America’s History: Printed Page 438

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 404

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 389

The Union Under Siege

The debates with Douglas gave Lincoln a national reputation, and in the election of 1858 the Republican Party won control of the U.S. House of Representatives.

The Rise of Radicalism Shaken by the Republicans’ advance, southern Democrats divided again into moderates and fire-eaters. The moderates, who included Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, strongly defended “southern rights” and demanded ironclad political or constitutional protections for slavery. The fire-eaters — men such as Robert Barnwell Rhett of South Carolina and William Lowndes Yancey of Alabama — repudiated the Union and actively promoted secession. Radical antislavery northerners likewise took a strong stance. Senator Seward of New York declared that freedom and slavery were locked in “an irrepressible conflict,” and ruthless abolitionist John Brown, who had perpetrated the Pottawatomie massacre, showed what that might mean. In October 1859, Brown led eighteen heavily armed black and white men in a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown hoped to arm slaves with the arsenal’s weapons and mount a major rebellion to end slavery.

Republican leaders condemned Brown’s unsuccessful raid, but Democrats called his plot “a natural, logical, inevitable result of the doctrines and teachings of the Republican party.” When the state of Virginia sentenced Brown to be hanged, transcendentalist reformers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed him a “saint awaiting his martyrdom.” The slaveholding states looked to the future with terror. “The aim of the present black republican organization is the destruction of the social system of the Southern States,” warned one newspaper. Once Republicans came to power, another cautioned, they “would create insurrection and servile war in the South — they would put the torch to our dwellings and the knife to our throats.”

Nor could the South count any longer on the Democratic Party to protect its interests. At the party’s convention in April 1860, northern Democrats rejected Jefferson Davis’s proposal to protect slavery in the territories, and delegates from eight southern states quit the meeting. At a second Democratic convention, northern and midwestern delegates nominated Stephen Douglas for president; meeting separately, southern Democrats nominated the sitting vice president, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.

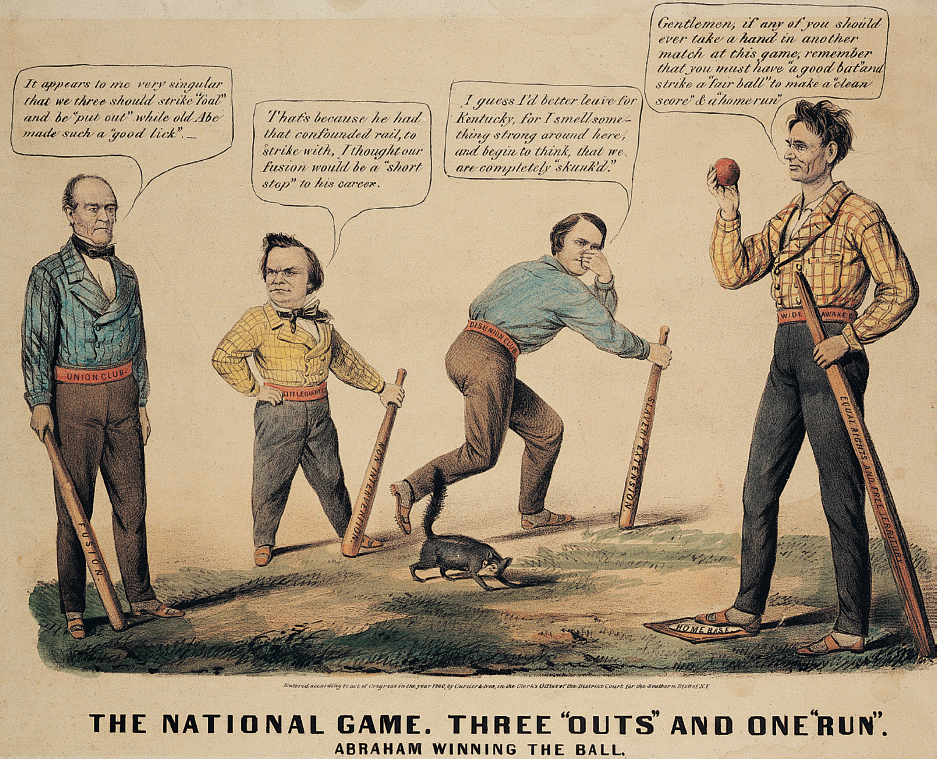

The Election of 1860 With the Democrats divided, the Republicans sensed victory. They courted white voters with a free-soil platform that opposed both slavery and racial equality: “Missouri for white men and white men for Missouri,” declared that state’s Republican platform. The national Republican convention chose Lincoln as its presidential candidate because he was more moderate on slavery than the best-known Republicans, Senators William Seward of New York and Salmon Chase of Ohio. Lincoln also conveyed a compelling egalitarian image that appealed to smallholding farmers, wage earners, and midwestern voters.

The Republican strategy worked. Although Lincoln received less than 1 percent of the popular vote in the South and only 40 percent of the national poll, he won every northern and western state except New Jersey, giving him 180 (of 303) electoral votes and an absolute majority in the electoral college. Breckinridge took 72 electoral votes by sweeping the Deep South and picking up Delaware, Maryland, and North Carolina. Douglas won 30 percent of the popular ballot but secured only 51 electoral votes in Missouri and New Jersey. The Republicans had united voters in the Northeast, Midwest, and Pacific coast behind free soil.

A revolution was in the making. “Oh My God!!! This morning heard that Lincoln was elected,” Keziah Brevard, a widowed South Carolina plantation mistress and owner of two hundred slaves, scribbled in her diary. “Lord save us.” Slavery had permeated the American federal republic so thoroughly that southerners saw it as a natural part of the constitutional order — an order that was now under siege. Fearful of a massive black uprising, Chief Justice Taney recalled “the horrors of St. Domingo [Haiti].” At the very least, warned John Townsend of South Carolina, a Republican administration in Washington would suppress “the inter-State slave trade” and thereby “cripple this vital Southern institution of slavery.” To many southerners, it seemed time to think carefully about Lincoln’s 1858 statement that the Union must “become all one thing, or all the other.”

|

To see a longer excerpt of Keziah Brevard’s diary, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What was the relationship between the collapse of the Second Party System and the Republican victory in the election of 1860?