America’s History: Printed Page 625

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 569

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 552

Fighting Dirt and Vice

As early as the 1870s and 1880s, news reporters drew attention to corrupt city governments, the abuse of power by large corporations, and threats to public health. Researcher Helen Campbell reported on tenement conditions in such exposés as Prisoners of Poverty (1887). Making innovative use of the invention of flash photography, Danish-born journalist Jacob Riis included photographs of tenement interiors in his famous 1890 book, How the Other Half Lives. Riis had a profound influence on Theodore Roosevelt when the future president served as New York City’s police commissioner. Roosevelt asked Riis to lead him on tours around the tenements, to help him better understand the problems of poverty, disease, and crime.

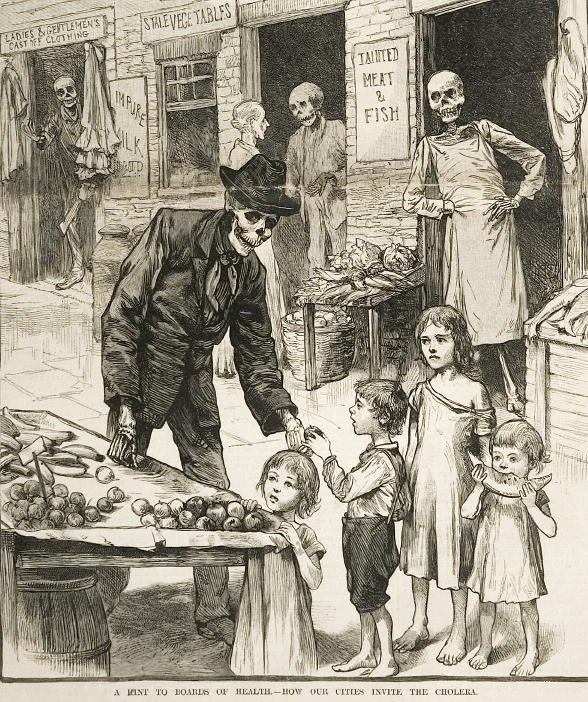

Cleaning Up Urban Environments One of the most urgent problems of the big city was disease. In the late nineteenth century, scientists in Europe came to understand the role of germs and bacteria. Though researchers could not yet cure epidemic diseases, they could recommend effective measures for prevention. Following up on New York City’s victory against cholera in 1866 — when government officials instituted an effective quarantine and prevented large numbers of deaths — city and state officials began to champion more public health projects. With a major clean-water initiative for its industrial cities in the late nineteenth century, Massachusetts demonstrated that it could largely eliminate typhoid fever. After a horrific yellow fever epidemic in 1878 that killed perhaps 12 percent of its population, Memphis, Tennessee, invested in state-of-the-art sewage and drainage. Though the new system did not eliminate yellow fever, it unexpectedly cut death rates from typhoid and cholera, as well as infant deaths from water-borne disease. Other cities followed suit. By 1913, a nationwide survey of 198 cities found that they were spending an average of $1.28 per resident for sanitation and other health measures.

The public health movement became one of the era’s most visible and influential reforms. In cities, the impact of pollution was obvious. Children played on piles of garbage, breathed toxic air, and consumed poisoned food, milk, and water. Infant mortality rates were shocking: in the early 1900s, a baby born to a Slavic woman in an American city had a 1 in 3 chance of dying in infancy. Outraged, reformers mobilized to demand safe water and better garbage collection. Hygiene reformers taught hand-washing and other techniques to fight the spread of tuberculosis.

Americans worked in other ways to make industrial cities healthier and more beautiful to live in. Many municipalities adopted smoke-abatement laws, though they had limited success with enforcement until the post–World War I adoption of natural gas, which burned cleaner than coal. Recreation also received attention. Even before the Civil War, urban planners had established sanctuaries like New York’s Central Park, where city people could stroll, rest, and contemplate natural landscapes. By the turn of the twentieth century, the “City Beautiful” movement arose to advocate more and better urban park spaces. Though most parks still featured flower gardens and tree-lined paths, they also made room for skating rinks, tennis courts, baseball fields, and swimming pools. Many included play areas with swing sets and seesaws, promoted by the National Playground Association as a way to keep urban children safe and healthy.

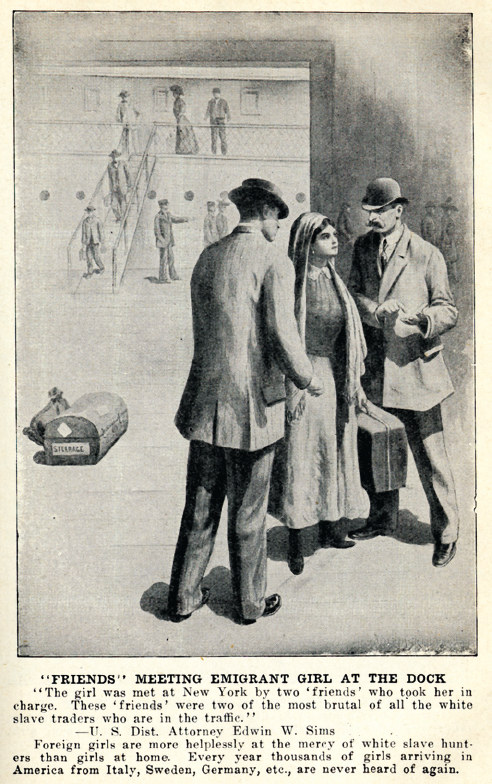

Closing Red Light Districts Distressed by the commercialization of sex, reformers also launched a campaign against urban prostitution. They warned, in dramatic language, of the threat of white slavery, alleging (in spite of considerable evidence to the contrary) that large numbers of young white women were being kidnapped and forced into prostitution. In The City’s Perils (1910), author Leona Prall Groetzinger wrote that young women arrived from the countryside “burning with high hope and filled with great resolve, but the remorseless city takes them, grinds them, crushes them, and at last deposits them in unknown graves.”

Practical investigators found a more complex reality: women entered prostitution as a result of many factors, including low-wage jobs, economic desperation, abandonment, and often sexual and domestic abuse. Women who bore a child out of wedlock were often shunned by their families and forced into prostitution. Some working women and even housewives undertook casual prostitution to make ends meet. For decades, female reformers had tried to “rescue” such women and retrain them for more respectable employments, such as sewing. Results were, at best, mixed. Efforts to curb demand — that is, to focus on arresting and punishing men who employed prostitutes — proved unpopular with voters.

Nonetheless, with public concern mounting over “white slavery” and the payoffs machine bosses exacted from brothel keepers, many cities appointed vice commissions in the early twentieth century. A wave of brothel closings crested between 1909 and 1912, as police shut down red light districts in cities nationwide. Meanwhile, Congress passed the Mann Act (1910) to prohibit the transportation of prostitutes across state lines.

The crusade against prostitution accomplished its main goal, closing brothels, but in the long term it worsened the conditions under which many prostitutes worked. Though conditions in some brothels were horrific, sex workers who catered to wealthy clients made high wages and were relatively protected by madams, many of whom set strict rules for clients and provided medical care for their workers. In the wake of brothel closings, such women lost control of the prostitution business. Instead, almost all sex workers became “streetwalkers” or “call girls,” more vulnerable to violence and often earning lower wages than they had before the antiprostitution crusade began.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What prompted the rise of urban environmental and antiprostitution campaigns?