America’s History: Printed Page 446

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 409

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 395

The Secession Crisis

The Union collapsed first in South Carolina, the home of John C. Calhoun, nullification, and southern rights. Robert Barnwell Rhett and other fire-eaters had demanded secession since the Compromise of 1850, and their goal was now within reach. “Our enemies are about to take possession of the Government,” warned one South Carolinian. Frightened by that prospect, a state convention voted unanimously on December 20, 1860, to dissolve “the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States.”

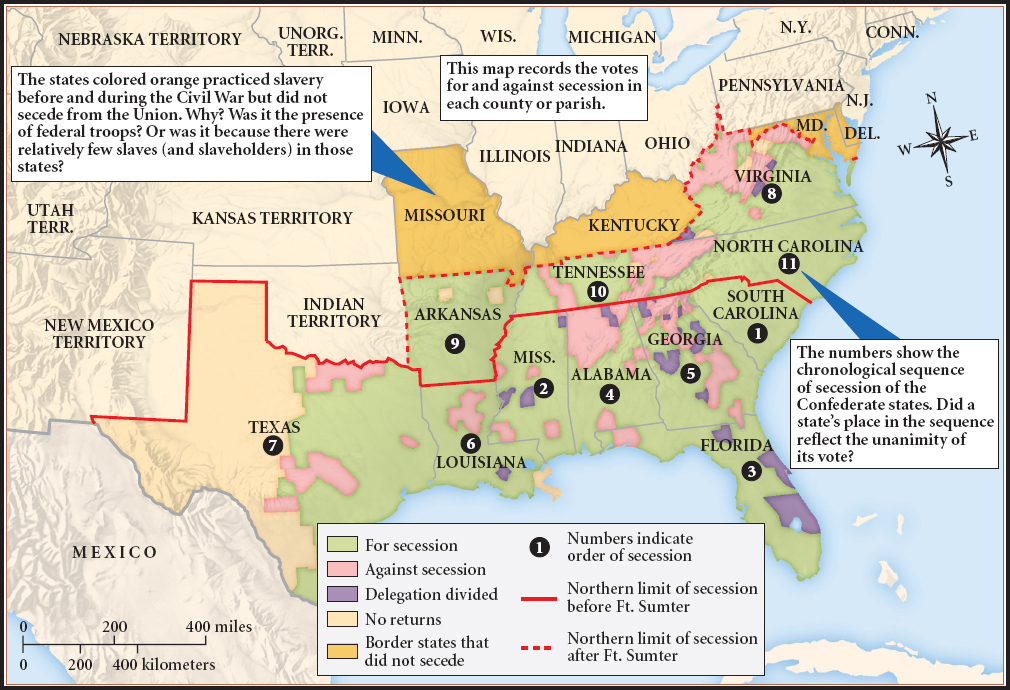

The Lower South Secedes Fire-eaters elsewhere in the Deep South quickly called similar conventions and organized mobs to attack local Union supporters. In early January, white Mississippians joyously enacted a secession ordinance, and Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana quickly followed. Texans soon joined them, ousting Unionist governor Sam Houston and ignoring his warning that “the North … will overwhelm the South” (Map 14.1). In February, the jubilant secessionists met in Montgomery, Alabama, to proclaim a new nation: the Confederate States of America. Adopting a provisional constitution, the delegates named Mississippian Jefferson Davis, a former U.S. senator and secretary of war, as the Confederacy’s president and Georgia congressman Alexander Stephens as vice president.

Secessionist fervor was less intense in the four states of the Middle South (Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas), where there were fewer slaves. White opinion was especially divided in the four border slave states (Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri), where yeomen farmers held greater political power and, from bitter experience as well as the writings of journalist Hilton Helper, knew that all too often “the slaveholders … have hoodwinked you.” Reflecting such sentiments, the legislatures of Virginia and Tennessee refused to join the secessionist movement and urged a compromise.

Meanwhile, the Union government floundered. President Buchanan declared secession illegal but — in line with his states’ rights outlook — claimed that the federal government lacked authority to restore the Union by force. Buchanan’s timidity prompted South Carolina’s new government to demand the surrender of Fort Sumter (a federal garrison in Charleston Harbor) and to cut off its supplies. The president again backed down, refusing to use the navy to supply the fort.

The Crittenden Compromise Instead, the outgoing president urged Congress to find a compromise. The plan proposed by Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky received the most support. The Crittenden Compromise had two parts. The first, which Congress approved, called for a constitutional amendment to protect slavery from federal interference in any state where it already existed. Crittenden’s second provision called for the westward extension of the Missouri Compromise line (36°30' north latitude) to the California border. The provision would ban slavery north of the line and allow bound labor to the south, including any territories “hereafter acquired,” raising the prospect of expansion into Cuba or Central America. Congressional Republicans rejected Crittenden’s second proposal on strict instructions from president-elect Lincoln. With good reason, Lincoln feared it would unleash new imperialist adventures. “I want Cuba,” Senator Albert G. Brown of Mississippi had candidly stated in 1858. “I want Tamaulipas, Potosi, and one or two other Mexican States … for the planting or spreading of slavery.” In 1787, 1821, and 1850, the North and South had resolved their differences over slavery. In 1861, there would be no compromise.

In his March 1861 inaugural address, Lincoln carefully outlined his positions. He promised to safeguard slavery where it existed but vowed to prevent its expansion. Equally important, the Republican president declared that the Union was “perpetual”; consequently, the secession of the Confederate states was illegal. Lincoln asserted his intention to “hold, occupy, and possess” federal property in the seceded states and “to collect duties and imposts” there. If military force was necessary to preserve the Union, Lincoln — like Democrat Andrew Jackson during the nullification crisis — would use it. The choice was the South’s: Return to the Union, or face war.