, as did hog farmers in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois and pork packers in Cincinnati and Chicago who profited from lucrative sales to slave plantations. Finally, whites almost universally opposed “amalgamation,” the racial mixing and intermarriage that Garrison seemed to support by holding meetings of blacks and whites of both sexes.

Racial fears and hatreds led to violent mob actions. White workers in northern towns laid waste to taverns and brothels where blacks and whites mixed, and they vandalized “respectable” African American churches, temperance halls, and orphanages. In 1833, a mob of 1,500 New Yorkers stormed a church in search of Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Another white mob swept through Philadelphia’s African American neighborhoods, clubbing and stoning residents and destroying homes and churches. In 1835, “gentlemen of property and standing” — lawyers, merchants, and bankers — broke up an abolitionist convention in Utica, New York. Two years later, a mob in Alton, Illinois, shot and killed Elijah P. Lovejoy, editor of the abolitionist Alton Observer. By pressing for emancipation and equality, the abolitionists had revealed the extent of racial prejudice and had heightened race consciousness, as both whites and blacks identified across class lines with members of their own race.

Racial solidarity was especially strong in the South, where whites banned abolitionists. The Georgia legislature offered a $5,000 reward for kidnapping Garrison and bringing him to the South to be tried (or lynched) for inciting rebellion. In Nashville, vigilantes whipped a northern college student for distributing abolitionist pamphlets; in Charleston, a mob attacked the post office and destroyed sacks of abolitionist mail. After 1835, southern postmasters simply refused to deliver mail suspected to be of abolitionist origin.

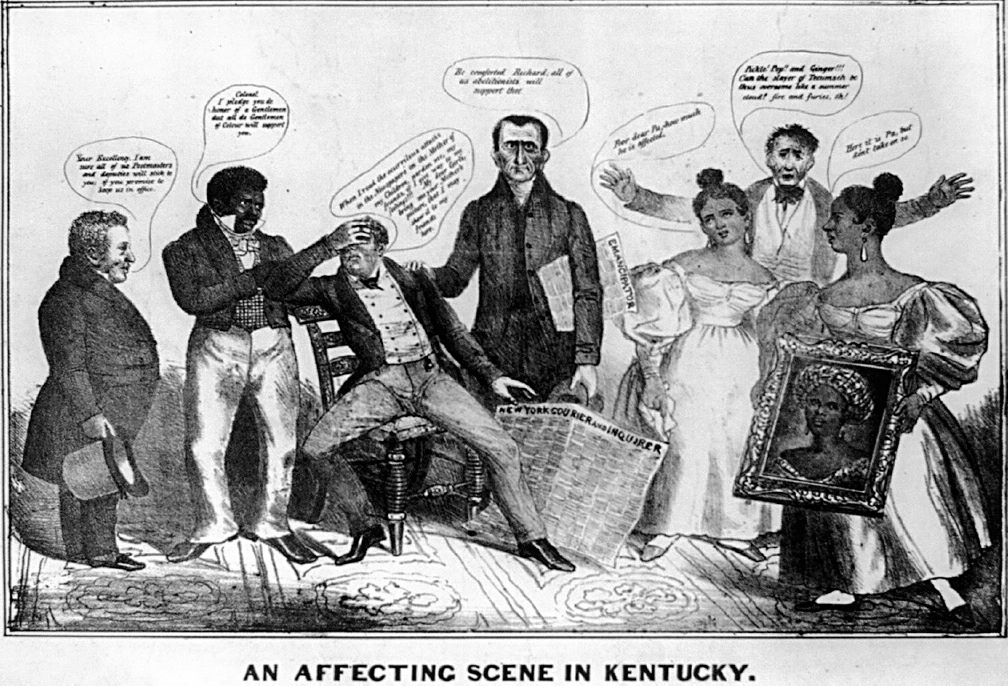

Politicians joined the fray. President Andrew Jackson, a longtime slave owner, asked Congress in 1835 to restrict the use of the mails by abolitionist groups. Congress refused, but in 1836, the House of Representatives adopted the so-called gag rule. Under this informal agreement, which remained in force until 1844, the House automatically tabled antislavery petitions, keeping the explosive issue of slavery off the congressional stage.

Internal Divisions Assailed by racists from the outside, evangelical abolitionists fought among themselves over gender issues. Many antislavery clergymen opposed an activist role for women, but Garrison had broadened his reform agenda to include pacifism, the abolition of prisons, and women’s rights: “Our object is universal emancipation, to redeem women as well as men from a servile to an equal condition.” In 1840, Garrison’s demand that the American Anti-Slavery Society support women’s rights split the abolitionist movement. Abby Kelley, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, among others, remained with Garrison in the American Anti-Slavery Society and assailed both the institutions that bound blacks and the customs that constrained free women.

Garrison’s opponents founded a new organization, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which turned to politics. Its members mobilized their churches to oppose racial bondage and organized the Liberty Party, the first antislavery political party. In 1840, the new party nominated James G. Birney, a former Alabama slave owner, for president. Birney and the Liberty Party argued that the Constitution did not recognize slavery and, consequently, that slaves became free when they entered areas of federal authority, such as the District of Columbia and the national territories. However, Birney won few votes, and the future of political abolitionism appeared dim.

Popular violence in the North, government-aided suppression in the South, and internal schisms stunned the abolitionist movement. By melding the energies and ideas of evangelical Protestants, moral reformers, and transcendentalists, it had raised the banner of antislavery to new heights, only to face a hostile backlash. “When we first unfurled the banner of The Liberator,” Garrison admitted, “it did not occur to us that nearly every religious sect, and every political party would side with the oppressor.”

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

Which groups of Americans opposed the abolitionists, and why did they do so?