America’s History: Printed Page 495

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 455

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 437

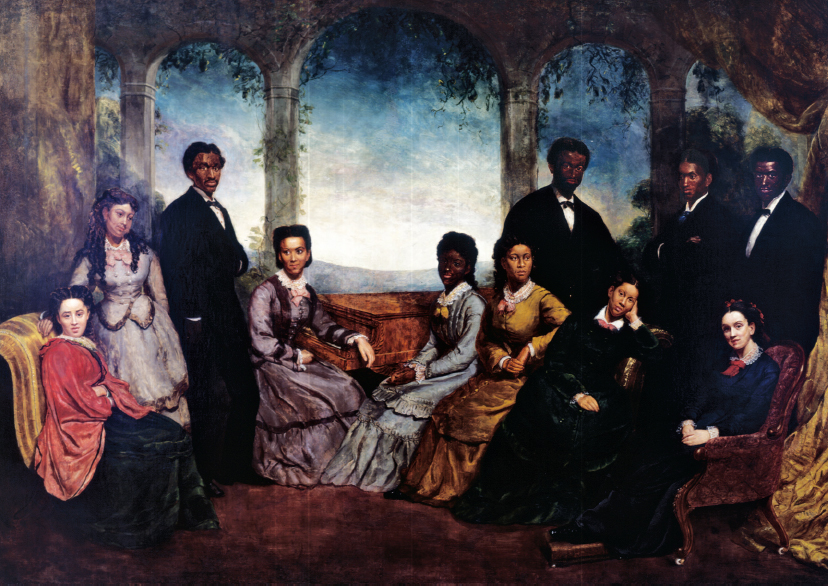

Building Black Communities

In slavery days, African Americans had built networks of religious worship and mutual aid, but these operated largely in secret. After emancipation, southern blacks could engage in open community building. In doing so, they cooperated with northern missionaries and teachers, both black and white, who came to help in the great work of freedom. “Ignorant though they may be, on account of long years of oppression, they exhibit a desire to hear and to learn, that I never imagined,” reported African American minister Reverend James Lynch, who traveled from Maryland to the Deep South. “Every word you say while preaching, they drink down and respond to, with an earnestness that sets your heart all on fire.”

Independent churches quickly became central community institutions, as blacks across the South left white-dominated congregations, where they had sat in segregated balconies, and built churches of their own. These churches joined their counterparts in the North to become national denominations, including, most prominently, the National Baptist Convention and the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Black churches served not only as sites of worship but also as schools, social centers, and meeting halls. Ministers were often political spokesmen as well. As Charles H. Pearce, a black Methodist pastor in Florida, declared, “A man in this State cannot do his whole duty as a minister except he looks out for the political interests of his people.” Religious leaders articulated the special destiny of freedpeople as the new “Children of Israel.”

The flowering of black churches, schools, newspapers, and civic groups was one of the most enduring initiatives of the Reconstruction era. Dedicated teachers and charity leaders embarked on a project of “race uplift” that never ceased thereafter, while black entrepreneurs were proud to build businesses that served their communities. The issue of desegregation — sharing public facilities with whites — was a trickier one. Though some black leaders pressed for desegregation, they were keenly aware of the backlash this was likely to provoke. Others made it clear that they preferred their children to attend all-black schools, especially if they encountered hostile or condescending white teachers and classmates. Many had pragmatic concerns. Asked whether she wanted her boys to attend an integrated school, one woman in New Orleans said no: “I don’t want my children to be pounded by … white boys. I don’t send them to school to fight, I send them to learn.”

At the national level, congressmen wrestled with similar issues as they debated an ambitious civil rights bill championed by Radical Republican senator Charles Sumner. Sumner first introduced his bill in 1870, seeking to enforce, among other things, equal access to schools, public transportation, hotels, and churches. Despite a series of defeats and delays, the bill remained on Capitol Hill for five years. Opponents charged that shared public spaces would lead to race mixing and intermarriage. Some sympathetic Republicans feared a backlash, while others questioned whether, because of the First Amendment, the federal government had the right to regulate churches. On his deathbed in 1874, Sumner exhorted a visitor to remember the civil rights bill: “Don’t let it fail.” In the end, the Senate removed Sumner’s provision for integrated churches, and the House removed the clause requiring integrated schools. But to honor the great Massachusetts abolitionist, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The law required “full and equal” access to jury service and to transportation and public accommodations, irrespective of race. It was the last such act for almost a hundred years — until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

Compare the results of African Americans’ community building with their struggles to obtain better working conditions. What links do you see between these efforts?