America’s History: Printed Page 401

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 366

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 355

The Free Black Population

Some African Americans escaped slavery through flight or a grant of freedom by their owners and, if they lived in the North, through gradual emancipation laws that, by 1840, had virtually ended bound labor. The proportion of free blacks rose from 8 percent of the African American population in 1790 to about 13 percent between 1820 and 1840, and then (because of high birthrates among enslaved blacks) fell to 11 percent. Still, the number of free blacks continued to grow. In the slave state of Maryland in 1860, half of all African Americans were free, and many more were “term” slaves, guaranteed their freedom in exchange for a few more years of work.

Northern Blacks Almost half of free blacks in the United States in 1840 (some 170,000) and again in 1860 (250,000) lived in the free states of the North. However, few of them enjoyed unfettered freedom. Most whites regarded African Americans as their social inferiors and confined them to low-paying jobs. In rural areas, blacks worked as farm laborers or tenant farmers; in towns and cities, they toiled as domestic servants, laundresses, or day laborers. Only a small number of African Americans owned land. “You do not see one out of a hundred … that can make a comfortable living, own a cow, or a horse,” a traveler in New Jersey noted. In most states, law or custom prohibited northern blacks from voting, attending public schools, or sitting next to whites in churches. They could testify in court against whites only in Massachusetts. The federal government did not allow African Americans to work for the postal service, claim public lands, or hold a U.S. passport. As black activist Martin Delaney remarked in 1852: “We are slaves in the midst of freedom.”

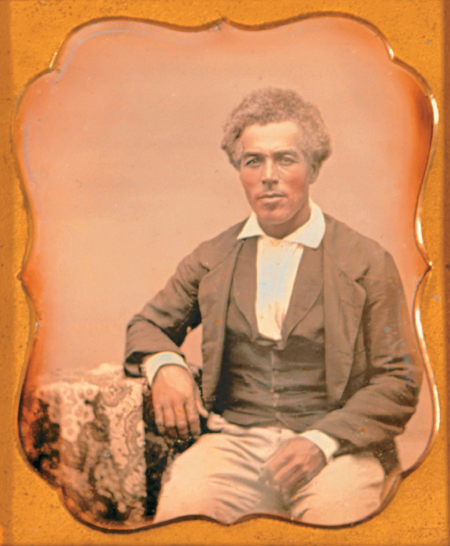

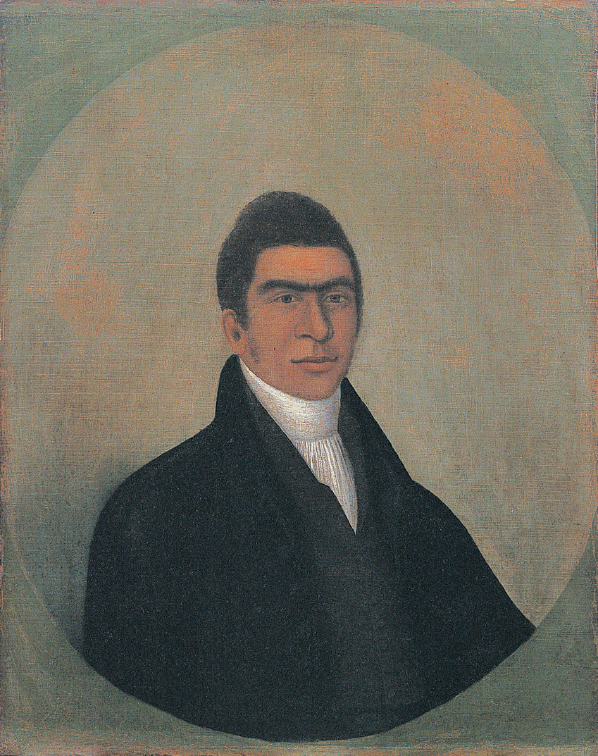

Of the few African Americans able to make full use of their talents, several achieved great distinction. Mathematician and surveyor Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806) published an almanac and helped lay out the new capital in the District of Columbia; Joshua Johnston (1765–1832) won praise for his portraiture; and merchant Paul Cuffee (1759–1817) acquired a small fortune from his business enterprises. More impressive and enduring were the community institutions created by free African Americans. Throughout the North, these largely unknown men and women founded schools, mutual-benefit organizations, and fellowship groups, often called Free African Societies. Discriminated against by white Protestants, they formed their own congregations and a new religious denomination — the African Methodist Episcopal Church, headed by Bishop Richard Allen.

These institutions gave African Americans a measure of cultural autonomy, even as they marked sharp social divisions among blacks. “Respectable” blacks tried through their dress, conduct, and attitude to win the “esteem and patronage” of prominent whites — first Federalists and then Whigs and abolitionists — who were sympathetic to their cause. Those efforts separated them from impoverished blacks, who distrusted not only whites but also blacks who “acted white.”

Standing for Freedom in the South The free black population in the slave states numbered approximately 94,000 in 1810 and 225,000 in 1860. Most of these men and women lived in coastal cities — Mobile, Memphis, New Orleans — and in the Upper South. Partly because skilled Europeans avoided the South, free blacks formed the backbone of the urban artisan workforce. African American carpenters, blacksmiths, barbers, butchers, and shopkeepers played prominent roles in the economies of Baltimore, Richmond, Charleston, and New Orleans. But whatever their skills, free blacks faced many dangers. White officials often denied jury trials to free blacks accused of crimes, and sometimes they forced those charged with vagrancy back into slavery. Some free blacks were simply kidnapped and sold.

As a privileged minority among African Americans in the South, free blacks had divided loyalties. To advance the welfare of their families, some distanced themselves from plantation slaves and assimilated white culture and values. Indeed, mixed-race individuals sometimes joined the ranks of the planter class. David Barland, one of twelve children born to a white Mississippi planter and his black slave Elizabeth, himself owned no fewer than eighteen slaves. In neighboring Louisiana, some free blacks supported secession because they owned slaves and were “dearly attached to their native land.”

Such individuals were exceptions. Most free African Americans acknowledged their ties to the great mass of slaves, some of whom were their relatives. “We’s different [from whites] in color, in talk and in ’ligion and beliefs,” said one. Calls by white planters in the 1840s to re-enslave free African Americans reinforced black unity. Knowing their own liberty was not secure so long as slavery existed, free blacks celebrated on August 1, the day slaves in the British West Indies won emancipation, and sought a similar goal for enslaved African Americans. As a delegate to the National Convention of Colored People in 1848 put it, “Our souls are yet dark under the pall of slavery.” In the rigid American caste system, free blacks stood as symbols of hope to enslaved African Americans and as symbols of danger to most whites.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How were the lives of free African Americans different in the northern and southern states?