America’s History: Printed Page 384

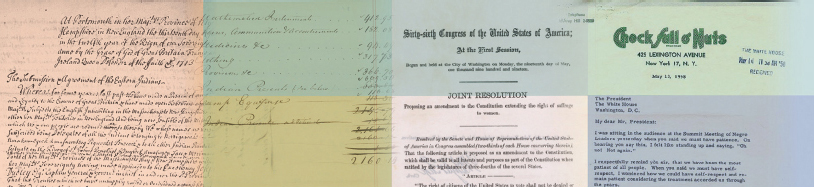

AMERICAN VOICES |  |

The Debate over Free and Slave Labor

As the abolitionist assault on slavery mounted, its rhetoric shaped the debate over the emergent system of wage labor in the northern states. By the 1850s, New York senator William Seward starkly contrasted the political systems of the South and the North in terms of their labor systems: “the one resting on the basis of servile or slave labor, the other on voluntary labor of freemen.” Seward strongly favored the “free-labor system,” crediting to it “the strength, wealth, greatness, intelligence, and freedom, which the whole American people now enjoy.” As the following documents show, some Americans agreed with Seward, while others, such as New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley and South Carolina senator James Henry Hammond (who is quoted often in this chapter and whose house appears on page 383), contested his premises and conclusions.

South Carolina Senator James Henry Hammond

Speech to the Senate, March 4, 1858

In response to New York senator Seward, Senator Hammond urged admission of Kansas under the proslavery Lecompton Constitution and, by way of argument, celebrated the success of the South’s cotton economy and its political and social institutions.

In all social systems there must be a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life. …Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization, and refinement. It constitutes the very mud-sill of society and of political government. …Fortunately for the South, she found a race adapted to that purpose to her hand. A race inferior to her own, but eminently qualified in temper, in vigor, in docility, in capacity to stand the climate, to answer all her purposes. We use them for our purpose, and call them slaves. …

The Senator from New York said yesterday that the whole world had abolished slavery. Aye, the name, but not the thing; …for the man who lives by daily labor, and scarcely lives at that, and who has to put out his labor in the market, and take the best he can get for it; in short, your whole hireling class of manual laborers and “operatives,” as you call them, are essentially slaves. The difference between us is, that our slaves are hired for life and well compensated; there is no starvation, no begging, no want of employment among our people, and not too much employment either. Yours are hired by the day, not cared for, and scantily compensated, which may be proved in the most painful manner, at any hour in any street in any of your large towns.

Source: The Congressional Globe (Washington, DC, March 6, 1858), 962.

New York Protestant Episcopal Church Mission Society

Sixth Annual Report, 1837

This excerpt demonstrates the society’s belief that a class-bound social order could be avoided by encouraging “a spirit of independence and self-estimation” among the poor.

In the older countries of Europe, there is a CLASS OF POOR: families born to poverty, living in poverty, dying in poverty. With us there are none such. In our bounteous land individuals alone are poor; but they form no poor class, because with them poverty is but a transient evil… save [except] paupers and vagabonds … all else form one common class of citizens; some more, others less advanced in the career of honorable independence.

Source: New York Protestant Episcopal Church Mission Society, Sixth Annual Report (New York, 1837), 15–16.

Horace Greeley

Public Letter Declining an Invitation to Attend an Antislavery Convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, June 3, 1845

This letter from the editor of the New York Tribune explains his broad definition of slavery.

Dear Sir: — I received, weeks since, your letter inviting me to be present at a general convention of opponents of Human Slavery. …What is Slavery? You will probably answer; “The legal subjection of one human being to the will and power of another.” But this definition appears to me inaccurate. …

I understand by Slavery, that condition in which one human being exists mainly as a convenience for other human beings. …In short, …where the relation [is one] of authority, social ascendency and power over subsistence on the one hand, and of necessity, servility, and degradation on the other — there, in my view, is Slavery… If I am less troubled concerning the Slavery prevalent in Charleston or New-Orleans, it is because I see so much Slavery in New-York. …

Wherever Opportunity to Labor is obtained with difficulty, and is so deficient that the Employing class may virtually prescribe their own terms and pay the Laborer only such share as they choose of the produce, there is a strong tendency to Slavery.

Source: Horace Greeley, Hints Toward Reform in Lectures, Addresses, and Other Writings (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1850), 352–355.

Editorial in the Staunton Spectator, 1859

Entitled “Freedom and Slavery,” this editorial argues that “the black man’s lot as a slave, is vastly preferable to that of his free brethren at the North.”

The intelligent, christian slave-holder at the South is the best friend of the negro. He does not regard his bonds-men as mere chattel property, but as human beings to whom he owes duties. While the Northern Pharisee will not permit a negro to ride on the city railroads, Southern gentlemen and ladies are seen every day, side by side, in cars and coaches, with their faithful servants. Here the honest black man is not only protected by the laws and public sentiment, but he is respected by the community as truly as if his skin were white. Here there are ties of genuine friendship and affection between whites and blacks, leading to an interchange of all the comities of life. The slave nurses his master in sickness, and sheds tears of genuine sorrow at his grave.

Source: Staunton Spectator, December 6, 1859, p. 2, c. 1.

James Henry Hammond

Private Letter to His Son Harry Hammond, 1856

This letter regards the future of Hammond’s slave mistress, Sally Johnson, her son Henderson, and her daughter Louisa, who was the common mistress of father and son, and Louisa’s children whom they sired.

In the last will I made I left to you … Sally Johnson the mother of Louisa & all the children of both. Sally says Henderson is my child. It is possible, but I do not believe it Yet act on her’s rather than my opinion. Louisa’s first child may be mine. I think not. Her second I believe is mine. Take care of her & her children who are both of your blood if not of mine. …The services of the rest will compensate for indulgence to these. I cannot free these people & send them North. It would be cruelty to them. Nor would I like that any but my own blood should own as slaves my own blood or Louisa. I leave them to your charge, believing that you will best appreciate & most independently carry out my wishes in regard to them. Do not let Louisa or any of my children or possible children be the Slaves of Strangers. Slavery in the family will be their happiest earthly condition.

Source: James Hammond to Harry Hammond, February 19, 1856, in JHH Papers, SCL, quoted in Drew Gilpin Faust, James Henry Hammond and the Old South: A Design for Mastery (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982), 87.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Question

Which of these documents argue for slave owners as benevolent paternalists and the institution of slavery as a “positive good”? What other points of view are represented?

Question

Given the discussion of “class” and “honorable independence” in the Mission Society statement, how would an Episcopalian reply to Hammond’s critique of the northern labor system?

Question

How can we understand Hammond’s treatment of Sally Johnson and her daughter, as well as his refusal to free his and his son’s children, in the context of his 1858 speech and the Staunton Spectator’s editorial?

Question

Using the principles asserted in his letter, how would Horace Greeley analyze the southern labor system, as described by Hammond and the Staunton Spectator? Why does Greeley suggest that the northern system has only “a strong tendency to Slavery”?

Question

Consider the sources above in the light of this Abraham Lincoln comment: “although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it, by being a slave himself.”