America’s History: Printed Page 367

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 336

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 327

From Black Rights to Women’s Rights

As women addressed controversial issues such as moral reform and emancipation, they faced censure over their public presence. Offended by this criticism, which revealed their own social and legal inferiority, some women sought full freedom for their sex.

Abolitionist Women Women were central to the antislavery movement because they understood the special horrors of slavery for women. In her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, black abolitionist Harriet Jacobs described forced sexual intercourse with her white owner. “I cannot tell how much I suffered in the presence of these wrongs,” she wrote. According to Jacobs and other enslaved women, such sexual assaults incited additional cruelty by their owners’ wives, who were enraged by their husbands’ promiscuity. In her best-selling novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Harriet Beecher Stowe pinpointed the sexual abuse of women as a profound moral failing of the slave regime.

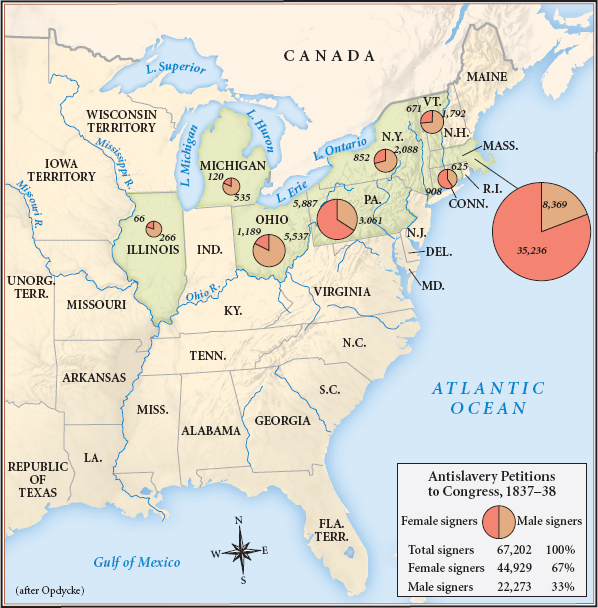

As Garrisonian women attacked slavery, they frequently violated social taboos by speaking to mixed audiences of men and women. Maria W. Stewart, an African American, spoke to mixed crowds in Boston in the early 1830s. As abolitionism blossomed, scores of white women delivered lectures condemning slavery, and thousands more made home “visitations” to win converts to their cause (Map 11.4). When Congregationalist clergymen in New England assailed Angelina and Sarah Grimké for such activism in a Pastoral Letter in 1837, Sarah Grimké turned to the Bible for justification: “The Lord Jesus defines the duties of his followers in his Sermon on the Mount … without any reference to sex or condition,” she replied: “Men and women were CREATED EQUAL; both are moral and accountable beings and whatever is right for man to do, is right for woman.” In a pamphlet debate with Catharine Beecher (who believed that women should exercise authority primarily as wives, mothers, and schoolteachers), Angelina Grimké pushed the argument beyond religion by invoking Enlightenment principles to claim equal civic rights:

It is a woman’s right to have a voice in all the laws and regulations by which she is governed, whether in Church or State. … The present arrangements of society on these points are a violation of human rights, a rank usurpation of power, a violent seizure and confiscation of what is sacredly and inalienably hers.

By 1840, female abolitionists were asserting that traditional gender roles resulted in the domestic slavery of women. “How can we endure our present marriage relations,” asked Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “[which give a woman] no charter of rights, no individuality of her own?” As reformer Ernestine Rose put it: “The radical difficulty … is that women are considered as belonging to men.” Having acquired a public voice and political skills in the crusade for African American freedom, thousands of northern women now advocated greater rights for themselves.

Seneca Falls and Beyond During the 1840s, women’s rights activists devised a pragmatic program of reform. Unlike radical utopians, they did not challenge the institution of marriage or the conventional division of labor within the family. Instead, they tried to strengthen the legal rights of married women by seeking legislation that permitted them to own property (America Compared). This initiative won crucial support from affluent men, who feared bankruptcy in the volatile market economy and wanted to put some family assets in their wives’ names. Fathers also desired their married daughters to have property rights to protect them (and their paternal inheritances) from financially irresponsible husbands. Such motives prompted legislatures in three states — Mississippi, Maine, and Massachusetts — to enact married women’s property laws between 1839 and 1845. Then, women activists in New York won a comprehensive statute that became the model for fourteen other states. The New York statute of 1848 gave women full legal control over the property they brought to a marriage.

Also in 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized a gathering of women’s rights activists in the small New York town of Seneca Falls. Seventy women and thirty men attended the Seneca Falls Convention, which issued a rousing manifesto extending to women the egalitarian republican ideology of the Declaration of Independence. “All men and women are created equal,” the Declaration of Sentiments declared, “[yet] the history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman [and] the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.” To persuade Americans to right this long-standing wrong, the activists resolved to “employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and National legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press on our behalf.” By staking out claims for equality for women in public life, the Seneca Falls reformers repudiated both the natural inferiority of women and the ideology of separate spheres.

Most men dismissed the Seneca Falls declaration as nonsense, and many women also rejected the activists and their message. In her diary, one small-town mother and housewife lashed out at the female reformer who “aping mannish manners … wears absurd and barbarous attire, who talks of her wrongs in harsh tone, who struts and strides, and thinks that she proves herself superior to the rest of her sex.”

Still, the women’s rights movement grew in strength and purpose. In 1850, delegates to the first national women’s rights convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, hammered out a program of action. The women called on churches to eliminate notions of female inferiority in their theology. Addressing state legislatures, they proposed laws to allow married women to institute lawsuits, testify in court, and assume custody of their children in the event of divorce or a husband’s death. Finally, they began a concerted campaign to win the vote for women. As delegates to the 1851 convention proclaimed, suffrage was “the corner-stone of this enterprise, since we do not seek to protect woman, but rather to place her in a position to protect herself.”

The activists’ legislative campaign required talented organizers and lobbyists. The most prominent political operative was Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906), a Quaker who had acquired political skills in the temperance and antislavery movements. Those experiences, Anthony reflected, taught her “the great evil of woman’s utter dependence on man.” Joining the women’s rights movement, she worked closely with Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Anthony created an activist network of political “captains,” all women, who relentlessly lobbied state legislatures. In 1860, her efforts secured a New York law granting women the right to control their own wages (which fathers or husbands had previously managed); to own property acquired by “trade, business, labors, or services”; and, if widowed, to assume sole guardianship of their children. Genuine individualism for women, the dream of transcendentalist Margaret Fuller, had advanced a tiny step closer to reality. In such small and much larger ways, the midcentury reform movements had altered the character of American culture.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What was the relationship between the abolitionist and women’s rights movements?