America’s History: Printed Page 425

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 389

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 376

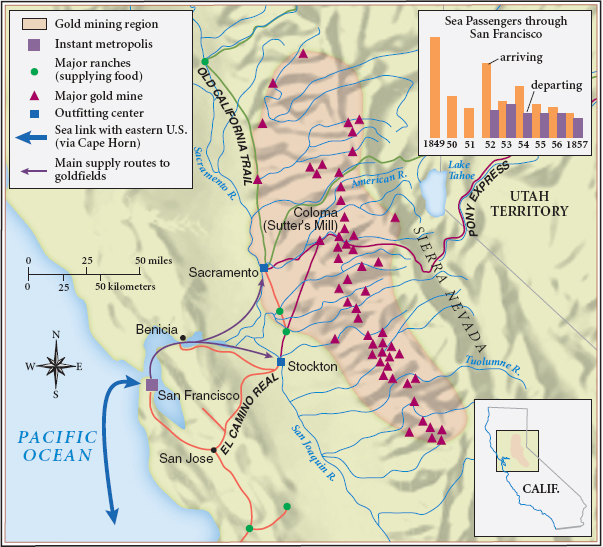

California Gold and Racial Warfare

Even before Taylor took office, events in sparsely settled California took center stage. In January 1848, workers building a milldam for John A. Sutter in the Sierra Nevada foothills came across flakes of gold. Sutter was a Swiss immigrant who came to California in 1839, became a Mexican citizen, and accumulated land in the Sacramento River Valley. He tried to hide the discovery, but by mid-1848 Americans from Monterey and San Francisco were pouring into the foothills, along with hundreds of Indians and Californios and scores of Australians, Mexicans, and Chileans. The gold rush was on (America Compared). By January 1849, sixty-one crowded ships had left New York and other northeastern ports to sail around Cape Horn to San Francisco; by May, twelve thousand wagons had crossed the Missouri River bound for the goldfields (Map 13.5). For Bernard Reid, the overland trip on the Pioneer Line was “a long dreadful dream,” beset by cholera, scurvy, and near starvation. Still, by the end of 1849, more than 80,000 people, mostly men — the so-called forty-niners — had arrived in California.

The Forty-Niners The forty-niners lived in crowded, chaotic towns and mining camps amid gamblers, saloon keepers, and prostitutes. They set up “claims clubs” to settle mining disputes and cobbled together a system of legal rules based on practice “back East.” The American miners usually treated alien whites fairly but ruthlessly expelled Indians, Mexicans, and Chileans from the goldfields or confined them to marginal diggings. When substantial numbers of Chinese miners arrived in 1850, often in the employ of Chinese companies, whites called for laws to expel them from California.

The first miners to exploit a site often struck it rich. They scooped up the easily reached deposits, leaving small pickings for later arrivals. His “high hopes” wrecked, one latecomer saw himself and most other forty-niners as little better than “convicts condemned to exile and hard labor.” They faced disease and death as well: “Diarrhea was so general during the fall and winter months” and so often fatal, a Sacramento doctor remarked, that it was called “the disease of California.” Like many migrants, William Swain gave up the search for gold in 1850 and borrowed funds to return to his wife, infant daughter, and aged mother on a New York farm. “O William,” his wife Sabrina had written, “I wish you had been content to stay at home, for there is no real home for me without you.”

Thousands of disillusioned forty-niners were either too ashamed or too tired or too ambitious to go home. Some became wageworkers for companies that engaged in hydraulic or underground mining; others turned to farming. “Instead of going to the mines where fortune hangs upon the merest chance,” a frustrated miner advised emigrants, “[you] should at once commence the cultivation of the soil.”

Racial Warfare and Land Rights Farming required arable land, and Mexican grantees and native peoples owned or claimed much of it. The American migrants brushed aside both groups, brutally eliminating the Indians and wearing down Mexican claimants with legal tactics and political pressure. The subjugation of the native peoples came first. When the gold rush began in 1848, there were about 150,000 Indians in California; by 1861, there were only 30,000. As elsewhere in the Americas, European diseases took the lives of thousands. In California, white settlers also undertook systematic campaigns of extermination, and local political leaders did little to stop them: “A war of extermination will continue to be waged … until the Indian race becomes extinct,” predicted Governor Peter Burnett in 1851. Congress abetted these assaults. At the bidding of white Californians, it repudiated treaties that federal agents had negotiated with 119 tribes and that had provided the Indians with 7 million acres of land. Instead, in 1853, Congress authorized five reservations of only 25,000 acres each and refused to provide the Indians with military protection.

Consequently, some settlers simply murdered Indians to push them off nonreservation lands. The Yuki people, who lived in the Round Valley in northern California, were one target. As the Petaluma Journal reported in April 1857: “Within the past three weeks, from 300 to 400 bucks, squaws and children have been killed by whites.” Other white Californians turned to slave trading: “Hundreds of Indians have been stolen and carried into the settlements and sold,” the state’s Indian Affairs superintendent reported in 1856. Labor-hungry farmers quickly put them to work. Indians were “all among us, around us, with no house and kitchen without them,” recalled one farmer. Expelled from their lands and widely dispersed, many Indian peoples simply vanished as distinct communities. Those tribal communities that survived were a shadow of their former selves. In 1854, at least 5,000 Yukis lived in the Round Valley; a decade later, only 85 men and 215 women remained.

The Mexicans and Californios who held grants to thousands of acres were harder to dislodge. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo guaranteed that the property owned by Mexicans would be “inviolably respected.” Although many of the 800 grants made by Spanish and Mexican authorities in California were either fraudulent or poorly documented, the Land Claims Commission created by Congress eventually upheld the validity of 75 percent of them. In the meantime, hundreds of Americans had set up farms on the sparsely settled grants. Having come of age in the antimonopoly Jacksonian era, these American squatters rejected the legitimacy of the Californios’ claims to unoccupied and unimproved land and successfully pressured local land commissioners and judges to void or reduce the size of many grants. Indeed, the Americans’ clamor for land was so intense and their numbers so large that many Californio claimants sold off their properties at bargain prices.

In northern California, farmers found that they could grow most eastern crops: corn and oats to feed work horses, pigs, and chickens; potatoes, beans, and peas for the farm table; and refreshing grapes, apples, and peaches. Ranchers gradually replaced Spanish cattle with American breeds that yielded more milk and meat, which found a ready market as California’s population shot up to 380,000 by 1860 and 560,000 by 1870. Most important, using the latest agricultural machinery and scores of hired workers, California farmers produced huge crops of wheat and barley, which San Francisco merchants exported to Europe at high prices. The gold rush turned into a wheat boom.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

What were the main changes caused by the huge increase in California’s population and its composition between 1849 and 1870?