America’s History: Printed Page 447

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 412

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 398

The Upper South Chooses Sides

The South’s decision came quickly. When Lincoln dispatched an unarmed ship to resupply Fort Sumter, Jefferson Davis and his associates in the Provisional Government of the Confederate States decided to seize the fort. The Confederate forces opened fire on April 12, with ardent fire-eater Edmund Ruffin supposedly firing the first cannon. Two days later, the Union defenders capitulated. On April 15, Lincoln called 75,000 state militiamen into federal service for ninety days to put down an insurrection “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.”

Northerners responded to Lincoln’s call to arms with wild enthusiasm. Asked to provide thirteen regiments of volunteers, Republican governor William Dennison of Ohio sent twenty. Many northern Democrats also lent their support. “Every man must be for the United States or against it,” Democratic leader Stephen Douglas declared. “There can be no neutrals in this war, only patriots — or traitors.” How then could the Democratic Party function as a “loyal opposition,” supporting the Union while challenging certain Republican policies? It would not be an easy task.

Whites in the Middle and Border South now had to choose between the Union and the Confederacy, and their decision was crucial. Those eight states accounted for two-thirds of the whites in the slaveholding states, three-fourths of their industrial production, and well over half of their food. They were home to many of the nation’s best military leaders, including Colonel Robert E. Lee of Virginia, a career officer whom veteran General Winfield Scott recommended to Lincoln to lead the new Union army. Those states were also geographically strategic. Kentucky, with its 500-mile border on the Ohio River, was essential to the movement of troops and supplies. Maryland was vital to the Union’s security because it bordered the nation’s capital on three sides.

The weight of its history as a slave-owning society decided the outcome in Virginia. On April 17, 1861, a convention approved secession by a vote of 88 to 55, with the dissenters concentrated in the state’s yeomen-dominated northwestern counties. Elsewhere, Virginia whites embraced the Confederate cause. “The North was the aggressor,” declared Richmond lawyer William Poague as he enlisted. “The South resisted her invaders.” Refusing General Scott’s offer of the Union command, Robert E. Lee resigned from the U.S. Army. “Save in defense of my native state,” Lee told Scott, “I never desire again to draw my sword.” Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina quickly joined Virginia in the Confederacy.

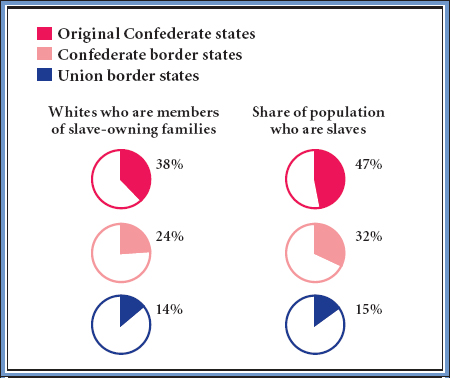

Lincoln moved aggressively to hold strategic areas where relatively few whites owned slaves (Figure 14.1). To secure the railway line connecting Washington to the Ohio River Valley, the president ordered General George B. McClellan to take control of northwestern Virginia. In October 1861, yeomen there voted overwhelmingly to create a breakaway territory, West Virginia. Unwilling to “act like madmen and cut our own throats merely to sustain … a most unwarrantable rebellion,” West Virginia joined the Union in 1863. Unionists also carried the day in Delaware. In Maryland, where slavery was still entrenched, a pro-Confederate mob attacked Massachusetts troops traveling through Baltimore, causing the war’s first combat deaths: four soldiers and twelve civilians. When Maryland secessionists destroyed railroad bridges and telegraph lines, Lincoln ordered Union troops to occupy the state and arrest Confederate sympathizers, including legislators. He released them only in November 1861, after Unionists had secured control of Maryland’s government.

Lincoln was equally energetic in the Mississippi River Valley. To win control of Missouri (and the adjacent Missouri and Upper Mississippi rivers), Lincoln mobilized the state’s German American militia, which strongly opposed slavery. In July, the German Americans defeated a force of Confederate sympathizers commanded by the state’s governor. Despite continuing raids by Confederate guerrilla bands, which included the notorious outlaws Jesse and Frank James, the Union retained control of Missouri.

In Kentucky, where secessionist and Unionist sentiment was evenly balanced, Lincoln moved cautiously. He allowed Kentucky’s thriving trade with the Confederacy to continue until August 1861, when Unionists took over the state government. When the Confederacy responded to the trade cutoff by invading Kentucky in September, Illinois volunteers commanded by Ulysses S. Grant drove them out. Mixing military force with political persuasion, Lincoln had kept four border states (Delaware, Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky) and the northwestern portion of Virginia in the Union.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

How important was the conflict at Fort Sumter, and would the Confederacy — or the Union — have gone to war without it?

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

Per Figure 14.1, was slave ownership in a state the main cause of early secession? What other factors drove the secession movement?