America’s History: Printed Page 576

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 526

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 509

Consumer Spaces

America’s public spaces — from election polls to saloons and circus shows — had long been boisterous and male-centered. A woman who ventured there without a male chaperone risked damaging her reputation. But the rise of new businesses encouraged change. To attract an eager public, purveyors of consumer culture invited women and families, especially those of the middle class, to linger in department stores and enjoy new amusements.

No one promoted commercial domesticity more successfully than showman P. T. Barnum (1810–1891), who used the country’s expanding rail network to develop his famous traveling circus. Barnum condemned earlier circus managers who had opened their tents to “the rowdy element.” Proclaiming children as his key audience, he created family entertainment for diverse audiences (though in the South, black audiences sat in segregated seats or attended separate shows). He promised middle-class parents that his circus would teach children courage and promote the benefits of exercise. To encourage women’s attendance, Barnum emphasized the respectability and refinement of his female performers.

Department stores also lured middle-class women by offering tearooms, children’s play areas, umbrellas, and clerks to wrap and carry every purchase. Store credit plans enabled well-to-do women to shop without handling money in public. Such tactics succeeded so well that New York’s department store district became known as Ladies’ Mile. Boston department store magnate William Filene called the department store an “Adamless Eden.”

These Edens were for the elite and middle class. Though bargain basements and neighborhood stores served working-class families, big department stores enlisted vagrancy laws and police to discourage the “wrong kind” from entering. Working-class women gained access primarily as clerks, cashiers, and cash girls, who at age twelve or younger served as internal store messengers, carrying orders and change for $1.50 a week. The department store was no Eden for these women, who worked long hours on their feet, often dealing with difficult customers. Nevertheless, many clerks claimed their own privileges as shoppers, making enthusiastic use of employee discounts and battling employers for the right to wear their fashionable purchases while they worked in the store.

In similar ways, class status was marked by the ways technology entered American homes. The rise of electricity, in particular, marked the gap between affluent urban consumers and rural and working-class families. In elite houses, domestic servants began to use — or find themselves replaced by — an array of new devices, from washing machines to vacuum cleaners. When Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876, entrepreneurs introduced the device for business use, but it soon found eager residential customers. Telephones changed etiquette and social relations for middle-class suburban women — while providing their working-class counterparts with new employment options (Thinking Like a Historian).

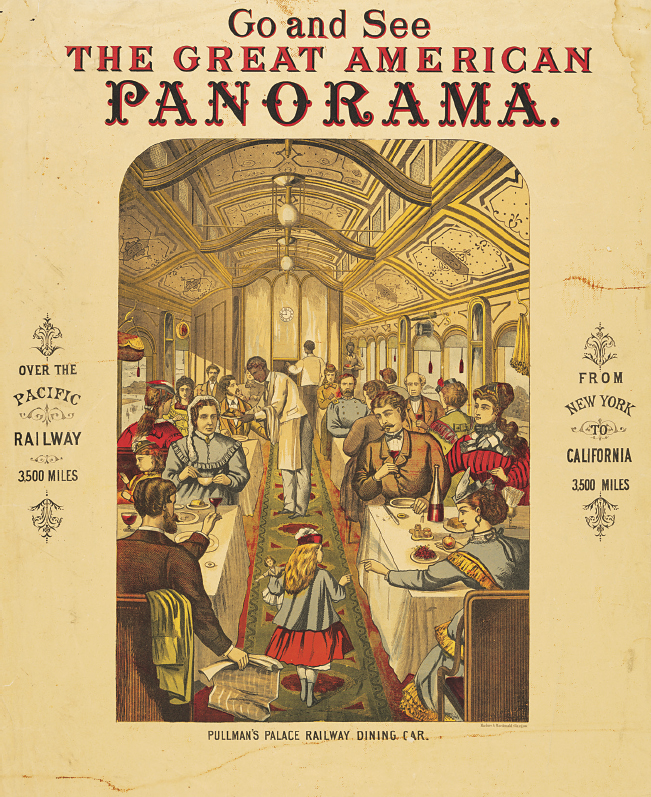

Railroads also reflected the emerging privileges of professional families. Finding prosperous Americans eager for excursions, railroad companies, like department stores, made things comfortable for middle-class women and children. Boston’s South Terminal Station boasted of its modern amenities, including “everything that the traveler needs down to cradles in which the baby may be soothed.” An 1882 tourist guide promised readers that they could live on the Pacific Railroad “with as much true enjoyment as the home drawing room.” Rail cars manufactured by the famous Pullman Company of Chicago set a national standard for taste and elegance. Fitted with rich carpets, upholstery, and woodwork, Pullman cars embodied the growing prosperity of America’s elite, influencing trends in home decor. Part of their appeal was the chance for people of modest means to emulate the rich. An experienced train conductor observed that the wives of grocers, not millionaires, were the ones most likely to “sweep … into a parlor car as if the very carpet ought to feel highly honored by their tread.”

First-class “ladies’ cars” soon became sites of struggle for racial equality. For three decades after the end of the Civil War, state laws and railroad regulations varied, and African Americans often succeeded in securing seats. One reformer noted, however, “There are few ordeals more nerve-wracking than the one which confronts a colored woman when she tries to secure a Pullman reservation in the South and even in some parts of the North.” When they claimed first-class seats, black women often faced confrontations with conductors, resulting in numerous lawsuits in the 1870s and 1880s. Riding the Chesapeake & Ohio line in 1884, young African American journalist Ida B. Wells was told to leave. “I refused,” she wrote later, “saying that the [nearest alternative] car was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies’ car, I proposed to stay.” Wells resisted, but the conductor and a baggage handler threw her bodily off the train. Returning home to Memphis, Wells sued and won in local courts, but Tennessee’s supreme court reversed the ruling.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court settled such issues decisively — but not justly. The case, Plessy v. Ferguson, was brought by civil rights advocates on behalf of Homer Plessy, a New Orleans resident who was one-eighth black. Ordered to leave a first-class car and move to the “colored” car of a Louisiana train, Plessy refused and was arrested. The Court ruled that such segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment as long as blacks had access to accommodations that were “separate but equal” to those of whites. “Separate but equal” was a myth: segregated facilities in the South were flagrantly inferior. Jim Crow segregation laws, named for a stereotyped black character who appeared in minstrel shows, clearly discriminated, but the Court allowed them to stand.

Jim Crow laws applied to public schools and parks and also to emerging commercial spaces — hotels, restaurants, streetcars, trains, and eventually sports stadiums and movie theaters. Placing a national stamp of approval on segregation, the Plessy decision remained in place until 1954, when the Court’s Brown v. Topeka Board of Education ruling finally struck it down. Until then, blacks’ exclusion from first-class “public accommodations” was one of the most painful marks of racism. The Plessy decision, like the rock-bottom wages earned by twelve-year-old girls at Macy’s, showed that consumer culture could be modern and innovative without being politically progressive. Business and consumer culture were shaped by, and themselves shaped, racial and class injustices.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did new consumer practices, arising from industrialization, reshape Americans’ gender, class, and race relationships?