America’s History: Printed Page 433

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 399

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 385

Buchanan’s Failed Presidency

The violence in Kansas dominated the presidential election of 1856. The new Republican Party counted on anger over Bleeding Kansas to boost the party’s fortunes. Its platform denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act and demanded that the federal government prohibit slavery in all the territories. Republicans also called for federal subsidies for transcontinental railroads, reviving a Whig economic proposal popular among midwestern Democrats. For president, the Republicans nominated Colonel John C. Frémont, a free-soiler who had won fame in the conquest of Mexican California.

The Election of 1856 The American Party entered the election with equally high hopes, but like the Whigs and Democrats, it split along sectional lines over slavery. The southern faction of the American Party nominated former Whig president Millard Fillmore, while the northern contingent endorsed Frémont. During the campaign, the Republicans won the votes of many northern Know-Nothings by demanding legislation banning foreign immigrants and imposing high tariffs on foreign manufactures. As a Pennsylvania Republican put it, “Let our motto be, protection to everything American, against everything foreign.” In New York, Republicans campaigned on a reform platform designed to unite “all of the Anti-Slavery, Anti-Popery and Anti-Whiskey” voters.

The Democrats reaffirmed their support for popular sovereignty and the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and they nominated James Buchanan of Pennsylvania. A tall, dignified, and experienced politician, Buchanan was staunchly prosouthern. He won the three-way race with 1.8 million popular votes (45.3 percent) and 174 electoral votes. Frémont polled 1.3 million popular votes (33.2 percent) and 114 electoral votes; Fillmore won 873,000 popular votes (21.5 percent) but captured only 8 electoral votes.

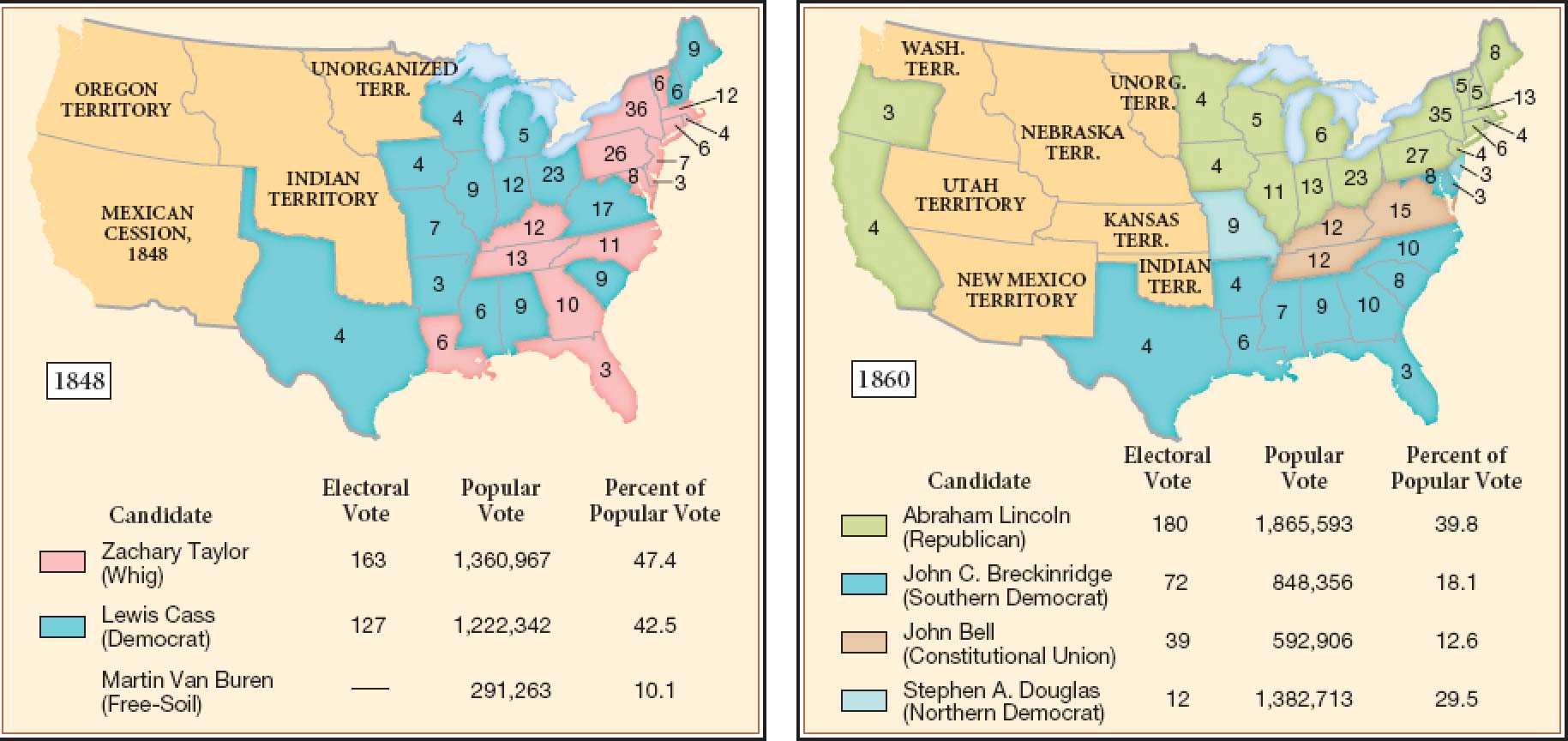

The dramatic restructuring of the political system was now apparent (Map 13.7). With the splintering of the American Party, the Republicans had replaced the Whigs as the second major party. However, Frémont had not won a single vote in the South; had he triumphed, a North Carolina newspaper warned, the result would have been “a separation of the states.” The fate of the republic hinged on President Buchanan’s ability to quiet the passions of the past decade and to hold the Democratic Party — the only national party — together.

Dred Scott: Petitioner for Freedom Events — and his own values and weaknesses — conspired against Buchanan. Early in 1857, the Supreme Court decided the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford, which raised the controversial issue of Congress’s constitutional authority over slavery. Dred Scott was an enslaved African American who had lived for a time with his owner, an army surgeon, in the free state of Illinois and at Fort Snelling in the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase (then part of the Wisconsin Territory), where the Missouri Compromise (1820) prohibited slavery. Scott claimed that residence in a free state and a free territory had made him free. Buchanan opposed Scott’s appeal and pressured the two justices from Pennsylvania to side with their southern colleagues. Seven of the nine justices declared that Scott was still a slave, but they disagreed on the legal rationale (Thinking Like a Historian).

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of Maryland, a slave owner himself, wrote the most influential opinion. He declared that Negroes, whether enslaved or free, could not be citizens of the United States and that Scott therefore had no right to sue in federal court. That argument was controversial, given that free blacks were citizens in many states and therefore had access to the federal courts. Taney then made two even more controversial claims. First, he endorsed John C. Calhoun’s argument that the Fifth Amendment, which prohibited “taking” of property without due process of law, meant that Congress could not prevent southern citizens from moving their slave property into the territories and owning it there. Consequently, the chief justice concluded, the provisions of the Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise that prohibited slavery had never been constitutional. Second, Taney declared that Congress could not give to territorial governments any powers that it did not possess, such as the authority to prohibit slavery. Taney thereby endorsed Calhoun’s interpretation of popular sovereignty: only when settlers wrote a constitution and requested statehood could they prohibit slavery.

In a single stroke, Taney had declared the Republican proposals to restrict the expansion of slavery through legislation to be unconstitutional. The Republicans could never accept the legitimacy of Taney’s constitutional arguments, which indeed had significant flaws. Led by Senator Seward of New York, they accused the chief justice and President Buchanan of participating in the Slave Power conspiracy.

Buchanan then added fuel to the raging constitutional fire. Ignoring reports that antislavery residents held a clear majority in Kansas, he refused to allow a popular vote on the proslavery Lecompton constitution and in 1858 strongly urged Congress to admit Kansas as a slave state. Angered by Buchanan’s machinations, Stephen Douglas, the most influential Democratic senator and architect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, broke with the president and persuaded Congress to deny statehood to Kansas. (Kansas would enter the Union as a free state in 1861.) Still determined to aid the South, Buchanan resumed negotiations to buy Cuba in December 1858. By pursuing a proslavery agenda — first in Dred Scott and then in Kansas and Cuba — Buchanan widened the split in his party and the nation.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

Why did northern Democratic presidents, such as Pierce and Buchanan, adopt prosouthern policies?