America’s History: Printed Page 482

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 442

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 426

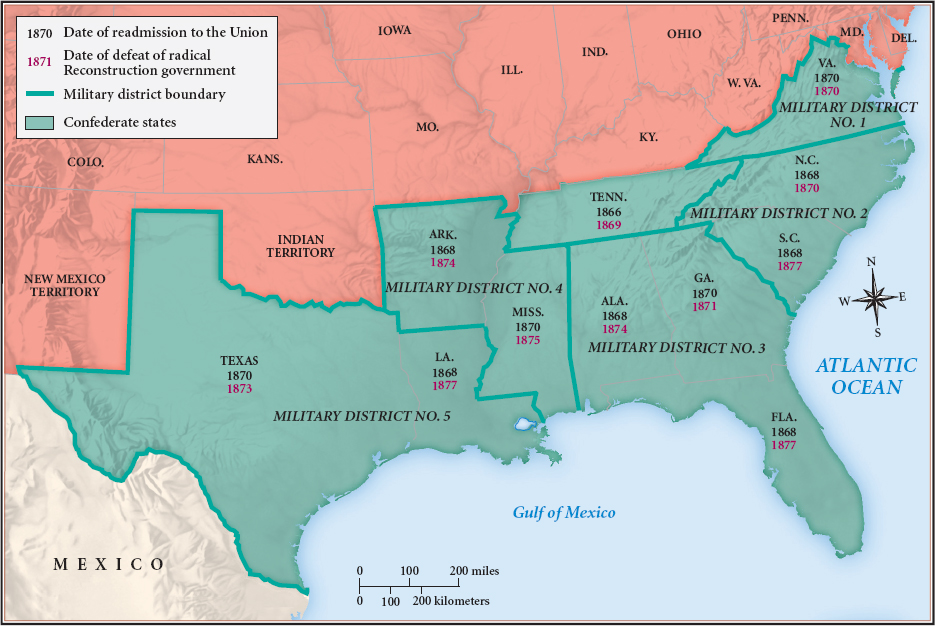

Radical Reconstruction

The Reconstruction Act of 1867, enacted in March, divided the conquered South into five military districts, each under the command of a U.S. general (Map 15.1). To reenter the Union, former Confederate states had to grant the vote to freedmen and deny it to leading ex-Confederates. Each military commander was required to register all eligible adult males, black as well as white; supervise state constitutional conventions; and ensure that new constitutions guaranteed black suffrage. Congress would readmit a state to the Union once these conditions were met and the new state legislature ratified the Fourteenth Amendment. Johnson vetoed the Reconstruction Act, but Congress overrode his veto (Table 15.1).

| Primary Reconstruction Laws and Constitutional Amendments | |

| Law (Date of Congressional Passage) | Key Provisions |

|

Thirteenth Amendment (December 1865*) |

Prohibited slavery |

| Civil Rights Act of 1866 (April 1866) |

Defined citizenship rights of freedmen Authorized federal authorities to bring suit against those who violated those rights |

|

Fourteenth Amendment (June 1866†) |

Established national citizenship for persons born or naturalized in the United States Prohibited the states from depriving citizens of their civil rights or equal protection under the law Reduced state representation in House of Representatives by the percentage of adult male citizens denied the vote |

|

Reconstruction Act of 1867 (March 1867) |

Divided the South into five military districts, each under the command of a Union general Established requirements for readmission of ex-Confederate states to the Union |

|

Tenure of Office Act (March 1867) |

Required Senate consent for removal of any federal official whose appointment had required Senate confirmation |

|

Fifteenth Amendment (February 1869‡) |

Forbade states to deny citizens the right to vote on the grounds of race, color, or “previous condition of servitude” |

|

Ku Klux Klan Act (April 1871) |

Authorized the president to use federal prosecutions and military force to suppress conspiracies to deprive citizens of the right to vote and enjoy the equal protection of the law |

|

*Ratified by three-fourths of all states in December 1865. †Ratified by three-fourths of all states in July 1868. ‡Ratified by three-fourths of all states in March 1870. |

|

The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson In August 1867, Johnson fought back by “suspending” Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, a Radical, and replacing him with Union general Ulysses S. Grant, believing Grant would be a good soldier and follow orders. Johnson, however, had misjudged Grant, who publicly objected to the president’s machinations. When the Senate overruled Stanton’s suspension, Grant — now an open enemy of Johnson — resigned so Stanton could resume his place as secretary of war. On February 21, 1868, Johnson formally dismissed Stanton. The feisty secretary of war responded by barricading himself in his office, precipitating a crisis.

Three days later, for the first time in U.S. history, legislators in the House of Representatives introduced articles of impeachment against the president, employing their constitutional power to charge high federal officials with “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” The House serves, in effect, as the prosecutor in such cases, and the Senate serves as the court. The Republican majority brought eleven counts of misconduct against Johnson, most relating to infringement of the powers of Congress. After an eleven-week trial in the Senate, thirty-five senators voted for conviction — one vote short of the two-thirds majority required. Twelve Democrats and seven Republicans voted for acquittal. The dissenting Republicans felt that removing a president for defying Congress was too damaging to the constitutional system of checks and balances. But despite the president’s acquittal, Congress had shown its power. For the brief months remaining in his term, Johnson was largely irrelevant.

Election of 1868 and the Fifteenth Amendment The impeachment controversy made Grant, already the Union’s greatest war hero, a Republican idol as well. He easily won the party’s presidential nomination in 1868. Although he supported Radical Reconstruction, Grant also urged sectional reconciliation. His Democratic opponent, former New York governor Horatio Seymour, almost declined the nomination because he understood that Democrats could not yet overcome the stain of disloyalty. Grant won by an overwhelming margin, receiving 214 out of 294 electoral votes. Republicans retained two-thirds majorities in both houses of Congress.

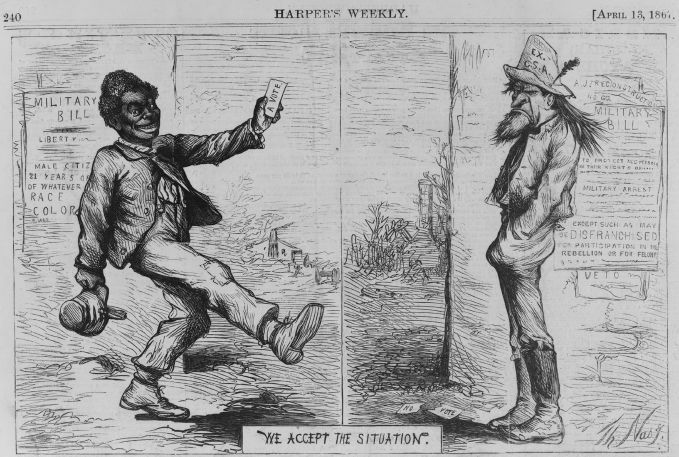

In February 1869, following this smashing victory, Republicans produced the era’s last constitutional amendment, the Fifteenth. It protected male citizens’ right to vote irrespective of race, color, or “previous condition of servitude.” Despite Radical Republicans’ protests, the amendment left room for a poll tax (paid for the privilege of voting) and literacy requirements. Both were concessions to northern and western states that sought such provisions to keep immigrants and the “unworthy” poor from the polls. Congress required the four states remaining under federal control to ratify the measure as a condition for readmission to the Union. A year later, the Fifteenth Amendment became law.

Passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, despite its limitations, was an astonishing feat. Elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere, lawmakers had left emancipated slaves in a condition of semi-citizenship, with no voting rights. But, like almost all Americans, congressional Republicans had extraordinary faith in the power of the vote. Many African Americans agreed. “The colored people of these Southern states have cast their lot with the Government,” declared a delegate to Arkansas’s constitutional convention, “and with the great Republican Party. … The ballot is our only means of protection.” In the election of 1870, hundreds of thousands of African Americans voted across the South, in an atmosphere of collective pride and celebration.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How and why did federal Reconstruction policies evolve between 1865 and 1870?