America’s History: Printed Page 580

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 528

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 511

Masculinity and the Rise of Sports

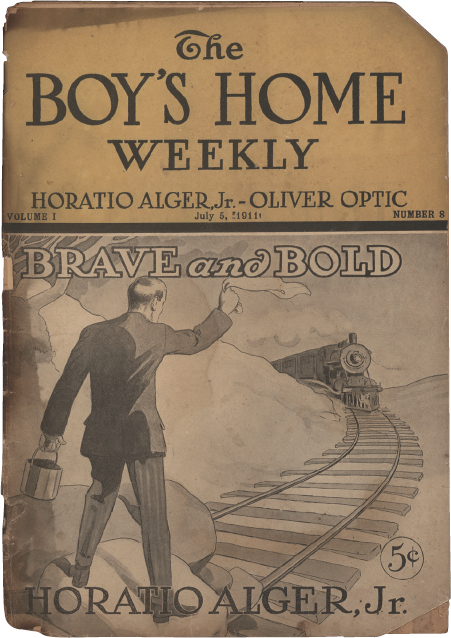

While industrialization spawned public domesticity — a consumer culture that courted affluent women and families — it also changed expectations for men in the workplace. Traditionally, the mark of a successful American man was economic independence: he was his own boss. Now, tens of thousands worked for other men in big companies — and in offices, rather than using their muscles. Would the professional American male, through his concentration on “brain work,” become “weak, effeminate, [and] decaying,” as one editor warned? How could well-to-do men assert their independence if work no longer required them to prove themselves physically? How could they develop toughness and strength? One answer was athletics.

“Muscular Christianity” The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was one of the earliest and most successful promoters of athletic fitness. Introduced in Boston in 1851, the group promoted muscular Christianity, combining evangelism with gyms and athletic facilities where men could make themselves “clean and strong.” Focusing first on white-collar workers, the YMCA developed a substantial industrial program after 1900. Railroad managers and other corporate titans hoped YMCAs would foster a loyal and contented workforce, discouraging labor unrest. Business leaders also relied on sports to build physical and mental discipline and help men adjust their bodies to the demands of the industrial clock. Sports honed men’s competitive spirit, they believed; employer-sponsored teams instilled teamwork and company pride.

Working-class men had their own ideas about sports and leisure, and YMCAs quickly became a site of negotiation. Could workers come to the “Y” to play billiards or cards? Could they smoke? At first, YMCA leaders said no, but to attract working-class men they had to make concessions. As a result, the “Y” became a place where middle-class and working-class customs blended — or existed in uneasy tension. At the same time, YMCA leaders innovated. Searching for winter activities in the 1890s, YMCA instructors invented the new indoor games of basketball and volleyball.

For elite Americans, meanwhile, country clubs flourished; both men and women could enjoy tennis, golf, and swimming facilities as well as social gatherings. By the turn of the century — perhaps because country club women were encroaching on their athletic turf — elite men took up even more aggressive physical sports, including boxing, weightlifting, and martial arts. As early as 1890, future president Theodore Roosevelt argued that such “virile” activities were essential to “maintain and defend this very civilization.” “Most masterful nations,” he claimed, “have shown a strong taste for manly sports.” Roosevelt, son of a wealthy New York family, became one of the first American devotees of jujitsu. During his presidency (1901–1909), he designated a judo room in the White House and hired an expert Japanese instructor. Roosevelt also wrestled and boxed, urging other American men — especially among the elite — to increase their leadership fitness by pursuing the “strenuous life.”

|

To see a longer excerpt of Theodore Roosevelt’s views on sports, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

America’s Game Before the 1860s, the only distinctively American game was Native American lacrosse, and the most popular team sport among European Americans was cricket. After the Civil War, however, team sports became a fundamental part of American manhood, none more successfully than baseball. A derivative of cricket, the game’s formal rules had begun to develop in New York in the 1840s and 1850s. Its popularity spread in military camps during the Civil War. Afterward, the idea that baseball “received its baptism in the bloody days of our Nation’s direst danger,” as one promoter put it, became part of the game’s mythology.

Until the 1870s, most amateur players were clerks and white-collar workers who had leisure to play and the income to buy their own uniforms. Business frowned on baseball and other sports as a waste of time, especially for working-class men. But late-nineteenth-century employers came to see baseball, like other athletic pursuits, as a benefit for workers. It provided fresh air and exercise, kept men out of saloons, and promoted discipline and teamwork. Players on company-sponsored teams, wearing uniforms emblazoned with their employers’ names, began to compete on paid work time. Baseball thus set a pattern for how other American sports developed. Begun among independent craftsmen, it was taken up by elite men anxious to prove their strength and fitness. Well-to-do Americans then decided the sport could benefit the working class.

Big-time professional baseball arose with the launching of the National League in 1876. The league quickly built more than a dozen teams in large cities, from the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers to the Cleveland Spiders. Team owners were, in their own right, profit-minded entrepreneurs who shaped the sport to please consumers. Wooden grandstands soon gave way to concrete and steel stadiums. By 1900, boys collected lithographed cards of their favorite players, and the baseball cap came into fashion. In 1903, the Boston Americans defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates in the first World Series. American men could now adopt a new consumer identity — not as athletes, but as fans.

Rise of the Negro Leagues Baseball stadiums, like first-class rail cars, were sites of racial negotiation and conflict. In the 1880s and 1890s, major league managers hired a few African American players. As late as 1901, the Baltimore Orioles succeeded in signing Charlie Grant, a light-skinned black player from Cincinnati, by renaming him Charlie Tokohoma and claiming he was Cherokee. But as this subterfuge suggested, black players were increasingly barred. A Toledo team received a threatening note before one game in Richmond, Virginia: if their “negro catcher” played, he would be lynched. Toledo put a substitute on the field, and at the end of the season the club terminated the black player’s contract.

Shut out of white leagues, players and fans turned to all-black professional teams, where black men could showcase athletic ability and race pride. Louisiana’s top team, the New Orleans Pinchbacks, pointedly named themselves after the state’s black Reconstruction governor. By the early 1900s, such teams organized into separate Negro Leagues. Though players suffered from erratic pay and rundown ball fields, the leagues thrived until the desegregation of baseball after World War II. In an era of stark discrimination, they celebrated black manhood and talent. “I liked the way their uniform fit, the way they wore their cap,” wrote an admiring fan of the Newark Eagles. “They showed a style in almost everything they did.”

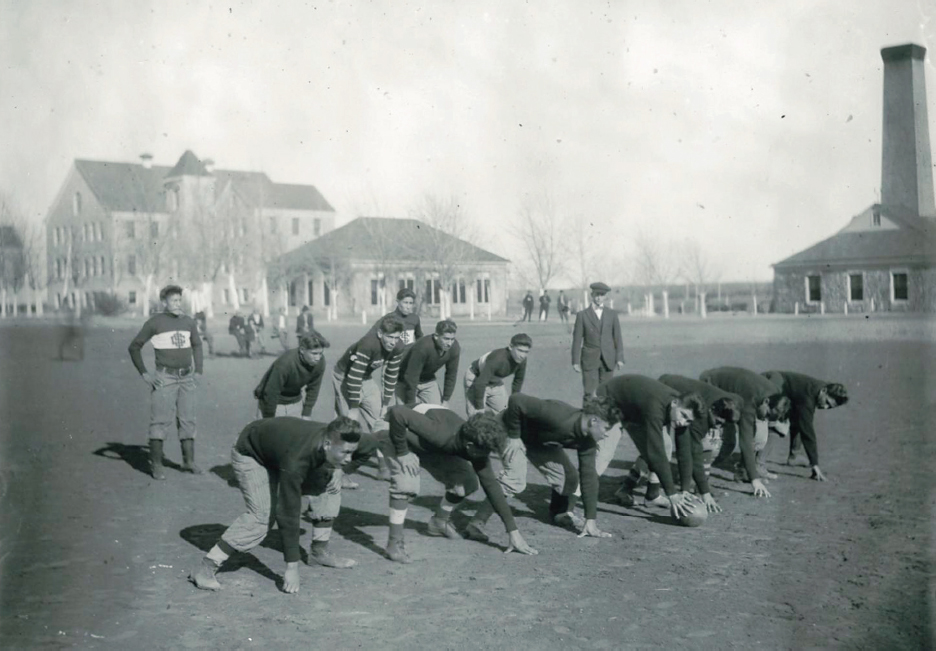

American Football The most controversial sport of the industrializing era was football, which began at elite colleges during the 1880s. The great powerhouse was the Yale team, whose legendary coach Walter Camp went on to become a watch manufacturer. Between 1883 and 1891, under Camp’s direction, Yale scored 4,660 points; its opponents scored 92. Drawing on the workplace model of scientific management, Camp emphasized drill and precision. He and other coaches argued that football offered perfect training for the competitive world of business. The game was violent: six players’ deaths in the 1908 college season provoked a public outcry. Eventually, new rules protected quarterbacks and required coaches to remove injured players from the game. But such measures were adopted grudgingly, with supporters arguing that they ruined football’s benefits in manly training.

Like baseball and the YMCA, football attracted sponsorship from business leaders hoping to divert workers from labor activism. The first professional teams emerged in western Pennsylvania’s steel towns, soon after the defeat of the steelworkers’ union. Carnegie Steel executives organized teams in Homestead and Braddock; the first league appeared during the anthracite coal strike of 1902. Other teams arose in the midwestern industrial heartland. The Indian-Acme Packing Company sponsored the Green Bay Packers; the future Chicago Bears, first known as the Decatur Staleys, were funded by a manufacturer of laundry starch. Like its baseball equivalent, professional football encouraged men to buy in as spectators and fans.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How and why did American sports evolve, and how did athletics soften or sharpen social divisions?