America’s History: Printed Page 458

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

Military Deaths — and Lives Saved — During the Civil War

The Civil War, like all wars before and since, encouraged innovation in both the destruction and the saving of human life. More than 620,000 soldiers — 360,000 on the Union side and 260,000 Confederates — died during the war, about 20 percent of those who served. However, thanks to advances in camp hygiene and battlefield treatment, the Union death rate was about 54–58 per 1,000 soldiers per year, less than half the level for British and French troops during the Crimean War of 1854–1855.

Report by surgeon Charles S. Tipler, medical director of the Army of the Potomac, January 4, 1862. Most Civil War deaths came from disease. The major killers were bacterial intestinal diseases — typhoid fever, diarrhea, and dysentery — which spread because of unsanitary conditions in the camps.

The aggregate strength of the forces from which I have received reports is 142,577. Of these, 47,836 have been under treatment in the field and general hospitals, 35,915 of whom have been returned to duty, and 281 have died; 9,281 remained under treatment at the end of the month; …

The diseases from which our men have suffered most have been continued remittent and typhoid fevers, measles, diarrhea, dysentery, and the various forms of catarrh [heavy discharge of mucus from the nose]. Of all the scourges incident to armies in the field I suppose that chronic diarrheas and dysenteries have always been the most prevalent and the most fatal. I am happy to say that in this army they are almost unknown. We have but 280 cases of chronic diarrhea and 69 of chronic dysentery reported in the month of November.

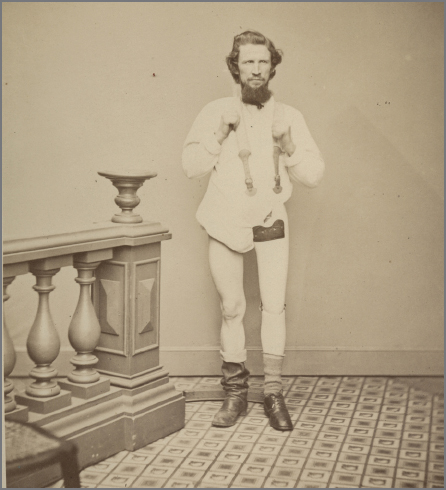

Minie ball wounds: femur shot by Springfield 1862 rifle and Private George W. Lemon, 1867.

Ninety percent of battle casualties were the victims of a new technology: musket-rifles that fired lethal soft-lead bullets called minie balls (after their inventor, Claude-Étienne Minié). The rifle-musket revolutionized military strategy by enormously strengthening defensive forces. Infantrymen could now kill reliably at 300 yards — triple the previous range of muskets. Initially, the new technology baffled commanders, who continued to use the tactics perfected during the heyday of the musket and bayonet charge, sending waves of infantrymen against enemy positions.

A minie ball strike to the abdomen, chest, or head was usually fatal, but injuries to the limbs gave some hope of survival, given advances in battlefield surgery. When Private George W. Lemon suffered a minie ball wound to his femur similar to the one shown here (below), surgeons amputated his leg below the hip and, after the war, fitted him with a prosthetic leg.

Source: National Museum of Health & Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

Source: National Museum of Health & Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Source: Courtesy National Library of Medicine.

Source: Courtesy National Library of Medicine.Kate Cumming, April 23, 1862, journal entry on treating a Confederate victim after the Battle of Shiloh. Union surgeons performed 29,980 battlefield amputations during the Civil War. Confederate records are less complete, but surgeons apparently undertook about 28,000 amputations. They quickly removed limbs too shattered to mend, which increased the chances of survival. According to one witness, “surgeons and their assistants, stripped to the waist and bespattered with blood, stood around, some holding the poor fellows while others, armed with long, bloody knives and saws, cut and sawed away with frightful rapidity, throwing the mangled limbs on a pile nearby as soon as removed.” This journal entry from a young Confederate nurse in Corinth, Mississippi, describes the plight of one such victim after the Battle of Shiloh.

A young man whom I have been attending is going to have his arm cut off. Poor fellow! I am doing all I can to cheer him. He says that he knows that he will die, as all who have had limbs amputated in this hospital have died. … He lived only a few hours after his amputation.

William Williams Keen, MD, “Surgical Reminiscences of the Civil War,” 1905. Although 73 percent of the Union amputees survived the war, infected wounds — deadly gangrene — took the lives of most soldiers who suffered certain gunshot injuries in this pre-antibiotic, pre-antiseptic era. Keen, who later became the first brain surgeon in the United States, served as a surgeon in the Union army.

Not more than one incontestable example of recovery from a gunshot wound of the stomach and not a single incontestable case of wound of the small intestines are recorded during the entire war among the almost 250,000 wounded. …

Of 852 amputations of the shoulder-joint, 236 died, a mortality of 28.5 per cent. Of 66 cases of amputation of the hip-joint, 55, or 83.3 per cent died. Of 155 cases of trephining [cutting a hole in the skull to relieve pressure], 60 recovered and 95 died, a mortality of over 61 per cent. Of 374 ligations of the femoral artery, 93 recovered and 281 died, a mortality of over 75 per cent.

These figures afford a striking evidence of the dreadful mortality of military surgery in the days before antisepsis and first-aid packages. Happily such death-rates can never again be seen, at least in civilized warfare.

John Tooker, MD, “Aspects of Medicine, Nursing, and the Civil War,” 2007. The Union doctor Jonathan Letterman pioneered a new method of battlefield triage that was adopted by the entire army in 1864.

Letterman had devised an efficient and, for the times, modern system of mass casualty management, beginning with first aid adjacent to the battlefield, removal of the wounded by an organized ambulance system to field hospitals for urgent and stabilizing treatment, such as wound closure and amputation, and then referral to general hospitals for longer term definitive management. This three-stage approach to casualty management, strengthened by effective and efficient transport, earned Letterman the title of “The Father of Battlefield Medicine.”

Sources: (1) The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1889), Series 1, Vol. 5 (Part V), 111–112; (3) Kate Cumming, A Journal of Hospital Life in the Confederate Army of Tennessee (Louisville, KY: John P. Morton & Company, 1866), 19; (4) William Williams Keen, “Surgical Reminiscences of the Civil War,” in Addresses and Other Papers (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1905), 433–434; (5) John Tooker, “Antietam: Aspects of Medicine, Nursing, and the Civil War,” National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

Based on Tipler’s report (source 1), would you say the Union army was healthy or unhealthy? Ready for battle or not?

Question

Consider sources 2–4. How do you think the reentry of tens of thousands of maimed veterans into civil society affected American culture?

Question

What do sources 3–5 suggest about the successes and limitations of battlefield medicine during the Civil War?

Question

Consider the Civil War in the context of the Industrial Revolution. What was the impact of factory production and technological advances on the number of weapons and their killing power? And how might the organizational innovations of the Industrial Revolution pertain to the conflict? In this regard, what do you make of the new method of battlefield triage pioneered by Union doctor Jonathan Letterman (source 5)?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

As a “total war” the Civil War involved the citizenry as well as the military, marshaling all of the two societies’ resources and ingenuity. Using your understanding of these documents and the textbook, write an essay that discusses the relation of the war to technology, medicine, public finance, and the lives of women on the battle lines and the home front.