America’s History: Printed Page 428

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 392

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 378

1850: Crisis and Compromise

The rapid settlement of California qualified it for admission to the Union. Hoping to avoid an extended debate over slavery, President Taylor advised the settlers to skip the territorial phase and immediately apply for statehood. In November 1849, Californians ratified a state constitution prohibiting slavery, and the president urged Congress to admit California as a free state.

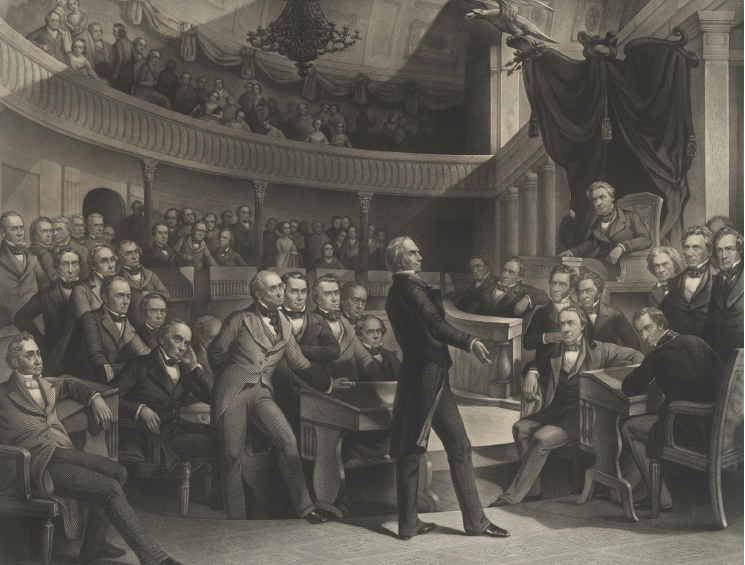

Constitutional Conflict California’s bid for admission produced passionate debates in Congress and four distinct positions regarding the expansion of slavery. First, John C. Calhoun took his usual extreme stance. On the verge of death, Calhoun reiterated his deep resentment of the North’s “long-continued agitation of the slavery question.” To uphold southern honor (and political power), he proposed a constitutional amendment to create a dual presidency, permanently dividing executive power between the North and the South. Calhoun also advanced the radical argument that Congress had no constitutional authority to regulate slavery in the territories. Slaves were property, Calhoun insisted, and the Constitution restricted Congress’s power to abrogate or limit property rights. That argument ran counter to a half century of practice: Congress had prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory in 1787 and had extended that ban to most of the Louisiana Purchase in the Missouri Compromise of 1820. But Calhoun’s assertion that “slavery follows the flag” — that planters could by right take their slave property into new territories — won support in the Deep South.

However, many southerners favored a second, more moderate proposal to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific Ocean. This plan won the backing of Pennsylvanian James Buchanan and other influential northern Democrats. It would guarantee slave owners access to some western territory, including a separate state in southern California.

A third alternative was squatter sovereignty — allowing settlers in a territory to decide the status of slavery. Lewis Cass had advanced this idea in 1848, and Democratic senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois now became its champion. Douglas called his plan “popular sovereignty” to link it to republican ideology, which placed ultimate power in the hands of the people, and it had considerable appeal. Politicians hoped it would remove the explosive issue of slavery from Congress, and settlers welcomed the power it would give them. However, popular sovereignty was a slippery concept. Could residents accept or ban slavery when a territory was first organized? Or must they delay that decision until a territory had enough people to frame a constitution and apply for statehood? No one knew.

For their part, antislavery advocates refused to accept any plan for California or the territories that would allow slavery. Senator Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, elected by a Democratic-Free-Soil coalition, and Senator William H. Seward, a New York Whig, urged a fourth position: that federal legislation restrict slavery within its existing boundaries and eventually extinguish it completely. Condemning slavery as “morally unjust, politically unwise, and socially pernicious” and invoking “a higher law than the Constitution,” Seward demanded bold action to protect freedom, “the common heritage of mankind.”

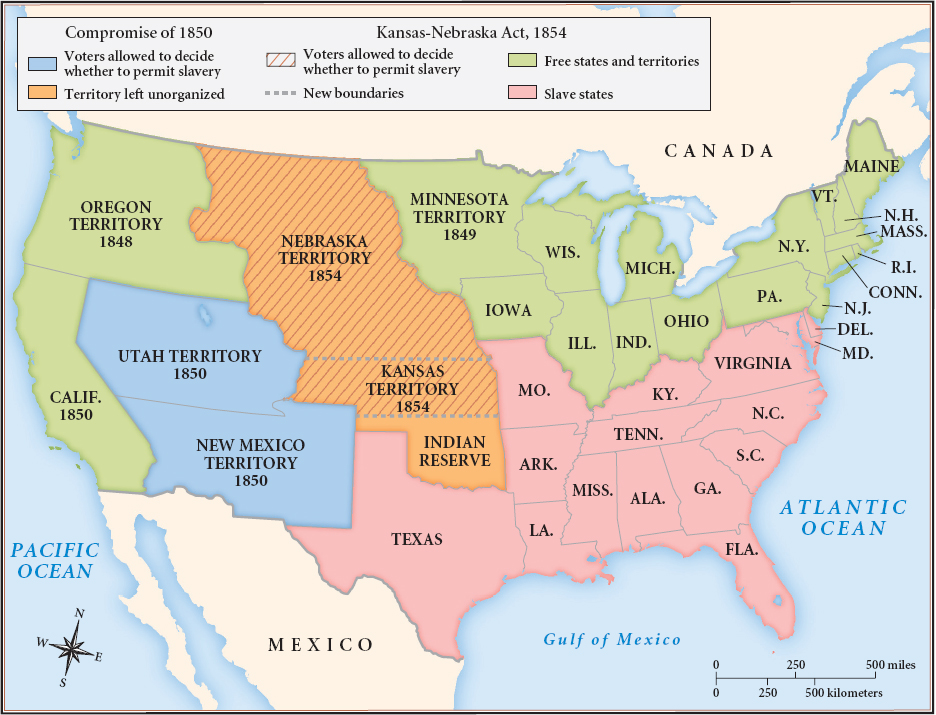

A Complex Compromise Standing on the brink of disaster, senior Whig and Democratic politicians worked desperately to preserve the Union. Aided by Millard Fillmore, who became president in 1850 after Zachary Taylor’s sudden death, Whig leaders Henry Clay and Daniel Webster and Democrat Stephen A. Douglas won the passage of five separate laws known collectively as the Compromise of 1850. To mollify the South, the compromise included a new Fugitive Slave Act giving federal support to slave catchers. To satisfy the North, the legislation admitted California as a free state, resolved a boundary dispute between New Mexico and Texas in favor of New Mexico, and abolished the slave trade (but not slavery) in the District of Columbia. Finally, the compromise organized the rest of the conquered Mexican lands into the territories of New Mexico and Utah and, invoking popular sovereignty, left the issue of slavery in the hands of their residents (Map 13.6).

The Compromise of 1850 preserved national unity by accepting once again the stipulation advanced by the South since 1787: no Union without slavery. Still, southerners feared for the future and threatened secession. Militant activists (or “fire-eaters”) in South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama organized special conventions to safeguard “southern rights.” Georgia congressman Alexander H. Stephens called on convention delegates to prepare “men and money, arms and munitions, etc. to meet the emergency.” A majority of delegates remained committed to the Union, but only on the condition that Congress protect slavery where it existed and grant statehood to any territory that ratified a proslavery constitution. Political wizardry had solved the immediate crisis, but not the underlying issues.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

How did the Compromise of 1850 resolve the various disputes over slavery, and who benefitted more from its terms?