America’s History: Printed Page 437

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 402

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 387

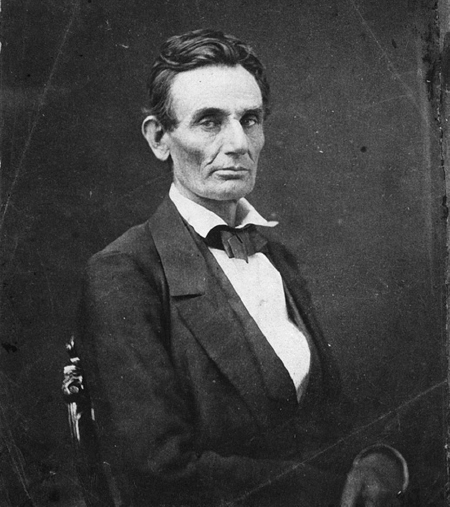

Lincoln’s Political Career

The middle-class world of storekeepers, lawyers, and entrepreneurs in the small towns of the Ohio River Valley shaped Lincoln’s early career. He came from a hardscrabble yeoman farm family that was continually on the move — from Kentucky, where Lincoln was born in 1809, to Indiana, and then to Illinois. In 1831, Lincoln rejected his father’s life as a subsistence farmer and became a store clerk in New Salem, Illinois. Socially ambitious, Lincoln won entry to the middle class by mastering its culture; he joined the New Salem Debating Society, read Shakespeare, and studied law.

Admitted to the bar in 1837, Lincoln moved to Springfield, the new state capital. There, he met Mary Todd, the cultured daughter of a Kentucky banker; they married in 1842. Her tastes were aristocratic; his were humble. She was volatile; he was easygoing but suffered bouts of depression that tried her patience and tested his character.

An Ambitious Politician Lincoln’s ambition was “a little engine that knew no rest,” a close associate remarked, and it propelled him into politics. An admirer of Henry Clay, Lincoln joined the Whig Party and won election to four terms in the Illinois legislature, where he promoted education, banks, canals, and railroads. He became a dexterous party politician, adept in the use of patronage and the passage of legislation.

In 1846, the rising lawyer-politician won election to a Congress that was bitterly divided over the Wilmot Proviso. Lincoln believed that human bondage was unjust but doubted that the federal government had the constitutional authority to tamper with slavery. With respect to the Mexican War, he took a middle ground by voting for military appropriations but also for the Wilmot Proviso’s ban on slavery in any acquired territories. Lincoln also introduced legislation that would require the gradual (and thus compensated) emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia. To avoid future racial strife, he favored the colonization of freed blacks in Africa or South America. Both abolitionists and proslavery activists heaped scorn on Lincoln’s middle-of-the-road policies, and he lost his bid for reelection. Dismayed by the rancor of ideological debate, he withdrew from politics and prospered as a lawyer by representing railroads and manufacturers.

Lincoln returned to the political fray because of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Shocked by the act’s repeal of the Missouri Compromise and Senator Douglas’s advocacy of popular sovereignty, Lincoln reaffirmed his opposition to slavery in the territories. He now likened slavery to a cancer that had to be cut out if the nation’s republican ideals and moral principles were to endure.

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates Abandoning the Whigs, Lincoln quickly emerged as the leading Republican in Illinois, and in 1858 he ran for the U.S. Senate seat held by Douglas. Lincoln pointed out that the proslavery Supreme Court might soon declare that the Constitution “does not permit a state to exclude slavery,” just as it had decided in Dred Scott that “neither Congress nor the territorial legislature” could ban slavery in a territory. In that event, he warned, “we shall awake to the reality … that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave state.” This prospect informed Lincoln’s famous “House Divided” speech. Quoting the biblical adage “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” he predicted that American society “cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. … It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

The Senate race in Illinois attracted national interest because of Douglas’s prominence and Lincoln’s reputation as a formidable speaker. During a series of seven debates, Douglas declared his support for white supremacy: “This government was made by our fathers, by white men for the benefit of white men,” he said, attacking Lincoln for supporting “negro equality.” Lincoln parried Douglas’s racist attacks by arguing that free blacks should have equal economic opportunities but not equal political rights. Taking the offensive, he asked how Douglas could accept the Dred Scott decision (which protected slave property in the territories) yet advocate popular sovereignty (which allowed settlers to exclude slavery). Douglas responded with the so-called Freeport Doctrine: that a territory’s residents could exclude slavery by not adopting laws to protect it. That position pleased neither proslavery nor antislavery advocates. Nonetheless, when Democrats won a narrow majority in the state legislature, they reelected Douglas to the U.S. Senate.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

What was Lincoln’s position on slavery and people of African descent during the 1840s and 1850s?