America’s History: Printed Page 516

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 475

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 458

Mining Empires

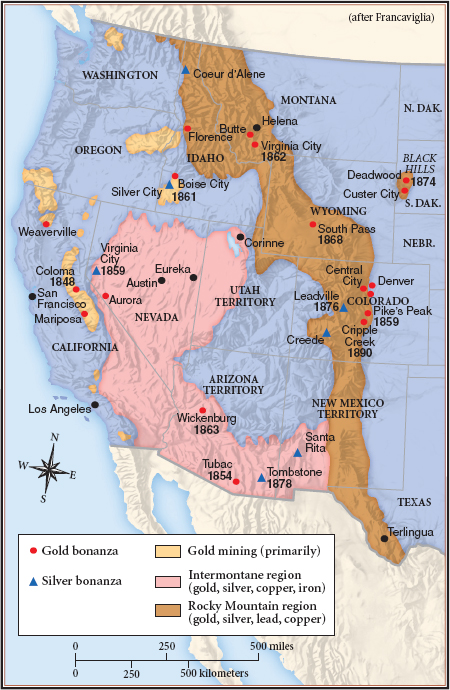

In the late 1850s, as easy pickings in the California gold rush diminished, prospectors scattered in hopes of finding riches elsewhere. They found gold at many sites, including Nevada, the Colorado Rockies, and South Dakota’s Black Hills (Map 16.3). As news of each strike spread, remote areas turned overnight into mob scenes of prospectors, traders, prostitutes, and saloon keepers. At community meetings, white prospectors made their own laws, often using them as an instrument for excluding Mexicans, Chinese, and blacks.

The silver from Nevada’s Comstock Lode, discovered in 1859, built the boomtown of Virginia City, which soon acquired fancy hotels, a Shakespearean theater, and even its own stock exchange. In 1870, a hundred saloons operated in Virginia City, brothels lined D Street, and men outnumbered women 2 to 1. In the 1880s, however, as the Comstock Lode played out, Virginia City suffered the fate of many mining camps: it became a ghost town. What remained was a ravaged landscape with mountains of debris, poisoned water sources, and surrounding lands stripped of timber.

In hopes of encouraging development of western resources, Congress passed the General Mining Act of 1872, which allowed those who discovered minerals on federally owned land to work the claim and keep all the proceeds. (The law — including the $5-per-acre fee for filing a claim — remains in force today.) Americans idealized the notion of the lone, hardy mining prospector with his pan and his mule, but digging into deep veins of underground ore required big money. Consortiums of powerful investors, bringing engineers and advanced equipment, generally extracted the most wealth. This was the case for the New York trading firm Phelps Dodge, which invested in massive copper mines and smelting operations on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. The mines created jobs in new towns like Bisbee and Morenci, Arizona — but with dangerous conditions and low pay, especially for those who received the segregated “Mexican wage.” Anglos, testified one Mexican mine worker, “occupied decorous residences … and had large amounts of money,” while “the Mexican population and its economic condition offered a pathetic contrast.” He protested this affront to “the most elemental principles of justice.”

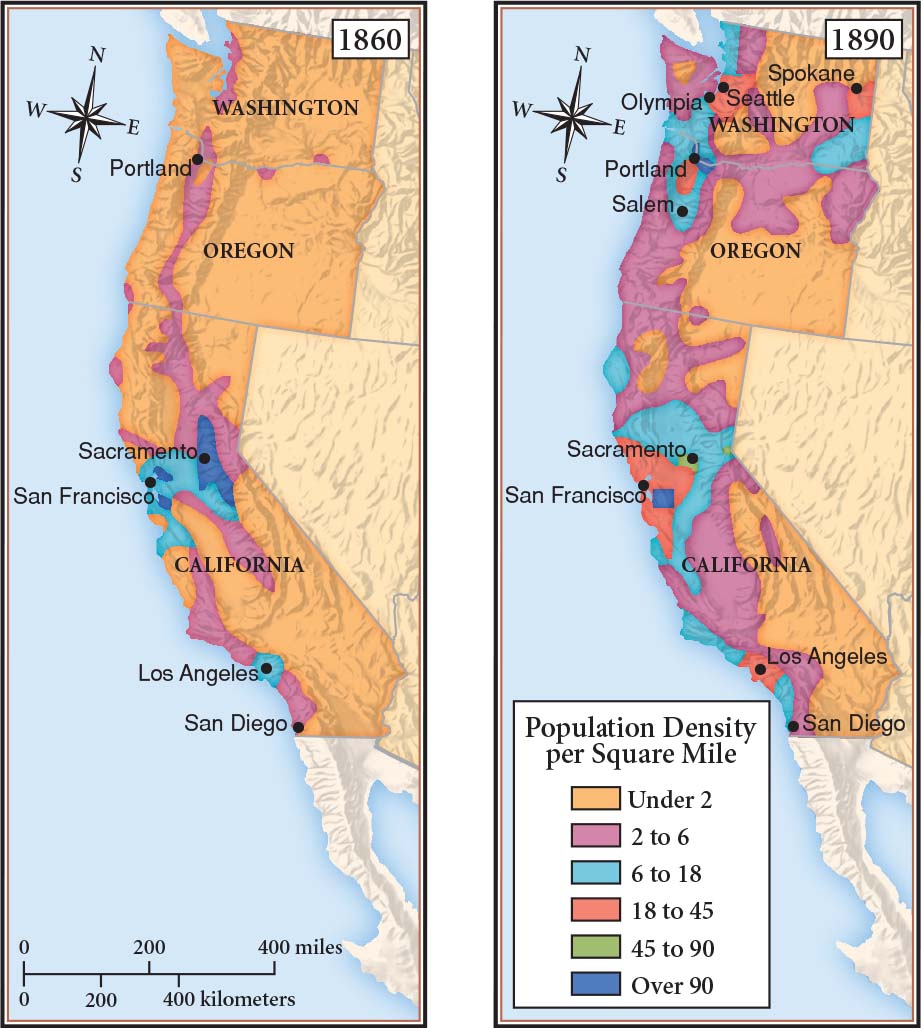

The rise of western mining created an insatiable market for timber and produce from the Pacific Northwest (Map 16.4). Seattle and Portland grew rapidly as supply centers, especially during the great gold rushes of California (after 1849) and the Klondike in Canada’s Yukon Territory (after 1897). Residents of Tacoma, Washington, claimed theirs was the “City of Destiny” when it became the Pacific terminus for the Northern Pacific, the nation’s third transcontinental railroad, in 1887. But rival businessmen in Seattle succeeded in promoting their city as the gateway to Alaska and the Klondike. Seattle, a town with 1,000 residents in 1870, grew over the next forty years to a population of a quarter million.