America’s History: Printed Page 421

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 385

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 374

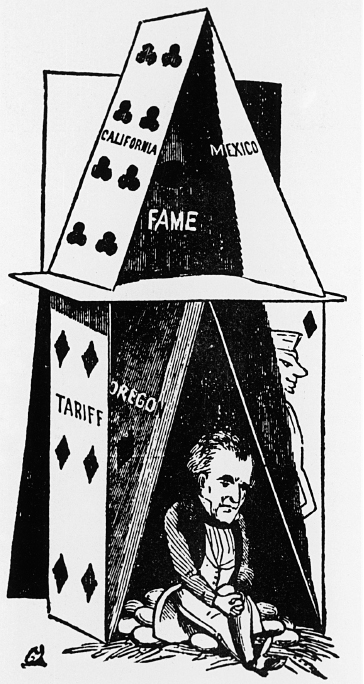

A Divisive Victory

Initially, the war with Mexico sparked an explosion of patriotic expansionism. The Nashville Union hailed it as a noble struggle to extend “the principles of free government.” However, the war soon divided the nation (American Voices). Some northern Whigs — among them Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts (the son of John Quincy Adams) and Chancellor James Kent of New York — opposed the war on moral grounds, calling it “causeless & wicked & unjust.” Adams, Kent, and other conscience Whigs accused Polk of waging a war of conquest to add new slave states and give slave-owning Democrats permanent control of the federal government. Swayed by such arguments, troops deserted in droves (creating the highest desertion rate of any American war), and antiwar activists denounced enlistees as “murderers and robbers.” “The United States will conquer Mexico,” Ralph Waldo Emerson had predicted as the war began, but “Mexico will poison us.”

When voters repudiated Polk’s war policy in the elections of 1846, the Whig Party took control of Congress. Whig leaders called for “No Territory” — a congressional pledge that the United States would not seek any land from the Mexican republic. “Away with this wretched cant about a ‘manifest destiny,’ a ‘divine mission’ … to civilize, and Christianize, and democratize our sister republics at the mouth of a cannon,” declared New York senator William Duer.

The Wilmot Proviso Polk’s expansionist policies also split the Democrats. As early as 1839, Ohio Democrat Thomas Morris had warned that “the power of slavery is aiming to govern the country, its Constitutions and laws.” In 1846, David Wilmot, an antislavery Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania, took up that refrain and proposed the so-called Wilmot Proviso, a ban on slavery in any territories gained from the war. Whigs and antislavery Democrats in the House of Representatives quickly passed the bill, dividing Congress along sectional lines. “The madmen of the North … ,” grumbled the Richmond Enquirer, “have, we fear, cast the die and numbered the days of this glorious Union.” Fearing that outcome, a few proslavery northern senators joined their southern colleagues to kill the proviso.

Fervent Democratic expansionists now became even more aggressive. President Polk, Secretary of State Buchanan, and Senators Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and Jefferson Davis of Mississippi called for the annexation of a huge swath of Mexican territory south of the Rio Grande. However, John C. Calhoun and other southern whites feared this demand would extend the costly war and require the assimilation of many dark-skinned mestizos. They favored only the annexation of sparsely settled New Mexico and California. “Ours is a government of the white man,” proclaimed Calhoun, which should never welcome “into the Union any but the Caucasian race.” To unify the Democratic Party, Polk and Buchanan accepted Calhoun’s policy. In 1848, Polk signed, and the Senate ratified, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which the United States agreed to pay Mexico $15 million in return for more than one-third of its territory (Map 13.4).

Congress also created the Oregon Territory in 1848 and, two years later, passed the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act, which granted farm-sized plots of “free land” to settlers who took up residence before 1854. Soon, treaties with native peoples extinguished Indian titles to much of the new territory. With the settlement of Oregon and the acquisition of New Mexico and California, the American conquest of the Far West was far advanced.

Free Soil However, the political debate over expansion was far from over and dominated the election of 1848. The Senate’s rejection of the Wilmot Proviso revived Thomas Morris’s charge that leading southerners were part of a “Slave Power” conspiracy to dominate national life. To thwart any such plan, thousands of ordinary northerners, including farmer Abijah Beckwith of Herkimer County, New York, joined the free-soil movement. Slavery, Beckwith wrote in his diary, was an institution of “aristocratic men” and a danger to “the great mass of the people [because it] … threatens the general and equal distribution of our lands into convenient family farms.”

The free-soilers quickly organized the Free-Soil Party in 1848. The new party abandoned the Garrisonians’ and Liberty Party’s emphasis on the sinfulness of slavery and the natural rights of African Americans. Instead, like Beckwith, it depicted slavery as a threat to republicanism and to the Jeffersonian ideal of a freeholder society, arguments that won broad support among aspiring white farmers. Hundreds of men and women in the Great Lakes states joined the free-soil organizations formed by the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. So, too, did Frederick Douglass, the foremost black abolitionist, who attended the first Free-Soil Party convention in the summer of 1848 and endorsed its strategy. However, William Lloyd Garrison and other radical abolitionists condemned the Free-Soilers’ stress on white freehold farming as racist “whitemanism.”

The Election of 1848 The conflict over slavery took a toll on Polk and the Democratic Party. Scorned by Whigs and Free-Soilers and exhausted by his rigorous dawn-to-midnight work regime, Polk declined to run for a second term and died just three months after leaving office. In his place, the Democrats nominated Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan, an avid expansionist who had advocated buying Cuba, annexing Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, and taking all of Oregon. To maintain party unity on the slavery issue, Cass promoted a new idea, squatter sovereignty. Under this plan, Congress would allow settlers in each territory to determine its status as free or slave.

Cass’s doctrine of squatter sovereignty failed to persuade those northern Democrats who opposed any expansion of slavery. They joined the Free-Soil Party, as did former Democratic president Martin Van Buren, who became its candidate for president. To attract Whig votes, the Free-Soilers chose conscience Whig Charles Francis Adams for vice president.

The Whigs nominated General Zachary Taylor. Taylor was a Louisiana slave owner firmly committed to the defense of slavery in the South but not in the territories, a position that won him support in the North. Moreover, the general’s military exploits had made him a popular hero, known affectionately among his troops as “Old Rough and Ready.” In 1848, as in 1840 with the candidacy of William Henry Harrison, running a military hero worked for the Whigs. Taylor took 47 percent of the popular vote to Cass’s 42 percent. However, Taylor won a majority in the electoral college (163 to 127) only because Van Buren and the Free-Soil ticket took enough votes in New York to deny Cass a victory there. Although their numbers were small, antislavery voters in New York had denied the presidency to Clay in 1844 and to Cass in 1848. The bitter debate over slavery had changed the dynamics of national politics.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What did conscience Whigs, David Wilmot, and free-soilers have in common, and why did they all rise to prominence between 1846 and 1848?