America’s History: Printed Page 468

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 432

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 416

The Election of 1864 and Sherman’s March

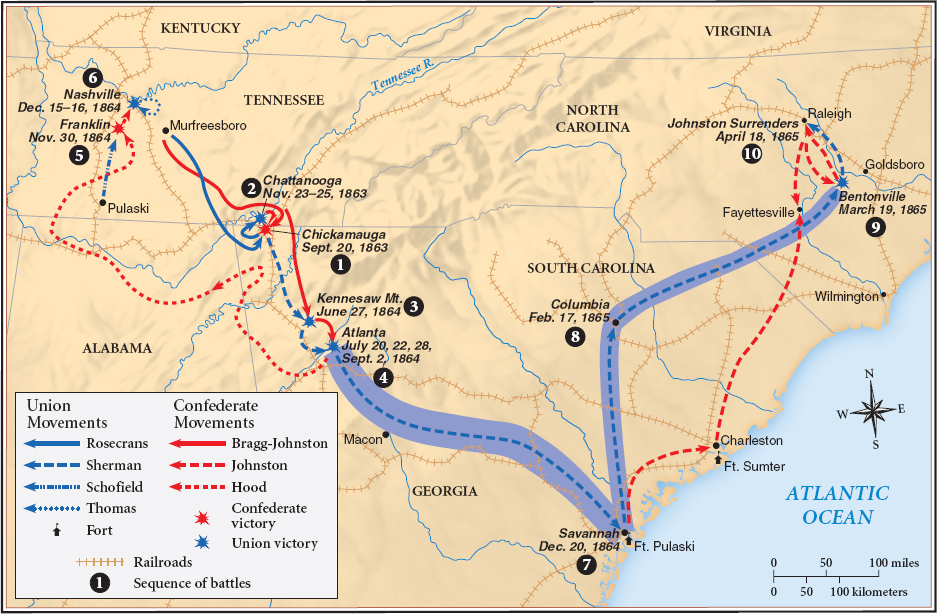

As the siege at Petersburg dragged on, Lincoln’s hopes for reelection depended on General Sherman in Georgia. Sherman’s army of 90,000 men had moved methodically toward Atlanta, a railway hub at the heart of the Confederacy. General Joseph E. Johnson’s Confederate army of 60,000 stood in his way and, in June 1864, inflicted heavy casualties on Sherman’s forces near Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia. By late July, the Union army stood on the northern outskirts of Atlanta, but the next month brought little gain. Like Grant, Sherman seemed bogged down in a hopeless campaign.

The National Union Party Versus the Peace Democrats Meanwhile, the presidential campaign of 1864 was heating up. In June, the Republican Party’s convention rebuffed attempts to prevent Lincoln’s renomination. It endorsed the president’s war strategy, demanded the Confederacy’s unconditional surrender, and called for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery. The delegates likewise embraced Lincoln’s political strategy. To attract border-state and Democratic voters, the Republicans took a new name, the National Union Party, and chose Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee slave owner and Unionist Democrat, as Lincoln’s running mate.

The Democratic Party met in August and nominated General George B. McClellan for president. Lincoln had twice removed McClellan from military commands: first for an excess of caution and then for his opposition to emancipation. Like McClellan, the Democratic delegates rejected emancipation and condemned Lincoln’s repression of domestic dissent, particularly the suspension of habeas corpus and the use of military courts to prosecute civilians. However, they split into two camps over war policy. War Democrats vowed to continue fighting until the rebellion ended, while Peace Democrats called for a “cessation of hostilities” and a constitutional convention to negotiate a peace settlement. Although personally a War Democrat, McClellan promised if elected to recommend to Congress an immediate armistice and a peace convention. Hearing this news, Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens celebrated “the first ray of real light I have seen since the war began.” He predicted that if Atlanta and Richmond held out, Lincoln would be defeated and McClellan would eventually accept an independent Confederacy.

The Fall of Atlanta and Lincoln’s Victory Stephens’s hopes collapsed on September 2, 1864, as Atlanta fell to Sherman’s army. In a stunning move, the Union general pulled his troops from the trenches, swept around the city, and destroyed its rail links to the south. Fearing that Sherman would encircle his army, Confederate general John B. Hood abandoned the city. “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won,” Sherman telegraphed Lincoln, sparking hundred-gun salutes and wild Republican celebration. “We are gaining strength,” Lincoln warned Confederate leaders, “and may, if need be, maintain the contest indefinitely.”

A deep pessimism settled over the Confederacy. Mary Chesnut, a plantation mistress and general’s wife, wrote in her diary, “I felt as if all were dead within me, forever,” and foresaw the end of the Confederacy: “We are going to be wiped off the earth.” Recognizing the dramatically changed military situation, McClellan repudiated the Democratic peace platform. The National Union Party went on the offensive, attacking McClellan’s inconsistency and labeling Peace Democrats as “copperheads” (poisonous snakes) who were hatching treasonous plots. “A man must go for the Union at all hazards,” declared a Republican legislator in Pennsylvania, “if he would entitle himself to be considered a loyal man.”

Lincoln won a clear-cut victory in November. The president received 55 percent of the popular vote and won 212 of 233 electoral votes. Republicans and National Unionists captured 145 of the 185 seats in the House of Representatives and increased their Senate majority to 42 of 52 seats. Many Republicans owed their victory to the votes of Union troops, who wanted to crush the rebellion and end slavery.

Legal emancipation was already under way at the edges of the South. In 1864, Maryland and Missouri amended their constitutions to end slavery, and the three Confederate states occupied by the Union army — Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana — followed suit. Still, abolitionists worried that the Emancipation Proclamation, based legally on the president’s wartime powers, would lose its force at the end of the war. Urged on by Lincoln and the National Equal Rights League, in January 1865 the Republican Congress approved the Thirteenth Amendment, ending slavery, and sent it to the states for ratification. Slavery was nearly dead.

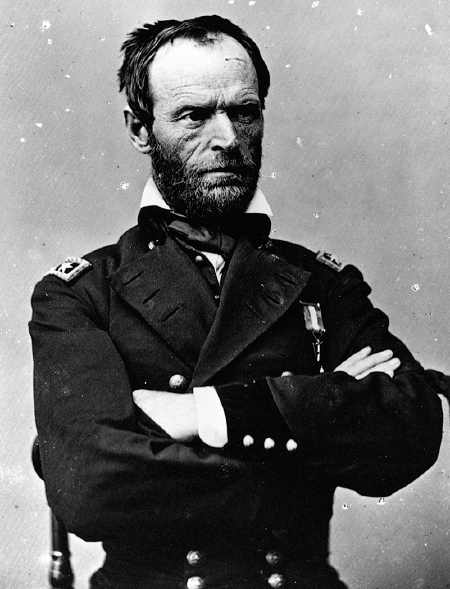

William Tecumseh Sherman: “Hard War” Warrior Thanks to William Tecumseh Sherman, the Confederacy was nearly dead as well. As a young military officer stationed in the South, Sherman sympathized with the planter class and felt that slavery upheld social stability. However, Sherman believed in the Union. Secession meant “anarchy,” he told his southern friends in early 1861: “If war comes … I must fight your people whom I best love.” Serving under Grant, Sherman distinguished himself at Shiloh and Vicksburg. Taking command of the Army of the Tennessee, he developed the philosophy and tactics of “hard war.” “When one nation is at war with another, all the people of one are enemies of the other,” Sherman declared. When Confederate guerrillas fired on a boat carrying Unionist civilians near Randolph, Tennessee, Sherman sent a regiment to destroy the town, asserting, “We are justified in treating all inhabitants as combatants.”

After capturing Atlanta, Sherman advocated a bold strategy. Instead of pursuing the retreating Confederate army northward into Tennessee, he proposed to move south, live off the land, and “cut a swath through to the sea.” To persuade Lincoln and Grant to approve his unconventional plan, Sherman argued that his march would be “a demonstration to the world, foreign and domestic, that we have a power [Jefferson] Davis cannot resist.” The Union general lived up to his pledge. “We are not only fighting hostile armies,” Sherman wrote, “but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war.” He left Atlanta in flames, and during his 300-mile March to the Sea (Map 14.6) his army consumed or demolished everything in its path. A Union veteran wrote, “[We] destroyed all we could not eat, stole their niggers, burned their cotton & gins, spilled their sorghum, burned & twisted their R.Roads and raised Hell generally.” Although Sherman’s army usually did not harm noncombatants who kept to their peaceful business, the havoc so demoralized Confederate soldiers that many deserted their units and returned home (American Voices). When Sherman reached Savannah in mid-December, the city’s 10,000 defenders left without a fight.

Georgia’s African Americans treated Sherman as a savior. “They flock to me, old and young,” he wrote. “[T]hey pray and shout and mix up my name with Moses … as well as ‘Abram Linkom,’ the Great Messiah of ‘Dis Jubilee.’” To provide for the hundreds of blacks now following his army, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, which set aside 400,000 acres of prime rice-growing land for the exclusive use of freedmen. By June 1865, about 40,000 blacks were cultivating “Sherman lands.” Many freedmen believed that the lands were to be theirs forever, belated payment for generations of unpaid labor: “All the land belongs to the Yankees now and they gwine divide it out among de coloured people.”

|

To see more of Sherman’s writing, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

In February 1865, Sherman invaded South Carolina to punish the instigators of nullification and secession. His troops ravaged the countryside as they cut a narrow swath across the state. After capturing South Carolina’s capital, Columbia, they burned the business district, most churches, and the wealthiest residential neighborhoods. “This disappointment to me is extremely bitter,” lamented Jefferson Davis. By March, Sherman had reached North Carolina, ready to link up with Grant and crush Lee’s army.

The Confederate Collapse Grant’s war of attrition in Virginia had already exposed a weakness in the Confederacy: rising class resentment among poor whites. Angered by slave owners’ exemptions from military service and fearing that the Confederacy was doomed, ordinary southern farmers now repudiated the draft. “All they want is to git you … to fight for their infurnal negroes,” grumbled an Alabama hill farmer. More and more soldiers fled their units. “I am now going to work instead of to the war,” vowed David Harris, another backcountry yeoman. By 1865, at least 100,000 men had deserted from Confederate armies, prompting reluctant Confederate leaders to approve the enlistment of black soldiers and promising them freedom. However, the fighting ended too soon to reveal whether any slaves would have fought for the Confederacy.

The symbolic end of the war took place in Virginia. In April 1865, Grant finally gained control of the crucial railroad junction at Petersburg and forced Lee to abandon Richmond. As Lincoln visited the ruins of the Confederate capital, greeted by joyful ex-slaves, Grant cut off Lee’s escape route to North Carolina. On April 9, almost four years to the day after the attack on Fort Sumter, Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. In return for their promise not to fight again, Grant allowed the Confederate officers and men to go home. By late May, all of the secessionist armies and governments had simply melted away (Map 14.7).

The hard and bitter conflict was finally over. Northern armies had preserved the Union and destroyed slavery; many of the South’s factories, railroads, and cities lay in ruins; and its farms and plantations had suffered years of neglect. Almost 260,000 Confederate soldiers had paid for secession with their lives. On the other side, more than 360,000 northerners had died for the Union, and thousands more had been maimed. Was it all worth the price? Delivering his second inaugural address in March 1865 — less than a month before his assassination — Abraham Lincoln could justify the hideous carnage only by alluding to divine providence: “[S]o still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”

What of the war’s effects on society? A New York census taker suggested that the conflict had undermined “autocracy” and had an “equalizing effect.” Slavery was gone from the South, he reflected, and in the North, “military men from the so called ‘lower classes’ now lead society, having been elevated by real merit and valor.” However perceptive these remarks, they ignored the wartime emergence of a new financial aristocracy that would soon preside over what Mark Twain labeled the Gilded Age. Nor was the sectional struggle yet concluded. As the North began to reconstruct the South and the Union, it found those tasks to be almost as hard and bitter as the war itself.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

To what extent were Grant and Sherman’s military strategy and tactics responsible for defeat of the Confederacy?