America’s History: Printed Page 449

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 413

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 400

Setting War Objectives and Devising Strategies

Speaking as provisional president of the Confederacy in April 1861, Jefferson Davis identified the Confederates’ cause with that of the Patriots of 1776: like their grandfathers, he said, white southerners were fighting for the “sacred right of self-government.” The Confederacy sought “no conquest, no aggrandizement …; all we ask is to be let alone.” Davis’s renunciation of expansion was probably a calculated short-run policy; after all, the quest to extend slavery into Kansas and Cuba had sparked Lincoln’s election. Still, this decision simplified the Confederacy’s military strategy; it needed only to defend its boundaries to achieve independence. Ignoring strong antislavery sentiment among potential European allies, the Confederate constitution explicitly ruled out gradual emancipation or any other law “denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves.” Indeed, Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens insisted that his nation’s “cornerstone rests upon the great truth that the Negro is not equal to the white man, that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural or normal condition.”

Lincoln responded to Davis in a speech to Congress on July 4, 1861. He portrayed secession as an attack on representative government, America’s great contribution to world history. The issue, Lincoln declared, was “whether a constitutional republic” had the will and the means to “maintain its territorial integrity against a domestic foe.” Determined to crush the rebellion, Lincoln rejected General Winfield Scott’s strategy of peaceful persuasion through economic sanctions and a naval blockade. Instead, he insisted on an aggressive military campaign to restore the Union.

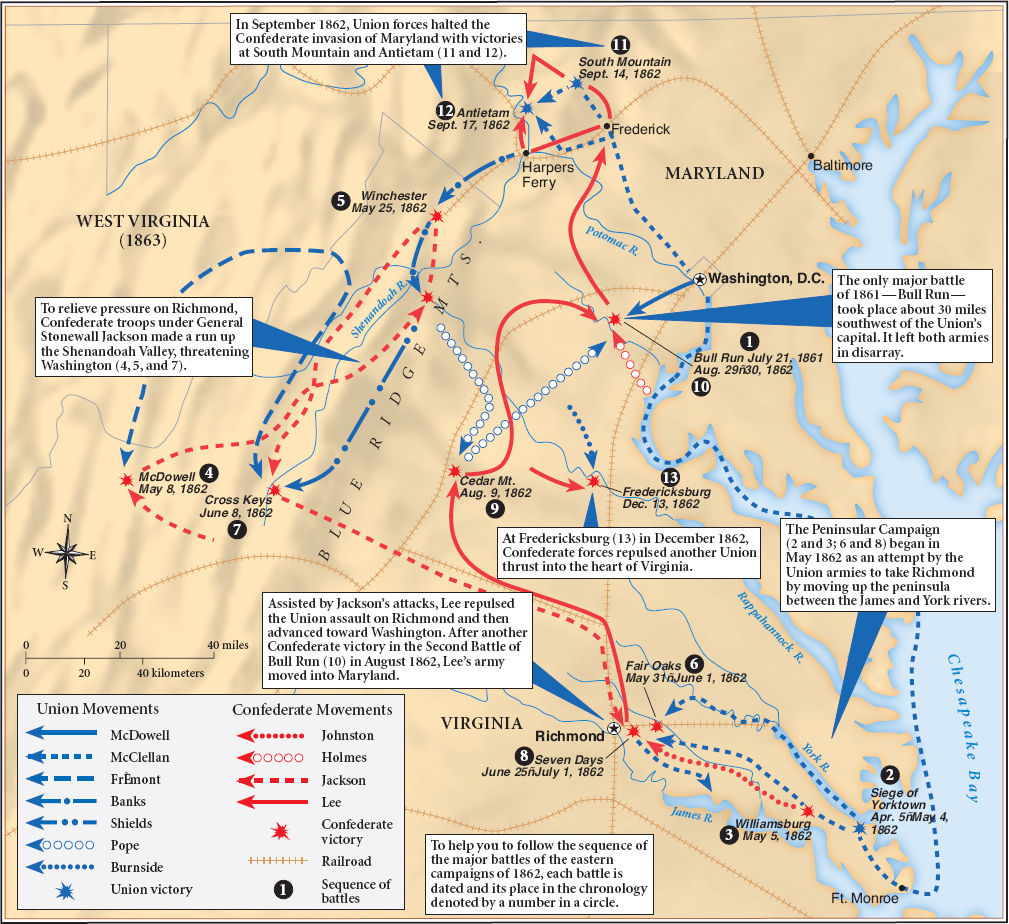

Union Thrusts Toward Richmond Lincoln hoped that a quick strike against the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, would end the rebellion. Many northerners were equally optimistic. “What a picnic,” thought one New York volunteer, “to go down South for three months and clean up the whole business.” So in July 1861, Lincoln ordered General Irvin McDowell’s army of 30,000 men to attack General P. G. T. Beauregard’s force of 20,000 troops at Manassas, a Virginia rail junction 30 miles southwest of Washington. McDowell launched a strong assault near Bull Run, but panic swept his troops when the Confederate soldiers counterattacked, shouting the hair-raising “rebel yell.” “The peculiar corkscrew sensation that it sends down your backbone … can never be told,” one Union veteran wrote. “You have to feel it.” McDowell’s troops — and the many civilians who had come to observe the battle — retreated in disarray to Washington.

The Confederate victory at Bull Run showed the strength of the rebellion. Lincoln replaced McDowell with General George McClellan and enlisted a million men to serve for three years in the new Army of the Potomac. A cautious military engineer, McClellan spent the winter of 1861–1862 training the recruits and launched a major offensive in March 1862. With great logistical skill, the Union general ferried 100,000 troops down the Potomac River to the Chesapeake Bay and landed them on the peninsula between the York and James rivers (Map 14.2). Ignoring Lincoln’s advice to “strike a blow” quickly, McClellan advanced slowly toward Richmond, allowing the Confederates to mount a counterstrike. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson marched a Confederate force rapidly northward through the Shenandoah Valley in western Virginia and threatened Washington. When Lincoln recalled 30,000 troops from McClellan’s army to protect the Union capital, Jackson returned quickly to Richmond to bolster General Robert E. Lee’s army. In late June, Lee launched a ferocious six-day attack that cost 20,000 casualties to the Union’s 10,000. When McClellan failed to exploit the Confederates’ losses, Lincoln ordered a withdrawal and Richmond remained secure.

Lee Moves North: Antietam Hoping for victories that would humiliate Lincoln’s government, Lee went on the offensive. Joining with Jackson in northern Virginia, he routed Union troops in the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 1862) and then struck north through western Maryland. There, he nearly met with disaster. When the Confederate commander divided his force, sending Jackson to capture Harpers Ferry in West Virginia, a copy of Lee’s orders fell into McClellan’s hands. The Union general again failed to exploit his advantage, delaying an attack against Lee’s depleted army, thereby allowing it to secure a strong defensive position west of Antietam Creek, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. Outnumbered 87,000 to 50,000, Lee desperately fought off McClellan’s attacks until Jackson’s troops arrived and saved the Confederates from a major defeat. Appalled by the Union casualties, McClellan allowed Lee to retreat to Virginia.

The fighting at Antietam was savage. A Wisconsin officer described his men “loading and firing with demoniacal fury and shouting and laughing hysterically.” A sunken road — nicknamed Bloody Lane — was filled with Confederate bodies two and three deep, and the advancing Union troops knelt on this “ghastly flooring” to shoot at the retreating Confederates. The battle at Antietam on September 17, 1862, remains the bloodiest single day in U.S. military history. Together, the Confederate and Union dead numbered 4,800 and the wounded 18,500, of whom 3,000 soon died. (By comparison, there were 6,000 American casualties on D-Day, which began the invasion of Nazi-occupied France in World War II.)

In public, Lincoln claimed Antietam as a Union victory; privately, he criticized McClellan for not fighting Lee to the bitter end. A masterful organizer of men and supplies, McClellan refused to risk his troops, fearing that heavy casualties would undermine public support for the war. Lincoln worried more about the danger of a lengthy war. He dismissed McClellan and began a long search for an aggressive commanding general. His first choice, Ambrose E. Burnside, proved to be more daring but less competent than McClellan. In December, after heavy losses in futile attacks against well-entrenched Confederate forces at Fredericksburg, Virginia, Burnside resigned his command, and Lincoln replaced him with Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker. As 1862 ended, Confederates were optimistic: they had won a stalemate in the East.

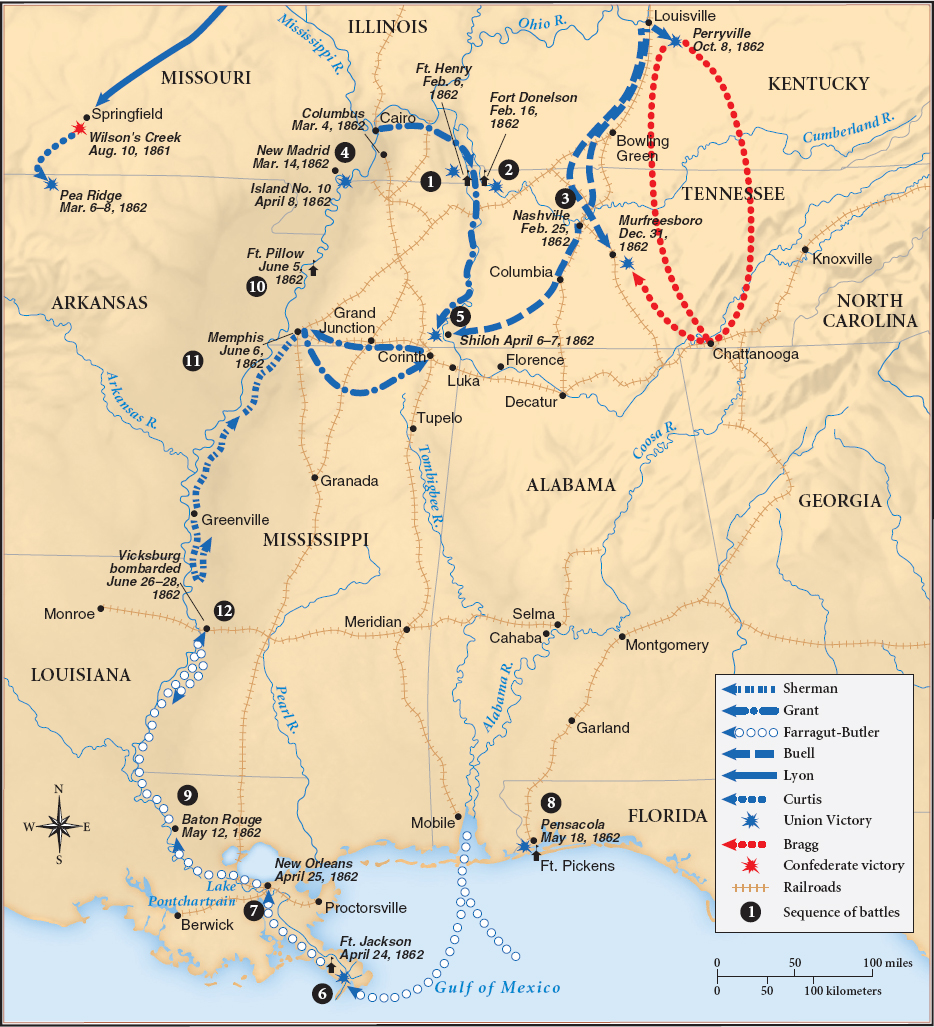

The War in the Mississippi Valley Meanwhile, Union commanders in the Upper South had been more successful (Map 14.3). Their goal was to control the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri rivers, dividing the Confederacy and reducing the mobility of its armies. Because Kentucky did not join the rebellion, the Union already dominated the Ohio River Valley. In February 1862, the Union army used an innovative tactic to take charge of the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers as well. General Ulysses S. Grant used riverboats clad with iron plates to capture Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River and Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. When Grant moved south toward Mississippi to seize critical railroad lines, Confederate troops led by Albert Sidney Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard caught his army by surprise near a small log church at Shiloh, Tennessee. However, Grant relentlessly committed troops and forced a Confederate withdrawal. As the fighting at Shiloh ended on April 7, Grant surveyed a large field “so covered with dead that it would have been possible to walk over the clearing in any direction, stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground.” The cost in lives was horrific, but Lincoln was resolute: “What I want … is generals who will fight battles and win victories.”

Three weeks later, Union naval forces commanded by David G. Farragut struck the Confederacy from the Gulf of Mexico. They captured New Orleans, the South’s financial center and largest city. The Union army also took control of fifteen hundred plantations and 50,000 slaves in the surrounding region, striking a strong blow against slavery. Workers on some plantations looted their owners’ mansions; others refused to labor unless they were paid wages. “[Slavery there] is forever destroyed and worthless,” declared one northern reporter. Union victories had significantly undermined Confederate strength in the Mississippi River Valley.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

In 1861 and 1862, what were the political and military strategies of the Confederate and Union leaders? Which side was the more successful and why?