America’s History: Printed Page 466

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 429

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 413

Soldiers and Strategy

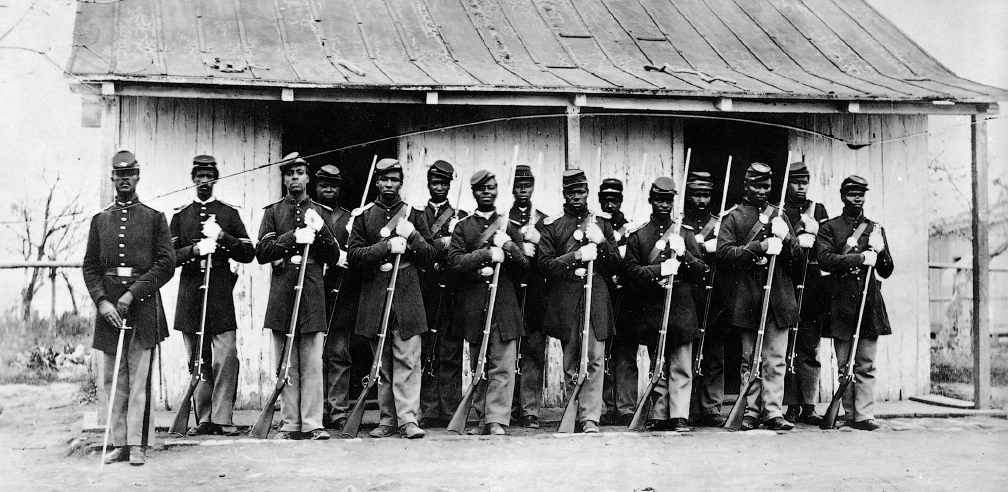

The promotion of aggressive generals and the enlistment of African American soldiers allowed the Union to prosecute the war vigorously. As early as 1861, free African Americans and fugitive slaves had volunteered, both to end slavery and, as Frederick Douglass put it, to win “the right to citizenship.” Yet many northern whites refused to serve with blacks. “I am as much opposed to slavery as any of them,” a New York soldier told his local newspaper, “but I am not willing to be put on a level with the negro and fight with them.” Union generals also opposed the enlistment of African Americans, doubting they would make good soldiers. Nonetheless, free and contraband blacks formed volunteer regiments in New England, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Kansas.

The Impact of Black Troops The Emancipation Proclamation changed military policy and popular sentiment. The proclamation invited former slaves to serve in the Union army, and northern whites, having suffered thousands of casualties, now accepted that blacks should share in the fighting and dying. A heroic and costly attack by the 54th Massachusetts Infantry on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, in 1863 convinced Union officers of the value of black soldiers. By the spring of 1865, the Lincoln administration had recruited and armed nearly 200,000 African Americans. Without black soldiers, said Lincoln, “we would be compelled to abandon the war in three weeks.”

Military service did not end racial discrimination. Black soldiers initially earned less than white soldiers ($10 a month versus $13) and died, mostly from disease, at higher rates than white soldiers. Nonetheless, African Americans continued to volunteer, seeking freedom and a new social order. “Hello, Massa,” said one black soldier to his former master, who had been taken prisoner. “Bottom rail on top dis time.” The worst fears of the secessionists had come true: through the disciplined agency of the Union army, African Americans had risen in a successful rebellion against slavery, just as six decades earlier enslaved Haitians had won emancipation in the army of Toussaint L’Ouverture.

Capable Generals Take Command As African Americans bolstered the army’s ranks, Lincoln finally found a ruthless commanding general. In March 1864, Lincoln placed General Ulysses S. Grant in charge of all Union armies; from then on, the president determined overall strategy and Grant implemented it. Lincoln favored a simultaneous advance against the major Confederate armies, a strategy Grant had long favored, in order to achieve a decisive victory before the election of 1864.

Grant knew how to fight a war that relied on industrial technology and targeted an entire society. At Vicksburg in July 1863, he had besieged the whole city and forced its surrender. Then, in November, he had used railroads to rescue an endangered Union army near Chattanooga, Tennessee. Grant believed that the cautious tactics of previous Union commanders had prolonged the war. He was willing to accept heavy casualties, a stance that earned him a reputation as a butcher of enemy armies and his own men.

In May 1864, Grant ordered two major offensives. Personally taking charge of the 115,000-man Army of the Potomac, he set out to destroy Lee’s force of 75,000 troops in Virginia. Grant instructed General William Tecumseh Sherman, who shared his harsh outlook, to invade Georgia and take Atlanta. “All that has gone before is mere skirmish,” Sherman wrote as he prepared for battle. “The war now begins.”

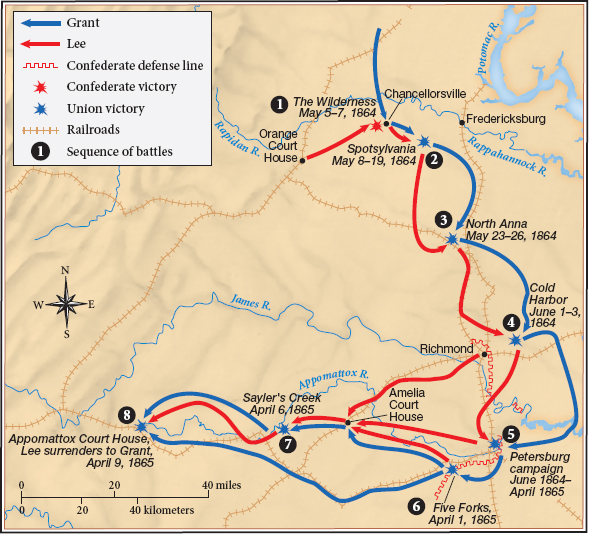

Grant advanced toward Richmond, hoping to force Lee to fight in open fields, where the Union’s superior manpower and artillery would prevail. Remembering his tactical errors at Gettysburg, Lee remained in strong defensive positions and attacked only when he held an advantage. The Confederate general seized that opportunity twice in May 1864, winning costly victories at the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. At Spotsylvania, the troops fought at point-blank range; an Iowa recruit recalled “lines of blue and grey [soldiers firing] into each other’s faces; for an hour and a half.” Despite heavy losses in these battles and then at Cold Harbor, Grant drove on (Map 14.5). His attacks severely eroded Lee’s forces, which suffered 31,000 casualties, but Union losses were even higher: 55,000 killed or wounded.

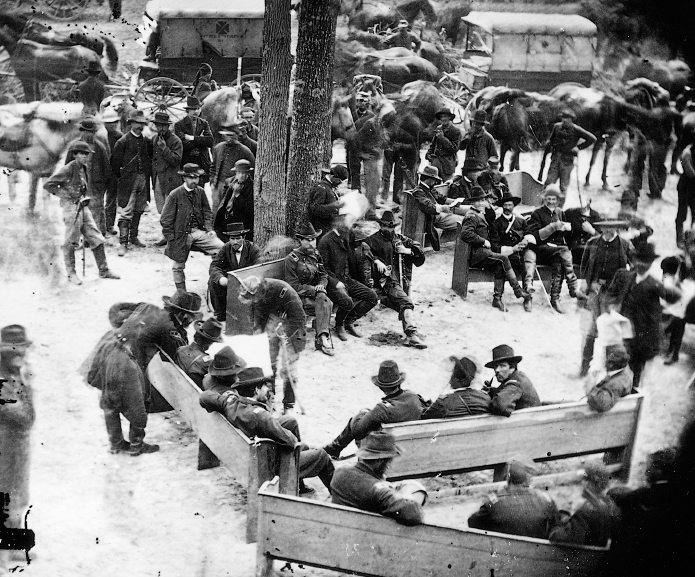

Stalemate The fighting took a heavy psychological toll. “Many a man has gone crazy since this campaign began from the terrible pressure on mind and body,” observed a Union captain. As morale declined, soldiers deserted. In June 1864, Grant laid siege to Petersburg, an important railroad center near Richmond. As the siege continued, Union and Confederate soldiers built complex networks of trenches, tunnels, and artillery emplacements stretching for 40 miles along the eastern edge of Richmond and Petersburg, foreshadowing the devastating trench warfare in France in World War I. Invoking the intense imagery of the Bible, an officer described the continuous artillery barrages and sniping as “living night and day within the ‘valley of the shadow of death.’” The stress was especially great for the outnumbered Confederate troops, who spent months in the muddy, hellish trenches without rotation to the rear.

As time passed, Lincoln and Grant felt pressures of their own. The enormous casualties and military stalemate threatened Lincoln with defeat in the November election. The Republican outlook worsened in July, when Jubal Early’s cavalry raided and burned the Pennsylvania town of Chambersburg and threatened Washington. To punish farmers in the Shenandoah Valley who had aided the Confederate raiders, Grant ordered General Philip H. Sheridan to turn the region into “a barren waste.” Sheridan’s troops conducted a scorched-earth campaign, destroying grain, barns, and gristmills and any other resource useful to the Confederates. These tactics, like Early’s raid, violated the military norms of the day, which treated civilians as noncombatants. Rising desperation and anger were changing the definition of conventional warfare.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did the Emancipation Proclamation and Grant’s appointment as general in chief affect the course of the war?