America’s History: Printed Page 574

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 524

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 507

The Victorians Make the Modern

1880–1917

18

CHAPTER

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

How did the changes wrought by industrialization shape Americans’ identities, beliefs, and culture?

When Philadelphia hosted the 1876 Centennial Exposition, Americans weren’t sure what to expect from their first world’s fair — including what foods exhibitors would offer. One cartoonist humorously proposed that Russians would serve castor oil, Arabs would bring camel’s milk punch, and Germans would offer beer. Reflecting widespread racial prejudices, the cartoon showed Chinese men selling “hashed cat” and “rat pie.” In reality, though, the 1876 Exposition offered only plain lunchrooms and, for the wealthiest visitors, expensive French fare.

By the early twentieth century, American food had undergone a revolution. Visitors to the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 could try food from Scandinavia, India, and the Philippines. Across the United States, Chinese American restaurants flourished as a chop suey craze swept the nation. New Yorkers could sample Hungarian and Syrian cuisine; a San Francisco journalist enthusiastically reviewed local Mexican and Japanese restaurants. Even small-town diners could often find an Italian or German meal.

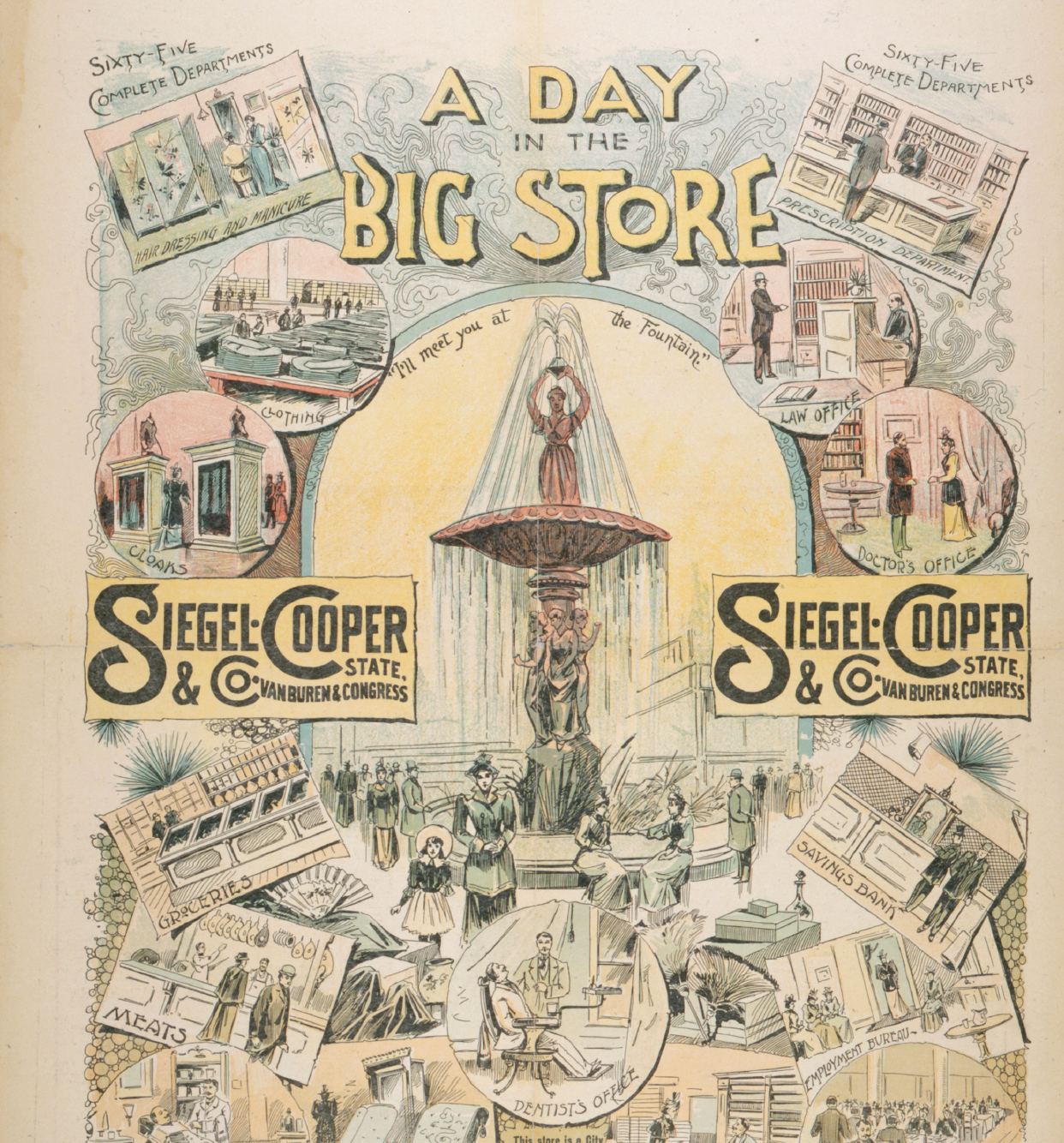

What had happened? Americans had certainly not lost all their prejudices: while plates of chop suey were being gobbled up, laws excluding Chinese immigrants remained firmly in place. Industrialization reshaped class identities, however, and promoted a creative consumer culture. In the great cities, amusement parks and vaudeville theaters catered to industrial workers. Other institutions served middle-class customers who wanted novelty and variety at a reasonable price. A Victorian ethos of self-restraint and moral uplift gave way to expectations of leisure and fun. As African Americans and women claimed a right to public spaces — to shop, dine, and travel freely — they built powerful reform movements. At the same time, the new pressures faced by professional men led to aggressive calls for masculine fitness, exemplified by the rise of sports.

Stunning scientific discoveries — from dinosaur fossils to distant galaxies — also challenged long-held beliefs. Faced with electricity, medical vaccines, and other wonders, Americans celebrated technological solutions to human problems. But while science gained popularity, religion hardly faded. In fact, religious diversity grew, as immigrants brought new faiths and Protestants responded with innovations of their own. Americans found themselves living in a modern world — one in which their grandparents’ beliefs and ways of life no longer seemed to apply. In a market-driven society that claimed to champion individual freedom, Americans took advantage of new ideas while expressing anxiety over the accompanying upheavals and risks.