America’s History: Printed Page 502

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

The South’s “Lost Cause”

After Reconstruction ended, many white southerners celebrated the Confederacy as a heroic “Lost Cause.” Through organizations such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy, they profoundly influenced the nation’s memories of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction.

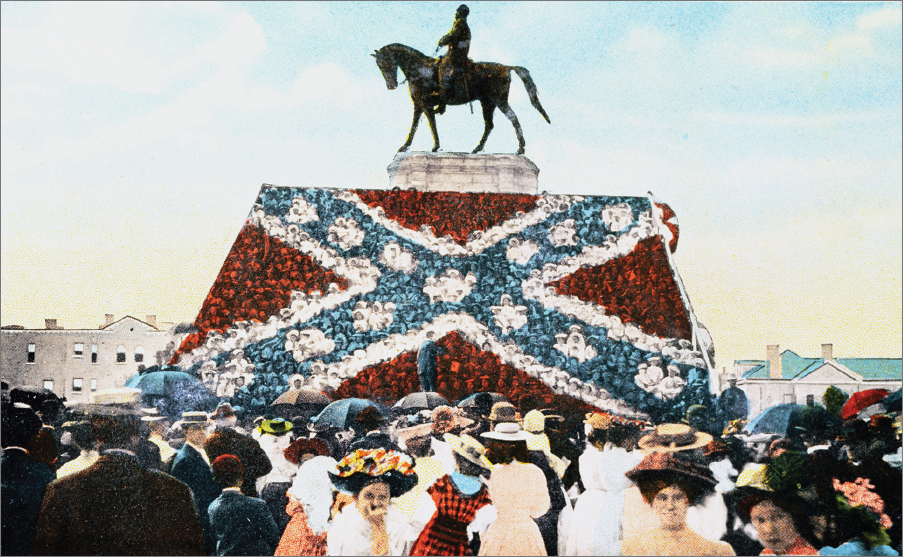

Commemorative postcard of living Confederate flag, Robert E. Lee Monument, Richmond, Virginia, 1907. An estimated 150,000 people gathered in 1890 to dedicate this statue — ten times more than had attended earlier memorial events.

Source: The Library of Virginia.

Source: The Library of Virginia.From the United Daughters of the Confederacy Constitution, 1894. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), founded in 1894, grew in three years to 136 chapters and by the late 1910s counted a membership of 100,000.

The objects of this association are historical, educational, memorial, benevolent, and social: To fulfill the duties of sacred charity to the survivors of the war and those dependent on them; to collect and preserve material for a truthful history of the war; to protect historic places of the Confederacy; to record the part taken by the Southern women … in patient endurance of hardship and patriotic devotion during the struggle; to perpetuate the memory of our Confederate heroes and the glorious cause for which they fought; to cherish the ties of friendship among members of this Association; to endeavor to have used in all Southern schools only such histories as are just and true.

McNeel Marble Co. advertisement in Confederate Veteran magazine, 1905.

To the Daughters of the Confederacy: In regard to that Confederate monument which your Chapter has been talking about and planning for since you first got organized. Why not buy it NOW and have it erected before all the old veterans have answered the final roll call? Why wait and worry about raising funds? Our terms to U.D.C. Chapters are so liberal and our plans for raising funds are so effective as to obviate the necessity of either waiting or worrying. During the last three or four years we have sold Confederate monuments to thirty-seven of your sister Chapters. … Our designs, our prices, our work, our business methods have pleased them, and we can please you. What your sister Chapters have done, you can do. … WRITE TO-DAY.

Confederate veteran’s letter, Confederate Veteran magazine, 1910. An anonymous Georgian who had served in Lee’s army sent the following letter to the veterans’ magazine after attending a reunion in Memphis.

Reunion gatherings are supposed to be for the benefit of the old veterans; but will you show us where the privates, the men who stood the hardships and did the fighting, have any consideration when they get to the city that is expected to entertain them? … [In Memphis, I] stopped at the school building, where there were at least twenty-five or thirty old veterans lying on the ground, and had been there all night. All this while the officers were being banqueted, wined, dined, and quartered in the very best hotels; but the private must shift for himself, stand around on the street, or sit on the curbstone. He must march if he is able, but the officers ride in fine carriages. Pay more attention to the men of the ranks — men who did service! I always go prepared to pay my way; but I do not like to be ignored.

Matthew Page Andrews, The Women of the South in War Times, 1923. Matthew Page Andrews’s The Women of the South in War Times, approved by the UDC, was a popular textbook for decades in schools throughout the South.

The Southern people of the “old regime” have been pictured as engaged primarily in a protracted struggle for the maintenance of negro slavery. … Fighting on behalf of slavery was as far from the minds of these Americans as going to war in order to free the slaves was from the purpose of Abraham Lincoln, whose sole object, frequently expressed by him, was to “preserve the Union.”…

That, in the midst of war, there were almost no instances of arson, murder, or outrage committed by the negroes of the South is an everlasting tribute to the splendid character of the dominant race and their moral uplift of a weaker one. … When these negroes were landed on American shores, almost all were savages taken from the lowest forms of jungle life. It was largely the women of the South who trained these heathen people, molded their characters, and, in the second and third generations, lifted them up a thousand years in the scale of civilization.

Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers, 1902. Susie King Taylor, born in slavery in Georgia in 1848, fled with her uncle during the Civil War and served as a nurse in the Union army.

I read an article, which said the ex-Confederate Daughters had sent a petition to the managers of the local theatres in Tennessee to prohibit the performance of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” claiming it was exaggerated (that is, the treatment of the slaves), and would have a very bad effect on the children who might see the drama. I paused and thought back a few years of the heart-rending scenes I have witnessed. … I remember, as if it were yesterday, seeing droves of negroes going to be sold, and I often went to look at them, and I could hear the auctioneer very plainly from my house, auctioning these poor people off.

Do these Confederate Daughters ever send petitions to prohibit the atrocious lynchings and wholesale murdering and torture of the negro? Do you ever hear of them fearing this would have a bad effect on the children? Which of these two, the drama or the present state of affairs, makes a degrading impression upon the minds of our young generation? In my opinion it is not “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” … It does not seem as if our land is yet civilized.

Sources: (2) Minutes of the Seventh Annual Meeting of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (Nashville, TN.: Press of Foster & Webb, Printers, 1901), 235; (3) Confederate Veteran, 1905; (4) Confederate Veteran, Vol. XVIII (Nashville, TN.: S. A. Cunningham, 1910); (5) Matthew Page Andrews, ed., The Women of the South in War Times (Baltimore: The Norman, Remington Co., 1923), 3–4, 9–10; (6) Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp (Boston: Published by the author, 1902), 65–66.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

What do sources 2 and 3 tell us about the work of local UDC chapters? What does the advertisement suggest about the economy of the postwar South?

Question

What can you infer from these sources about the situation in the South after the Civil War? Why might women have played a particularly important role in memorial associations?

Question

Compare and contrast sources 4 and 6. Who did “Lost Cause” associations serve, and how is this connected to issues of class and race?

Question

How does source 5 depict slaves? Slaveholders? Is this an accurate account of the history of the South, and how does this compare to source 4? What do these different interpretations suggest about the legacy of “Redemption”?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

“Lost Cause” advocates often stated that their work was not political. To what extent was this true, based on the evidence here? What do these documents suggest about the influence of the Lost Cause, and also the limitations and challenges it faced? What do they tell us about the legacies of Reconstruction more broadly?