America’s History: Printed Page 349

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 319

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 310

The Utopian Impulse

Many rural communalists were farmers and artisans seeking refuge from the economic depression of 1837–1843. Others were religious idealists. Whatever their origins, these rural utopias were symbols of social protest and experimentation. By advocating the common ownership of property (socialism) and unconventional forms of marriage and family life, the communalists challenged traditional property rights and gender roles.

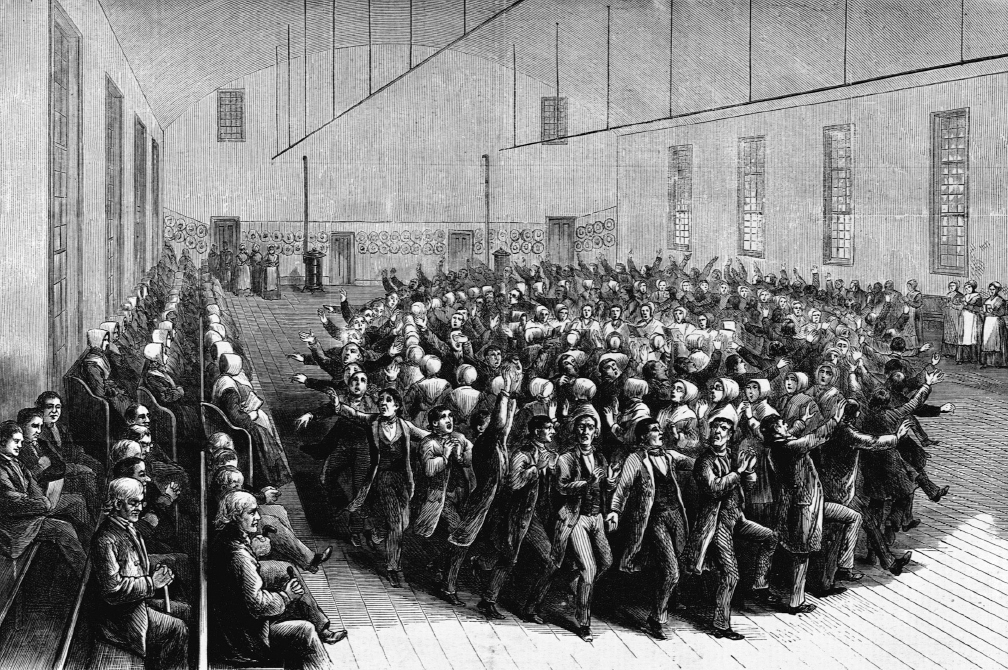

Mother Ann and the Shakers The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, known as the Shakers because of the ecstatic dances that were part of their worship, was the first successful American communal movement. In 1770, Ann Lee Stanley (Mother Ann), a young cook in Manchester, England, had a vision that she was an incarnation of Christ. Four years later, she led a few followers to America and established a church near Albany, New York.

After Mother Ann’s death in 1784, the Shakers honored her as the Second Coming of Christ, withdrew from the profane world, and formed disciplined religious communities. Members embraced the common ownership of property; accepted strict oversight by church leaders; and pledged to abstain from alcohol, tobacco, politics, and war. Shakers also repudiated sexual pleasure and marriage. Their commitment to celibacy followed Mother Ann’s testimony against “the lustful gratifications of the flesh as the source and foundation of human corruption.” The Shakers’ theology was as radical as their social thought. They held that God was “a dual person, male and female.” This doctrine prompted Shakers to repudiate male leadership and to place community governance in the hands of both women and men — the Eldresses and the Elders.

Shakers founded twenty communities, mostly in New England, New York, and Ohio. Their agriculture and crafts, especially furniture making, acquired a reputation for quality that made most Shaker communities self-sustaining and even comfortable. Because the Shakers disdained sexual intercourse, they relied on conversions and the adoption of thousands of young orphans to increase their numbers. During the 1830s, three thousand adults, mostly women, joined the Shakers, attracted by their communal intimacy and sexual equality. To Rebecca Cox Jackson, an African American seamstress from Philadelphia, the Shakers seemed to be “loving to live forever.” However, with the proliferation of public and private orphanages during the 1840s and 1850s, Shaker communities began to decline and, by 1900, had virtually disappeared. They left as a material legacy a plain but elegant style of wood furniture.

Albert Brisbane and Fourierism As the Shakers’ growth slowed during the 1840s, the American Fourierist movement mushroomed. Charles Fourier (1777–1837) was a French reformer who devised an eight-stage theory of social evolution that predicted the imminent decline of individual property rights and capitalist values. Fourier’s leading disciple in America was Albert Brisbane. Just as republicanism had freed Americans from slavish monarchical government, Brisbane argued, so Fourierist socialism would liberate workers from capitalist employers and the “menial and slavish system of Hired Labor or Labor for Wages.” Members would work for the community, in cooperative groups called phalanxes; they would own its property in common, including stores and a bank, a school, and a library.

Fourier and Brisbane saw the phalanx as a humane system that would liberate women as well as men. “In society as it is now constituted,” Brisbane wrote, individual freedom was possible only for men, while “woman is subjected to unremitting and slavish domestic duties.” In the “new Social Order … based upon Associated households,” men would share women’s domestic labor and thereby increase sexual equality.

Brisbane skillfully promoted Fourier’s ideas in his influential book The Social Destiny of Man (1840), a regular column in Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, and hundreds of lectures. Fourierist ideas found a receptive audience among educated farmers and craftsmen, who yearned for economic stability and communal solidarity following the Panic of 1837. During the 1840s, Fourierists started nearly one hundred cooperative communities, mostly in western New York and the Midwest. Most communities quickly collapsed as members fought over work responsibilities and social policies. Fourierism’s rapid decline revealed the difficulty of maintaining a utopian community in the absence of a charismatic leader or a compelling religious vision.

John Humphrey Noyes and Oneida John Humphrey Noyes (1811–1886) was both charismatic and religious. He ascribed the Fourierists’ failure to their secular outlook and embraced the pious Shakers as the true “pioneers of modern Socialism.” The Shakers’ marriageless society also inspired Noyes to create a community that defined sexuality and gender roles in radically new ways.

Noyes was a well-to-do graduate of Dartmouth College who joined the ministry after hearing a sermon by Charles Grandison Finney. Dismissed as the pastor of a Congregational church for holding unorthodox beliefs, Noyes turned to perfectionism, an evangelical Protestant movement of the 1830s that attracted thousands of New Englanders who had migrated to New York and Ohio. Perfectionists believed that Christ had already returned to earth (the Second Coming) and therefore people could aspire to sinless perfection in their earthly lives. Unlike most perfectionists, who lived conventional personal lives, Noyes rejected marriage, calling it a major barrier to perfection. “Exclusiveness, jealousy, quarreling have no place at the marriage supper of the Lamb,” Noyes wrote. Instead of the Shakers’ celibacy, Noyes embraced “complex marriage,” in which all members of the community were married to one another. He rejected monogamy partly to free women from their status as the property of their husbands, as they were by custom and by common law. Symbolizing the quest for equality, Noyes’s women followers cut their hair short and wore pantaloons under calf-length skirts.

In 1839, Noyes set up a perfectionist community near his hometown of Putney, Vermont. However, local outrage over the practice of complex marriage forced Noyes to relocate the community in 1848 to an isolated area near Oneida, New York, where the members could follow his precepts. To give women the time and energy to participate fully in community affairs, Noyes urged them to avoid multiple pregnancies. He asked men to help by avoiding orgasm during intercourse. Less positively, he encouraged sexual relations at a very early age and used his position of power to manipulate the sexual lives of his followers.

By the mid-1850s, the Oneida settlement had two hundred residents and became self-sustaining when the inventor of a highly successful steel animal trap joined the community. With the profits from trap making, the Oneidians diversified into the production of silverware. When Noyes fled to Canada in 1879 to avoid prosecution for adultery, the community abandoned complex marriage but retained its cooperative spirit. The Oneida Community, Ltd., a jointly owned silverware-manufacturing company, remained a successful communal venture until the middle of the twentieth century.

The historical significance of the Oneidians, Shakers, and Fourierists does not lie in their numbers, which were small, or in their fine crafts. Rather, it stems from their radical questioning of traditional sexual norms and of the capitalist values and class divisions of the emerging market society. Their utopian communities stood as countercultural blueprints of a more egalitarian social and economic order.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What factors led to the proliferation of rural utopian communities in nineteenth-century America?