America’s History: Printed Page 598

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 564

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 529

Religion: Diversity and Innovation

By the turn of the twentieth century, emerging scientific and cultural paradigms posed a significant challenge to religious faith. Some Americans argued that science and modernity would sweep away religion altogether. Contrary to such predictions, American religious practice remained vibrant. Protestants developed creative new responses to the challenges of industrialization, while millions of newcomers built institutions for worship and religious education.

Immigrant Faiths Arriving in the United States in large numbers, Catholics and Jews wrestled with similar questions. To what degree should they adapt to Protestant-dominated American society? Should the education of clergy be changed? Should children attend religious or public schools? What happened if they married outside the faith? Among Catholic leaders, Bishop John Ireland of Minnesota argued that “the principles of the Church are in harmony with the interests of the Republic.” But traditionalists, led by Archbishop Michael A. Corrigan of New York, disagreed. They sought to insulate Catholics from the pluralistic American environment. Indeed, by 1920, almost two million children attended Catholic elementary schools nationwide, and Catholic dioceses operated fifteen hundred high schools. Catholics as well as Jews feared some of the same threats that distressed Protestants: industrial poverty and overwork kept working-class people away from worship services, while new consumer pleasures enticed many of them to go elsewhere.

Faithful immigrant Catholics were anxious to preserve familiar traditions from Europe, and they generally supported the Church’s traditional wing. But they also wanted religious life to express their ethnic identities. Italians, Poles, and other new arrivals wanted separate parishes where they could celebrate their customs, speak their languages, and establish their own parochial schools. When they became numerous enough, they also demanded their own bishops. The Catholic hierarchy, dominated by Irishmen, felt the integrity of the Church was at stake. The demand for ethnic parishes implied local control of church property. With some strain, the Catholic Church managed to satisfy the diverse needs of the immigrant faithful. It met the demand for representation, for example, by appointing immigrant priests as auxiliary bishops within existing dioceses.

In the same decades, many prosperous native-born Jews embraced Reform Judaism, abandoning such religious practices as keeping a kosher kitchen and conducting services in Hebrew. This was not the way of Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe, who arrived in large numbers after the 1880s. Generally much poorer and eager to preserve their own traditions, they founded Orthodox synagogues, often in vacant stores, and practiced Judaism as they had at home.

But in Eastern Europe, Judaism had been an entire way of life, one not easily replicated in a large American city. “The very clothes I wore and the very food I ate had a fatal effect on my religious habits,” confessed the hero of Abraham Cahan’s novel The Rise of David Levinsky (1917). “If you … attempt to bend your religion to the spirit of your surroundings, it breaks. It falls to pieces.” Levinsky shaved off his beard and plunged into the Manhattan clothing business. Orthodox Judaism survived the transition to America, but like other immigrant religions, it had to renounce its claims to some of the faithful.

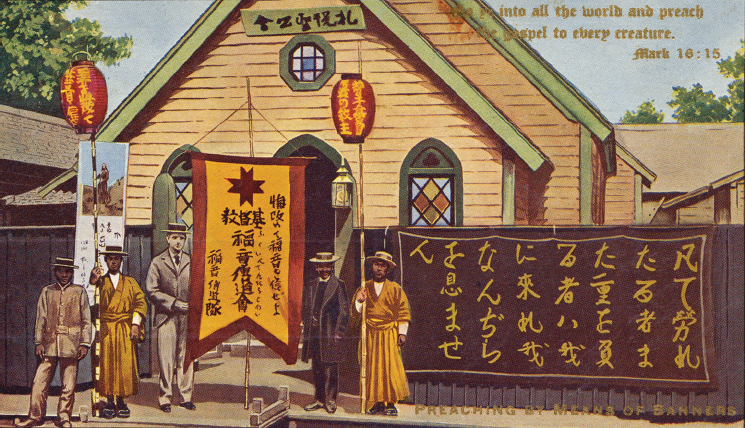

Protestant Innovations One of the era’s dramatic religious developments — facilitated by global steamship and telegraph lines — was the rise of Protestant foreign missions. From a modest start before the Civil War, this movement peaked around 1915, a year when American religious organizations sponsored more than nine thousand overseas missionaries, supported at home by armies of volunteers, including more than three million women. A majority of Protestant missionaries served in Asia, with smaller numbers posted to Africa and the Middle East. Most saw American-style domesticity as a central part of evangelism, and missionary societies sent married couples into the field. Many unmarried women also served overseas as missionary teachers, doctors, and nurses, though almost never as ministers. “American woman,” declared one Christian reformer, has “the exalted privilege of extending over the world those blessed influences, that are to renovate degraded man.”

Protestant missionaries won converts, in part, by providing such modern services as medical care and women’s education. Some missionaries developed deep bonds of respect with the people they served. Others showed considerable condescension toward the “poor heathen,” who in turn bristled at their assumptions (America Compared). One Presbyterian, who found Syrians uninterested in his gospel message, angrily denounced all Muslims as “corrupt and immoral.” By imposing their views of “heathen races” and attacking those who refused to convert, Christian missionaries sometimes ended up justifying Western imperialism.

Chauvinism abroad reflected attitudes that also surfaced at home. Starting in Iowa in 1887, militant Protestants created a powerful political organization, the American Protective Association (APA), which for a brief period in the 1890s counted more than two million members. This virulently nativist group expressed outrage at the existence of separate Catholic schools while demanding, at the same time, that all public school teachers be Protestants. The APA called for a ban on Catholic officeholders, arguing that they were beholden to an “ecclesiastic power” that was “not created and controlled by American citizens.” In its virulent anti-Catholicism and calls for restrictions on immigrants, the APA prefigured the revived Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s.

The APA arose, in part, because Protestants found their dominance challenged. Millions of Americans, especially in the industrial working class, were now Catholics or Jews. Overall, in 1916, Protestants still constituted about 60 percent of Americans affiliated with a religious body. But they faced formidable rivals: the number of practicing Catholics in 1916 — 15.7 million — was greater than the number of Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians combined.

Some Protestants responded to the urban, immigrant challenge by evangelizing among the unchurched. They provided reading rooms, day nurseries, vocational classes, and other services. The goal of renewing religious faith through dedication to justice and social welfare became known as the Social Gospel. Its goals were epitomized by Charles Sheldon’s novel In His Steps (1896), which told the story of a congregation who resolved to live by Christ’s precepts for one year. “If church members were all doing as Jesus would do,” Sheldon asked, “could it remain true that armies of men would walk the streets for jobs, and hundreds of them curse the church, and thousands of them find in the saloon their best friend?”

The Salvation Army, which arrived from Great Britain in 1879, also spread a gospel message among the urban poor, offering assistance that ranged from soup kitchens to shelters for former prostitutes. When all else failed, down-and-outers knew they could count on the Salvation Army, whose bell ringers became a familiar sight on city streets. The group borrowed up-to-date marketing techniques and used the latest business slang in urging its Christian soldiers to “hustle.”

The Salvation Army succeeded, in part, because it managed to bridge an emerging divide between Social Gospel reformers and Protestants who were taking a different theological path. Disturbed by what they saw as rising secularism, conservative ministers and their allies held a series of Bible Conferences at Niagara Falls between 1876 and 1897. The resulting “Niagara Creed” reaffirmed the literal truth of the Bible and the certain damnation of those not born again in Christ. By the 1910s, a network of churches and Bible institutes had emerged from these conferences. They called their movement fundamentalism, based on their belief in the fundamental truth of the Bible.

Fundamentalists and their allies made particularly effective use of revival meetings. Unlike Social Gospel advocates, revivalists said little about poverty or earthly justice, focusing not on the matters of the world, but on heavenly redemption. The pioneer modern evangelist was Dwight L. Moody, a former Chicago shoe salesman and YMCA official who won fame in the 1870s. Eternal life could be had for the asking, Moody promised. His listeners needed only “to come forward and take, TAKE!” Moody’s successor, Billy Sunday, helped bring evangelism into the modern era. More often than his predecessors, Sunday took political stances based on his Protestant beliefs. Condemning the “booze traffic” was his greatest cause. Sunday also denounced unrestricted immigration and labor radicalism. “If I had my way with these ornery wild-eyed Socialists,” he once threatened, “I would stand them up before a firing squad.” Sunday supported some progressive reform causes; he opposed child labor, for example, and advocated voting rights for women. But in other ways, his views anticipated the nativism and antiradicalism that would dominate American politics after World War I.

Billy Sunday, like other noted men of his era, broke free of Victorian practices and asserted his leadership in a masculinized American culture. Not only was he a commanding presence on the stage, but before his conversion he had been a hard-drinking outfielder for the Chicago White Stockings. To advertise his revivals, Sunday often organized local men into baseball teams, then put on his own uniform and played for both sides. Through such feats and the fiery sermons that followed, Sunday offered a model of spiritual inspiration, manly strength, and political engagement. His revivals were thoroughly modern: marketed shrewdly, they provided mass entertainment and the chance to meet a pro baseball player. Like other cultural developments of the industrializing era, Billy Sunday’s popularity showed how Americans often adjusted to modernity: they adapted older beliefs and values, enabling them to endure in new forms.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

How did America’s religious life change in this era, and what prompted those changes?