America’s History: Printed Page 418

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 384

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 371

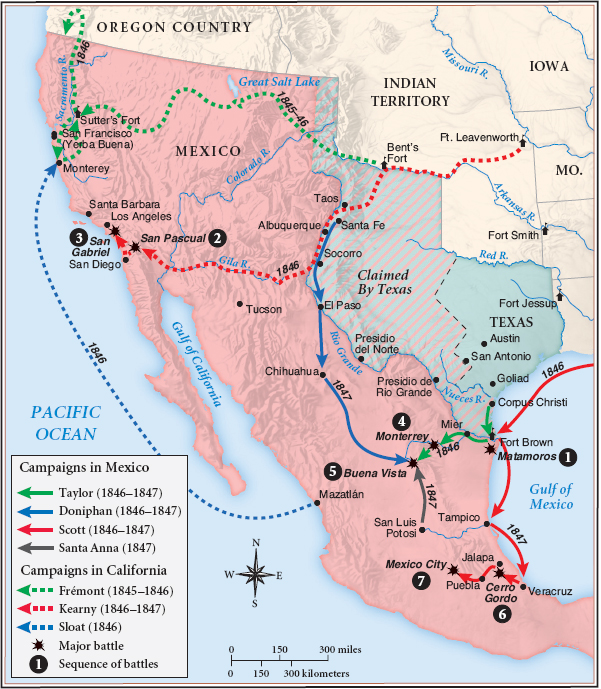

The War with Mexico, 1846–1848

Since gaining independence in 1821, Mexico had not prospered. Its civil wars and political instability produced a stagnant economy, a weak government, and modest tax revenues, which a bloated bureaucracy and debt payments to European bankers quickly devoured. Although the distant northern provinces of California and New Mexico remained undeveloped and sparsely settled, with a Spanish-speaking population of only 75,000 in 1840, Mexican officials vowed to preserve their nation’s historic boundaries. When its breakaway province of Texas prepared to join the American Union, Mexico suspended diplomatic relations with the United States.

Polk’s Expansionist Program President Polk now moved quickly to acquire Mexico’s other northern provinces. He hoped to foment a revolution in California that, like the 1836 rebellion in Texas, would lead to annexation. In October 1845, Secretary of State James Buchanan told merchant Thomas Oliver Larkin, now the U.S. consul for the Mexican province, to encourage influential Californios to seek independence and union with the United States. To add military muscle to this scheme, Polk ordered American naval commanders to seize San Francisco Bay and California’s coastal towns in case of war with Mexico. The president also instructed the War Department to dispatch Captain John C. Frémont and an “exploring” party of soldiers into Mexican territory. By December 1845, Frémont’s force had reached California’s Sacramento River Valley.

With these preparations in place, Polk launched a secret diplomatic initiative: he sent Louisiana congressman John Slidell to Mexico, telling him to secure the Rio Grande boundary for Texas and to buy the provinces of California and New Mexico for $30 million. However, Mexican officials refused to meet with Slidell.

Events now moved quickly toward war. Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor and an American army of 2,000 soldiers to occupy disputed lands between the Nueces River (the historic southern boundary of Spanish Texas) and the Rio Grande, which the Republic of Texas had claimed as its border with Mexico. “We were sent to provoke a fight,” recalled Ulysses S. Grant, then a young officer serving with Taylor, “but it was essential that Mexico should commence it.” When the armies clashed near the Rio Grande in May 1846, Polk delivered the war message he had drafted long before. Taking liberties with the truth, the president declared that Mexico “has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon the American soil.” Ignoring pleas by some Whigs for a negotiated settlement, an overwhelming majority in Congress voted for war — a decision greeted with great popular acclaim. To avoid a simultaneous war with Britain, Polk retreated from his demand for “fifty-four forty or fight” and in June 1846 accepted British terms that divided the Oregon Country at the forty-ninth parallel.

American Military Successes American forces in Texas quickly established their military superiority. Zachary Taylor’s army crossed the Rio Grande; occupied the Mexican city of Matamoros; and, after a fierce six-day battle in September 1846, took the interior Mexican town of Monterrey. Two months later, a U.S. naval squadron in the Gulf of Mexico seized Tampico, Mexico’s second most important port. By the end of 1846, the United States controlled much of northeastern Mexico (Map 13.3).

Fighting also broke out in California. In June 1846, naval commander John Sloat landed 250 marines in Monterey and declared that California “henceforward will be a portion of the United States.” Simultaneously, American settlers in the Sacramento River Valley staged a revolt and, supported by Frémont’s force, captured the town of Sonoma, where they proclaimed the independence of the “Bear Flag Republic.” To cement these victories, Polk ordered army units to capture Santa Fe in New Mexico and then march to southern California. Despite stiff Mexican resistance, American forces secured control of California early in 1847.

Polk expected these victories to end the war, but he underestimated the Mexicans’ national pride and the determination of President Santa Anna. In February 1847 in the Battle of Buena Vista, Santa Anna nearly defeated Taylor’s army in northeastern Mexico. With most Mexican troops deployed in the north, Polk approved General Winfield Scott’s plan to capture the port of Veracruz and march 260 miles to Mexico City. An American army of 14,000 seized the Mexican capital in September 1847. That American victory cost Santa Anna his presidency, and a new Mexican government made a forced peace with the United States.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How was the American acquisition of California similar to, and different from, the American-led creation of the Texas Republic?