America’s History: Printed Page 378

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 345

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 334

The Domestic Slave Trade

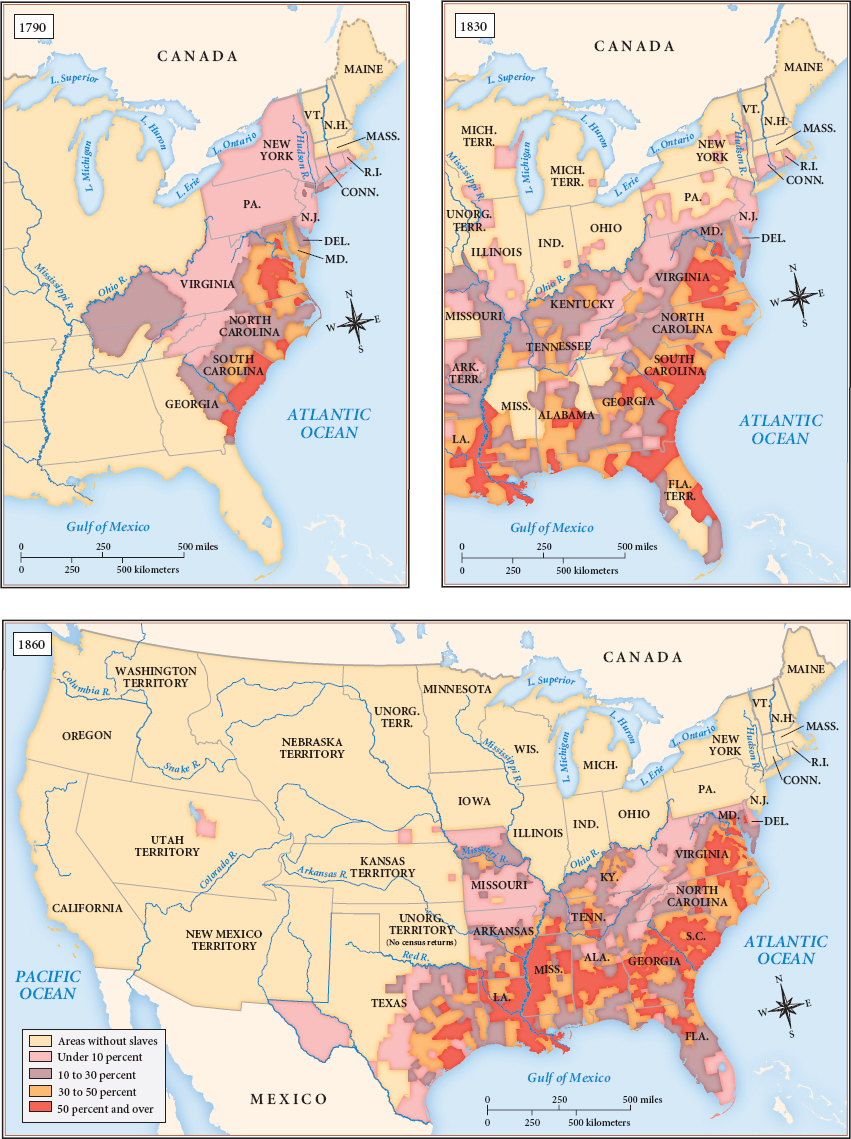

In 1817, when the American Colonization Society began to transport a few freed blacks to Africa, the southern plantation system was expanding rapidly. In 1790, its western boundary ran through the middle of Georgia; by 1830, it stretched through western Louisiana; by 1860, the slave frontier extended far into Texas (Map 12.1). That advance of 900 miles more than doubled the geographical area cultivated by slave labor and increased the number of slave states from eight in 1800 to fifteen by 1850. The federal government played a key role in this expansion. It acquired Louisiana from the French in 1803, welcomed the slave states of Mississippi and Alabama into the Union in 1817 and 1819, removed Native Americans from the southeastern states in the 1830s, and annexed Texas and Mexican lands in the 1840s.

To cultivate this vast area, white planters imported enslaved laborers first from Africa and then from the Chesapeake region. Between 1776 and 1809, when Congress outlawed the Atlantic slave trade, planters purchased about 115,000 Africans. “The Planter will … Sacrifice every thing to attain Negroes,” declared one slave trader. Despite the influx, the demand for labor far exceeded the supply. Consequently, planters imported new African workers illegally, through the Spanish colony of Florida until 1819 and then through the Mexican province of Texas. Yet these Africans — about 50,000 between 1810 and 1865 — did not satisfy the demand.