America’s History: Printed Page 508

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 467

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 450

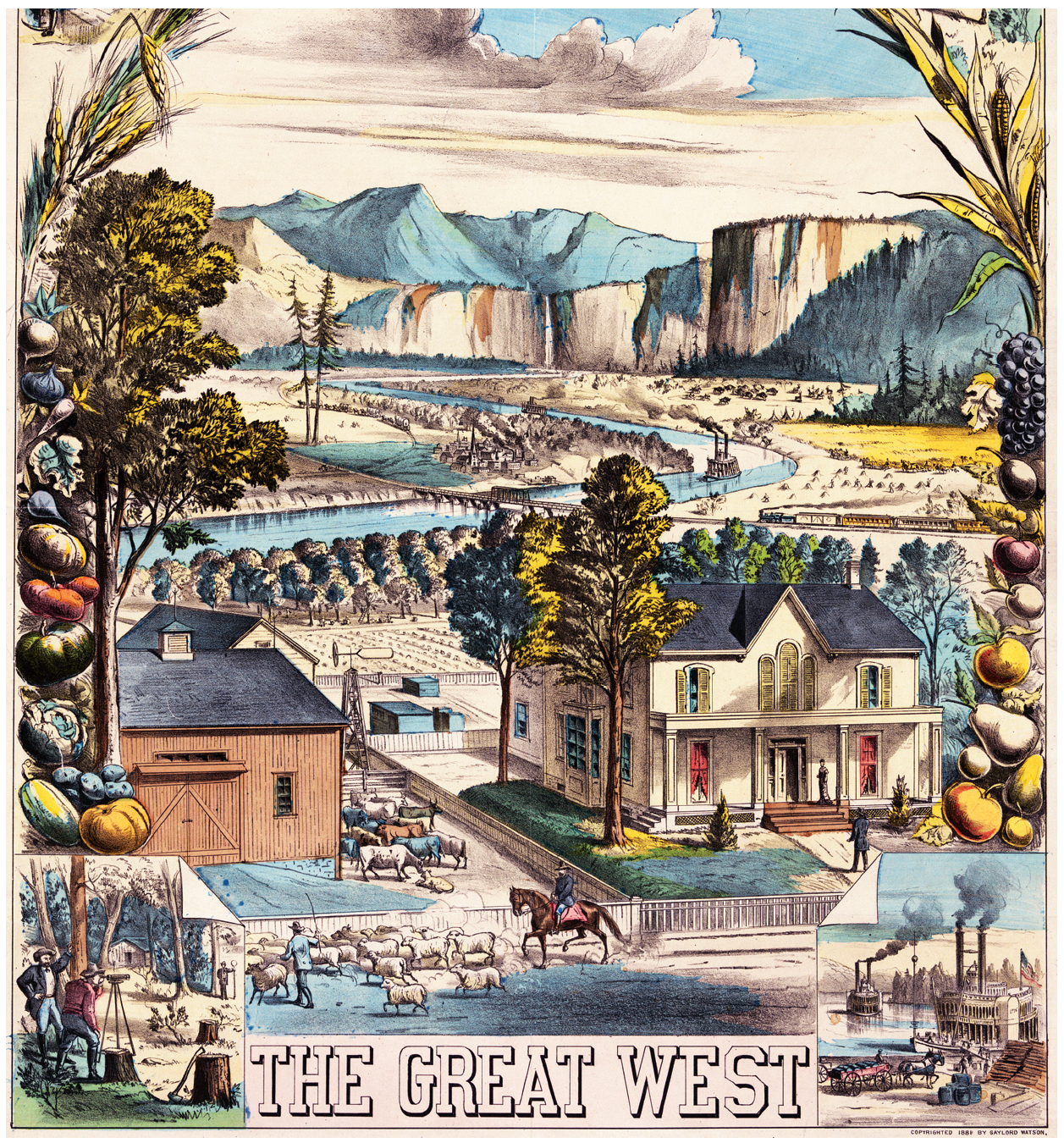

Conquering a Continent

1854–1890

16

CHAPTER

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

How did U.S. policymakers seek to stimulate the economy and integrate the trans-Mississippi west into the nation, and how did this affect people living there?

On May 10, 1869, Americans poured into the streets for a giant party. In big cities, the racket was incredible. Cannons boomed and train whistles shrilled. New York fired a hundred-gun salute at City Hall. Congregations sang anthems, while the less religious gathered in saloons to celebrate with whiskey. Philadelphia’s joyful throngs reminded an observer of the day, four years earlier, when news had arrived of Lee’s surrender. The festivities were prompted by a long-awaited telegraph message: executives of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads had driven a golden spike at Promontory Point, Utah, linking up their lines. Unbroken track now stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific. A journey across North America could be made in less than a week.

The first transcontinental railroad meant jobs and money. San Francisco residents got right to business: after firing a salute, they loaded Japanese tea on a train bound for St. Louis, marking California’s first overland delivery to the East. In coming decades, trade and tourism fueled tremendous growth west of the Mississippi. San Francisco, which in 1860 had handled $7.4 million in imports, increased that figure to $49 million over thirty years. The new railroad would, as one speaker predicted in 1869, “populate our vast territory” and make America “the highway of nations.”

The railroad was also a political triumph. Victorious in the Civil War, Republicans saw themselves as heirs to the American System envisioned by antebellum Whigs. They believed government intervention in the economy was the key to nation building. But unlike Whigs, whose plans had met stiff Democratic opposition, Republicans enjoyed a decade of unparalleled federal power. They used it vigorously: U.S. government spending per person, after skyrocketing in the Civil War, remained well above earlier levels. Republicans believed that national economic integration was the best guarantor of lasting peace. As a New York minister declared, the federally supported transcontinental railroad would “preserve the Union.”

The minister was wrong on one point. He claimed the railroad was a peaceful achievement, in contrast to military battles that had brought “devastation, misery, and woe.” In fact, creating a continental empire caused plenty of woe. Regions west of the Mississippi could only be incorporated if the United States subdued native peoples and established favorable conditions for international investors — often at great domestic cost. And while conquering the West helped make the United States into an industrial power, it also deepened America’s rivalry with European empires and created new patterns of exploitation.