America’s History: Printed Page 398

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

Childhood in Black and White

A major theme of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s powerful antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin is the sin of separating black families and denying parental rights to enslaved mothers and fathers. The following documents reveal the dynamics of plantation family life, and particularly mother-child relations.

Ex-slave Josephine Smith, interviewed at age ninety-four by Mary A. Hicks, Raleigh, North Carolina, 1930s. Slave children had loving but limited relationships with their mothers, who worked long hours in the fields and were sometimes sold away from their children.

I ‘members seein’ a heap o’ slave sales, wid de niggers in chains, an’ de spec’ulators sellin’ an’ buyin’ dem off. I also ‘members seein’ a drove of slaves wid nothin’ on but a rag ‘twixt dere legs bein’ galloped roun’ ‘fore de buyers. ‘Bout de wust thing dat eber I seed do’ wuz a slave ‘woman at Louisburg who had been sold off from her three weeks old baby, an wuz bein’ marched ter New Orleans.

She had walked till she quz give out, an’ she wuz weak enough ter fall in de middle o’ de road. … As I pass by dis ‘oman begs me in God’s name fer a drink o’ water, an’ I gives it ter her. I ain’t neber be so sorry fer nobody. …Dey walk fer a little piece an’ dis ‘oman fall out. She dies dar side o’ de road, an’ right dar dey buries her, cussin’, dey tells me, ’bout losin’ money on her.

“Narrative of James Curry, a Fugitive Slave,” The Liberator, January 10, 1840. The abolitionist newspaper The Liberator published heartrending accounts of death and separation in slave families and how “fictive kinship” assisted the survivors.

My mother’s labor was very hard. She would go to the house in the morning, take her pail upon her head, and go away to the cow-pen, and milk fourteen cows. She then put on the bread for the family breakfast, and got the cream ready for churning, and set a little child to churn it, she having the care of from ten to fifteen children, whose mothers worked in the field. …Among the slave children, were three little orphans, whose mothers, at their death, committed them to the care of my mother. One of them was a babe. She took them and treated them as her own. The master took no care about them. She always took a share of the cloth she had provided for her own children, to cover these little friendless ones.

Former slave Barney Alford, interview for the Works Progress Administration in Mississippi, 1930s.

Ole mammy ‘Lit’ wus mity ole en she lived in one corner of de big yard en she keered fur all de black chilluns while de old folks wurk in de field. Mammy Lit wus good to all de chilluns en I had ter help her wid dem chilluns en keep dem babies on de pallet. Mammy Lit smoked a pipe, en sum times I wuld hide dat pipe, en she wuld slap me fur it, den sum times I wuld run way en go ter de kitchen whar my mammy wus at wurk en mammy Lit wuld hafter cum fur me en den she wuld whip me er gin. She sed I wus bad.

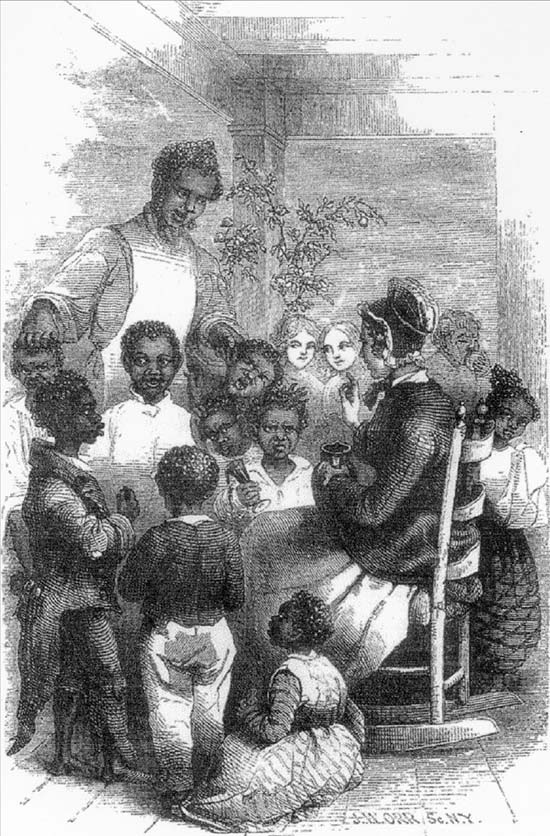

“Mrs. Meriwether Administering Bitters,” illustration from John Pendleton Kennedy, Swallow Barn, Or, A Sojourn in the Old Dominion, 1851. Bitters — strong alcoholic beverages flavored with bitter herbs — were administered as medicine in the nineteenth century, as in this depiction of a planter’s wife tending to enslaved children. Kennedy’s cheerful depictions of Virginia plantation life in this popular book, first published in 1832, reinforced the notion of slavery as a “positive good.”

Source: Picture Research Consultants & Archives.

Source: Picture Research Consultants & Archives.G. M. J., “Early Culture of Children,” 1855. This excerpt from a Christian advice manual for mothers reflects the values of the mid-nineteenth-century white Protestant middle class.

“Train up a child in the way he should go,” is a law as imperative in the 19th century, as when first uttered by the lips of the wise man. Mothers are the natural executors of this law to their daughters. Nothing but the most unavoidable and pressing force of circumstances, should wrench this power from their hands. Who will guard with a mother’s jealous eye the health, habits, morals, and religion of this most delicate part of creation. … How often I have been pained to see mothers place those delicate plants in the nursery with servants, whose tastes, feelings, morals, manners, and language are but a little removed from the lower animals of creation; there to receive impressions, and imbibe habits, which will grow with their growth, and strengthen with their strength, until like the branches of the giant oak, they shall expand and deepen into a shade that will forever conceal the parent stock.

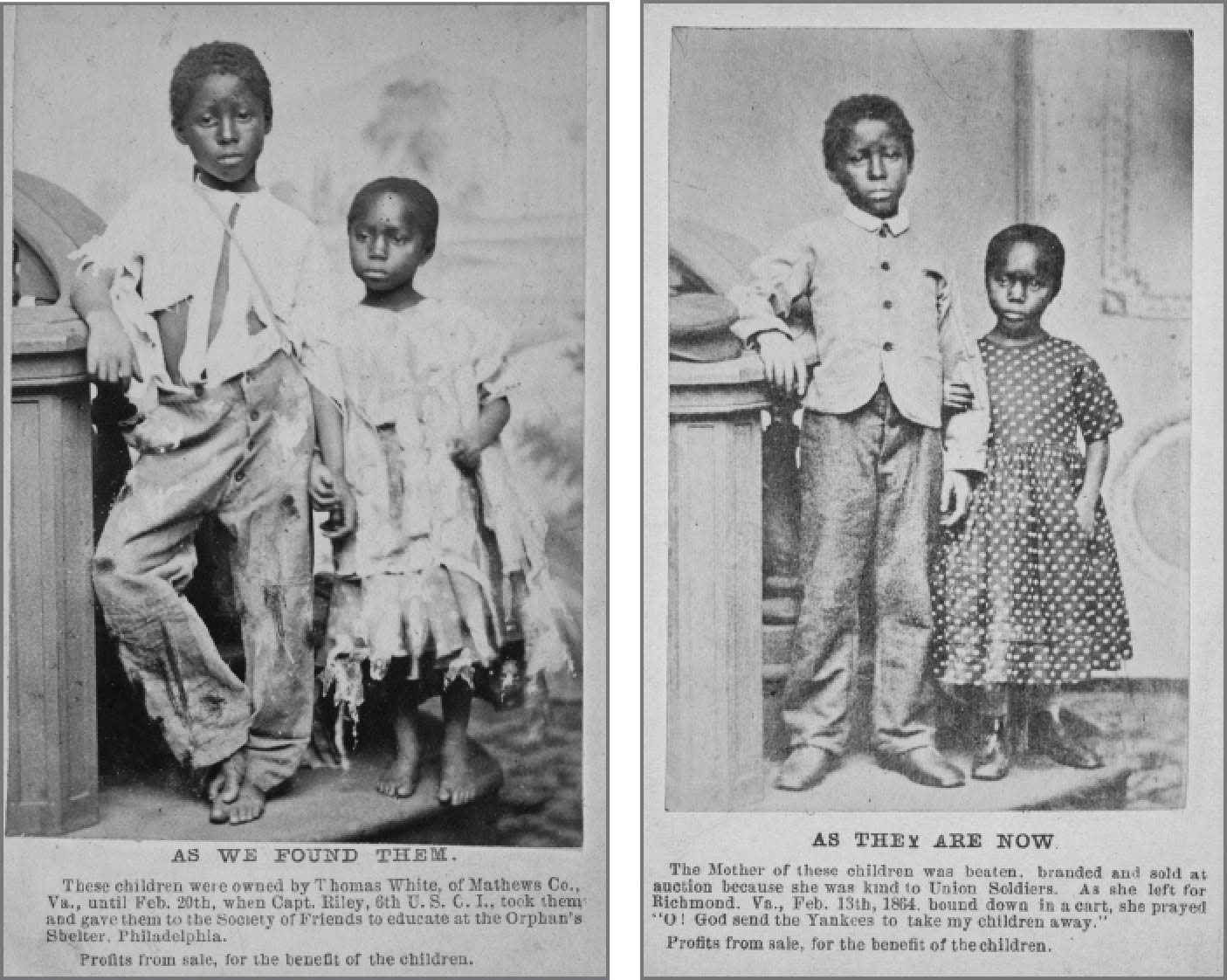

Visiting Cards Created by Philadelphia Portrait Painter and Photographer Peregrine F. Cooper, As We Found Them (left), As They Are Now (right), 1864. One of the ways to “train up a child in the way he should go” was to inculcate abolitionist sentiments early and often.

Source: George Eastman House.

Source: George Eastman House.

Sources: (1) WPA Slave Narrative Project, 1936–38, learnnc.org; (2) “Narrative of James Curry, a Fugitive Slave,” The Liberator, January 10, 1840, learnnc.org; (3) The MS Gen Web Project, msgw.org/slaves/alford-xslave.htm; (5) Home Garner; or the Intellectual and Moral Store House, ed. Mary G. Clarke (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott & Co., 1855), 115.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

What do these sources reveal about slave communities? About the extent to which the ideology of “benevolent paternalism” governed the behavior of slave owners?

Question

How does the engraving (source 4) compare to the descriptions of the care of slave children (sources 1–3)? What biases, if any, can you detect in these sources?

Question

How would a person holding the beliefs described in source 5 react to the engraving of Mrs. Meriwether? To images showing slave “mammies” raising the master’s children?

Question

How do the images of enslaved children in source 6 pertain to “train[ing] up a child in the way he should go”? How effective are they? What emotions do they play upon?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

In the political system, debate over “the peculiar institution” of slavery often focused on property rights and constitutional principles. In the actual world of the plantation, human bondage evoked a range of human emotions — jealousy, resentment, anger, love, fear, tenderness — and human pain. Write an essay that assesses the economic, legal, and political arguments over slavery in light of the experiences of enslaved mothers and children.