America’s History: Printed Page 412

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 377

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 365

The Push to the Pacific

As expansionists developed continental ambitions, the term Manifest Destiny captured those dreams. John L. O’Sullivan, editor of the Democratic Review, coined the phrase in 1845: “Our manifest destiny is to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” Underlying the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny was a sense of Anglo-American cultural and racial superiority: the “inferior” peoples who lived in the Far West — Native Americans and Mexicans — would be subjected to American dominion, taught republicanism, and converted to Protestantism.

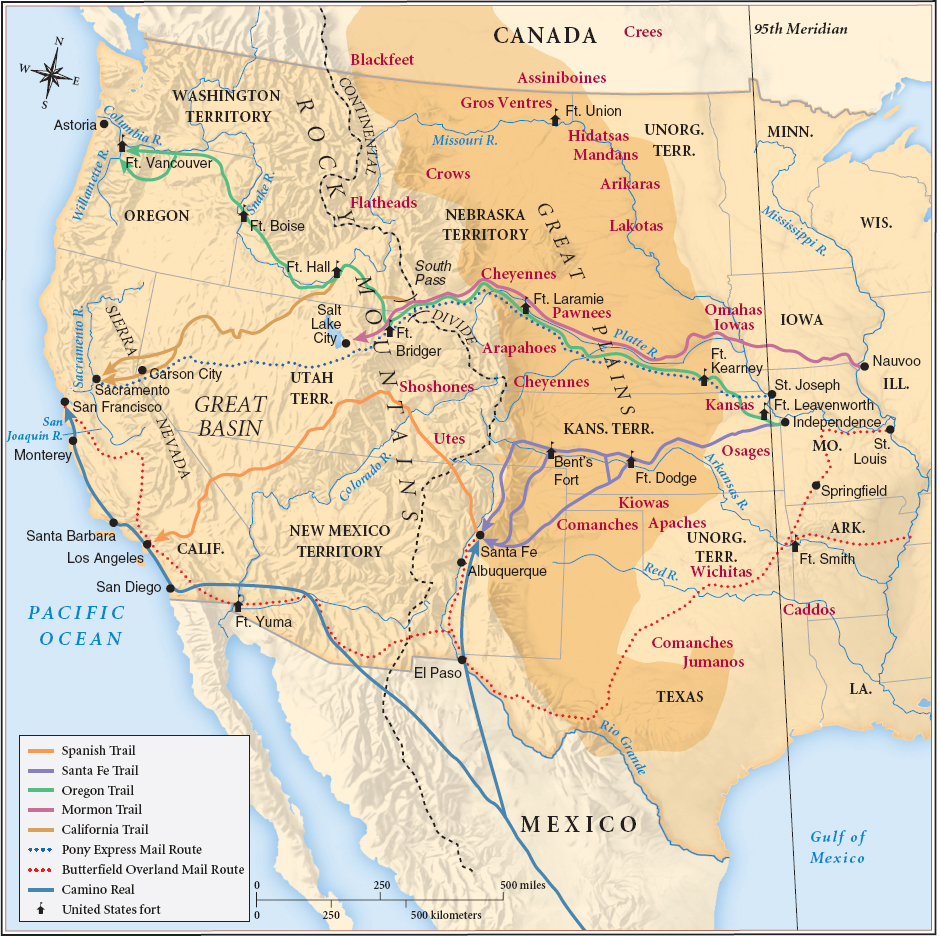

Oregon Land-hungry farmers of the Ohio River Valley had already cast their eyes toward the fertile lands of the Oregon Country, a region that stretched along the Pacific coast between the Mexican province of California and Russian settlements in Alaska. Since 1818, a British-American agreement had allowed settlement by people from both nations. The British-run Hudson’s Bay Company developed a lucrative fur business north of the Columbia River, while Methodist missionaries and a few hundred American farmers settled to the south, in the Willamette Valley (Map 13.1).

In 1842, American interest in Oregon increased dramatically. The U.S. Navy published a glowing report of fine harbors in the Puget Sound, which New England merchants trading with China were already using. Simultaneously, a party of one hundred farmers journeyed along the Oregon Trail, which fur traders and explorers had blazed from Independence, Missouri, across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains (Map 13.2). Their letters from Oregon told of a mild climate and rich soil.

“Oregon fever” suddenly raged. A thousand men, women, and children — with a hundred wagons and five thousand oxen and cattle — gathered in Independence in April 1843. As the spring mud dried, they began their six-month trek, hoping to miss the winter snows. Another 5,000 settlers, mostly yeomen farm families from the southern border states (Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee), set out over the next two years. These pioneers overcame floods, dust storms, livestock deaths, and a few armed encounters with native peoples before reaching Oregon, a journey of 2,000 miles.

By 1860, about 250,000 Americans had braved the Oregon Trail, with 65,000 heading for Oregon, 185,000 to California, and others staying in Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana. More than 34,000 migrants died, mostly from disease and exposure; fewer than 500 deaths resulted from Indian attacks. The walking migrants wore paths 3 feet deep, and their wagons carved 5-foot ruts across sandstone formations in southern Wyoming — tracks that are visible today. Women found the trail especially difficult; in addition to their usual chores and the new work of driving wagons and animals, they lacked the support of female kin and the security of their domestic space. About 2,500 women endured pregnancy or gave birth during the long journey, and some did not survive. “There was a woman died in this train yesterday,” Jane Gould Tortillott noted in her diary. “She left six children, one of them only two days old.”

The 10,000 migrants who made it to Oregon in the 1840s mostly settled in the Willamette Valley. Many families squatted on 640 acres and hoped Congress would legalize their claims so that they could sell surplus acreage to new migrants. The settlers quickly created a race- and gender-defined polity by restricting voting to a “free male descendant of a white man.”

California About 3,000 other early pioneers ended up in the Mexican province of California. They left the Oregon Trail along the Snake River, trudged down the California Trail, and mostly settled in the interior along the Sacramento River, where there were few Mexicans. A remote outpost of Spain’s American empire, California had few nonnative residents until the 1770s, when Spanish authorities built a chain of forts and religious missions along the Pacific coast. When Mexico achieved independence in 1821, its government took over the Franciscan-run missions and freed the 20,000 Indians whom the monks had persuaded or coerced into working on them. Some mission Indians rejoined their tribes, but many intermarried with mestizos (Mexicans of mixed Spanish and Indian ancestry). They worked on huge ranches — the 450 estates created by Mexican officials and bestowed primarily on their families and political allies. The owners of these vast properties (averaging 19,000 acres) mostly raised Spanish cattle, prized for their hides and tallow.

The ranches soon linked California to the American economy. New England merchants dispatched dozens of agents to buy leather for the booming Massachusetts boot and shoe industry and tallow to make soap and candles. Many agents married the daughters of the elite Mexican ranchers — the Californios — and adopted their manners, attitudes, and Catholic religion. A crucial exception was Thomas Oliver Larkin, a successful merchant in the coastal town of Monterey. Although Larkin worked closely with Mexican politicians and landowners, he remained strongly American in outlook.

Like Larkin, the American migrants in the Sacramento River Valley did not assimilate into Mexican society. Some hoped to emulate the Americans in Texas by colonizing the country and then seeking annexation. However, in the early 1840s, these settlers numbered only about 1,000, far outnumbered by the 7,000 Mexicans who lived along the coast.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

Did the idea of Manifest Destiny actually cause events, such as the political support for territorial expansion, or simply justify actions taken for other reasons?