America’s History: Printed Page 456

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 421

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 406

Mobilizing Resources

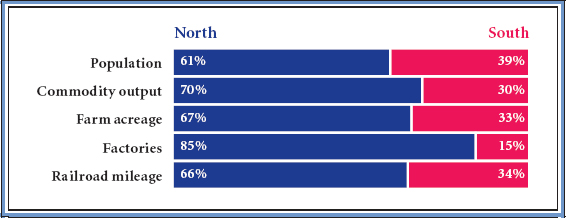

Wars are usually won by the side that possesses greater resources. In that regard, the Union had a distinct advantage. With nearly two-thirds of the nation’s population, two-thirds of the railroad mileage, and almost 90 percent of the industrial output, the North’s economy was far superior to that of the South (Figure 14.2). Furthermore, many of its arms factories were equipped for mass production.

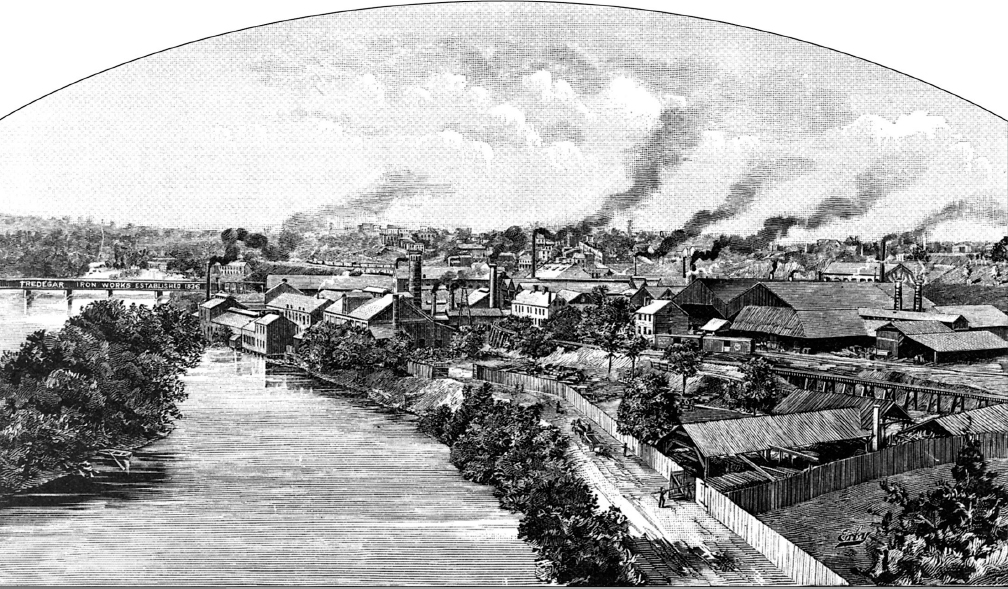

Still, the Confederate position was far from weak. Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee had substantial industrial capacity. Richmond, with its Tredegar Iron Works, was an important manufacturing center, and in 1861 it acquired the gun-making machinery from the U.S. armory at Harpers Ferry. The production at the Richmond armory, the purchase of Enfield rifles from Britain, and the capture of 100,000 Union guns enabled the Confederacy to provide every infantryman with a modern rifle-musket by 1863.

Moreover, with 9 million people, the Confederacy could mobilize enormous armies. Enslaved blacks, one-third of the population, became part of the war effort by producing food for the army and raw cotton for export. Confederate leaders counted on King Cotton — the leading American export and a crucial staple of the nineteenth-century economy — to purchase clothes, boots, blankets, and weapons from abroad. Leaders also saw cotton as a diplomatic weapon that would persuade Britain and France, which had large textile industries, to assist the Confederacy. However, British manufacturers had stockpiled cotton and developed new sources in Egypt and India. Still, the South received some foreign support. Although Britain never recognized the Confederacy as an independent nation, it treated the rebel government as a belligerent power — with the right under international law to borrow money and purchase weapons. The odds, then, did not necessarily favor the Union, despite its superior resources.

Republican Economic and Fiscal Policies To mobilize northern resources, the Republican-dominated Congress enacted a neomercantilist program of government-assisted economic development that far surpassed Henry Clay’s American System. The Republicans imposed high tariffs (averaging nearly 40 percent) on various foreign goods, thereby encouraging domestic industries. To boost agricultural output, they offered “free land” to farmers. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave settlers the title to 160 acres of public land after five years of residence. To create an integrated national banking system (far more powerful than the First and Second Banks of the United States), Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase forced thousands of local banks to accept federal charters and regulations.

Finally, the Republican Congress implemented Clay’s program for a nationally financed transportation system. Expansion to the Pacific, the California gold rush, and subsequent discoveries of gold, silver, copper, and other metals in Nevada, Montana, and other western lands had revived demands for such a network. Therefore, in 1862, Congress chartered the Union Pacific and Central Pacific companies to build a transcontinental railroad line and granted them lavish subsidies. This economic program won the allegiance of farmers, workers, and entrepreneurs and bolstered the Union’s ability to fight a long war.

New industries sprang up to provide the Union army — and its 1.5 million men — with guns, clothes, and food. Over the course of the war, soldiers consumed more than half a billion pounds of pork and other packed meats. To meet this demand, Chicago railroads built new lines to carry thousands of hogs and cattle to the city’s stockyards and slaughterhouses. By 1862, Chicago had passed Cincinnati as the meatpacking capital of the nation, bringing prosperity to thousands of midwestern farmers and great wealth to Philip D. Armour and other meatpacking entrepreneurs.

Bankers and financiers likewise found themselves pulled into the war effort. The annual spending of the Union government shot up from $63 million in 1860 to more than $865 million in 1864. To raise that enormous sum, the Republicans created a modern system of public finance that secured funds in three ways. First, the government increased tariffs; placed high duties on alcohol and tobacco; and imposed direct taxes on business corporations, large inheritances, and the incomes of wealthy citizens. These levies paid about 20 percent of the cost. Second, interest-paying bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury financed another 65 percent. The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 forced most banks to buy those bonds; and Philadelphia banker and Treasury Department agent Jay Cooke used newspaper ads and 2,500 subagents to persuade a million northern families to buy them.

The Union paid the remaining 15 percent by printing paper money. The Legal Tender Act of 1862 authorized $150 million in paper currency — soon known as greenbacks — and required the public to accept them as legal tender. Like the Continental currency of the Revolutionary era, greenbacks could not be exchanged for specie; however, the Treasury issued a limited amount of paper money, so it lost only a small part of its face value.

If a modern fiscal system was one result of the war, immense concentrations of capital in many industries — meatpacking, steel, coal, railroads, textiles, shoes — was another. The task of supplying the huge war machine, an observer noted, gave a few men “the command of millions of money.” Such massed financial power threatened not only the prewar society of small producers but also the future of democratic self-government (America Compared). Americans “are never again to see the republic in which we were born,” lamented abolitionist and social reformer Wendell Phillips.

The South Resorts to Coercion and Inflation The economic demands on the South were equally great, but, true to its states’ rights philosophy, the Confederacy initially left most matters to the state governments. However, as the realities of total war became clear, Jefferson Davis’s administration took extraordinary measures. It built and operated shipyards, armories, foundries, and textile mills; commandeered food and scarce raw materials such as coal, iron, copper, and lead; requisitioned slaves to work on fortifications; and directly controlled foreign trade.

The Confederate Congress and ordinary southern citizens opposed many of Davis’s initiatives, particularly those involving taxes. The Congress refused to tax cotton exports and slaves, the most valuable property held by wealthy planters, and the urban middle classes and yeomen farm families refused to pay more than their fair share. Consequently, the Confederacy covered less than 10 percent of its expenditures through taxation. The government paid another 30 percent by borrowing, but wealthy planters and foreign bankers grew increasingly fearful that the South would never redeem its bonds.

Consequently, the Confederacy paid 60 percent of its war costs by printing paper money. The flood of currency created a spectacular inflation: by 1865, prices had risen to ninety-two times their 1861 level. As food prices soared, riots erupted in more than a dozen southern cities and towns. In Richmond, several hundred women broke into bakeries, crying, “Our children are starving while the rich roll in wealth.” In Randolph County, Alabama, women confiscated grain from a government warehouse “to prevent starvation of themselves and their families.” As inflation spiraled upward, southerners refused to accept paper money, whatever the consequences. When South Carolina storekeeper Jim Harris refused the depreciated currency presented by Confederate soldiers, they raided his storehouse and, he claimed, “robbed it of about five thousand dollars worth of goods.” Army supply officers likewise seized goods from merchants and offered payment in worthless IOUs. Facing a public that feared strong government and high taxation, the Confederacy could sustain the war effort only by seizing its citizens’ property — and by championing white supremacy: President Davis warned that a Union victory would destroy slavery “and reduce the whites to the degraded position of the African race.”

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did the economic policies of the Republican-controlled Congress redefine the character of the federal government?