America’s History: Printed Page 6

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 6

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 6

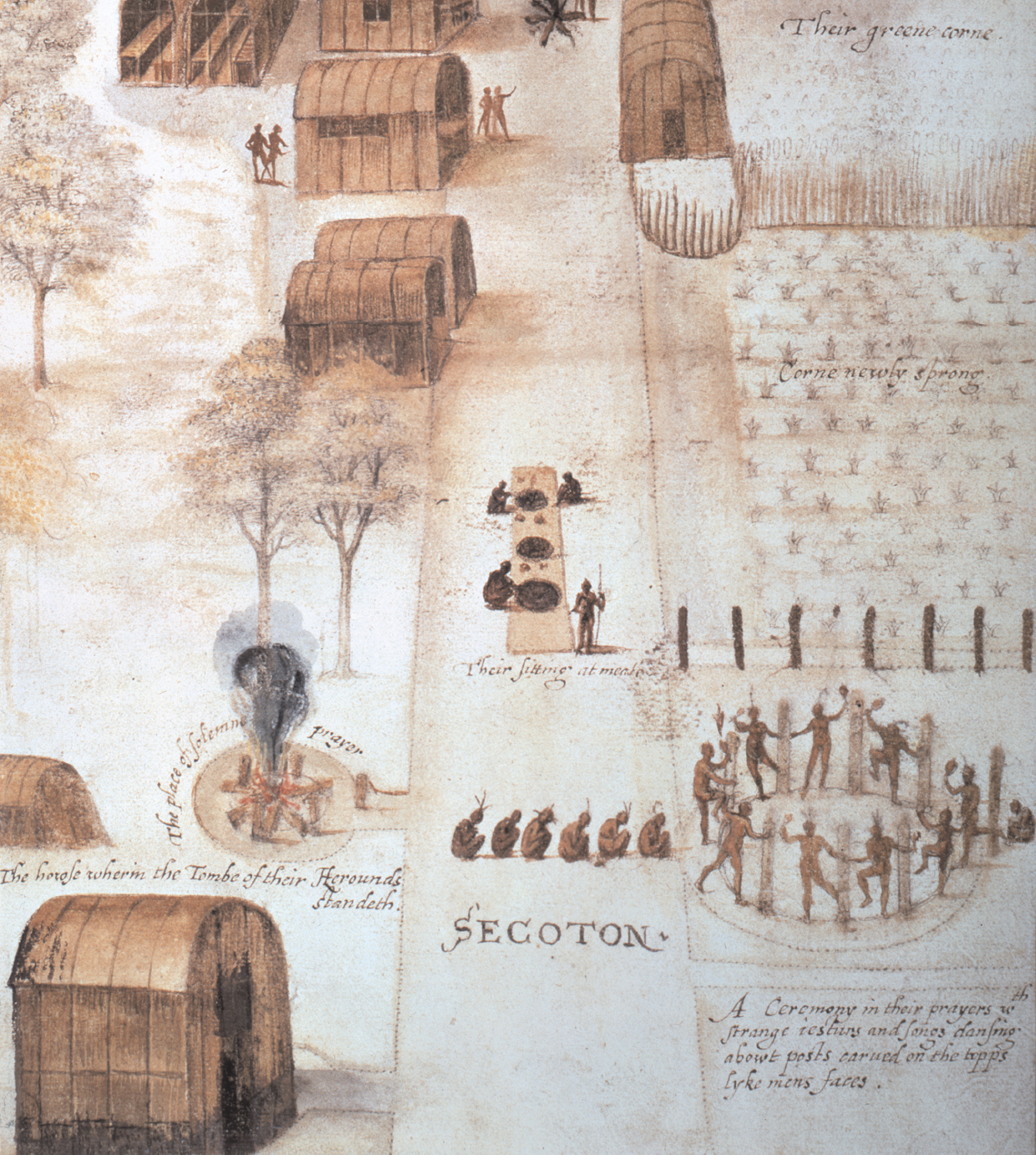

Colliding Worlds

1450–1600

1

CHAPTER

IDENTIFY THE BIG IDEA

How did the political, economic, and religious systems of Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans compare, and how did things change as a result of contacts among them?

In April 1493, a Genoese sailor of humble origins appeared at the court of Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon along with six Caribbean natives, numerous colorful parrots, and “samples of finest gold, and many other things never before seen or heard tell of in Spain.” The sailor was Christopher Columbus, just returned from his first voyage into the Atlantic. He and his party entered Barcelona’s fortress in a solemn procession. The monarchs stood to greet Columbus; he knelt to kiss their hands. They talked for an hour and then adjourned to the royal chapel for a ceremony of thanksgiving. Columbus, now bearing the official title Admiral of the Ocean Sea, remained at court for more than a month. The highlight of his stay was the baptism of the six natives, whom Columbus called Indians because he mistakenly believed he had sailed westward all the way to Asia.

•

In the spring of 1540, the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto met the Lady of Cofachiqui, ruler of a large Native American province in present-day South Carolina. Though an epidemic had carried away many of her people, the lady of the province offered the Spanish expedition as much corn, and as many pearls, as it could carry. As she spoke to de Soto, she unwound “a great rope of pearls as large as hazelnuts” and handed them to the Spaniard; in return he gave her a gold ring set with a ruby. De Soto and his men then visited the temples of Cofachiqui, which were guarded by carved statues and held storehouses of weapons and chest upon chest of pearls. After loading their horses with corn and pearls, they continued on their way.

•

A Portuguese traveler named Duarte Lopez visited the African kingdom of Kongo in 1578. “The men and women are black,” he reported, “some approaching olive colour, with black curly hair, and others with red. The men are of middle height, and, excepting the black skin, are like the Portuguese.” The royal city of Kongo sat on a high plain that was “entirely cultivated,” with a population of more than 100,000. The city included a separate commercial district, a mile around, where Portuguese traders acquired ivory, wax, honey, palm oil, and slaves from the Kongolese.

•

Three glimpses of three lost worlds. Soon these peoples would be transforming one another’s societies, often through conflict and exploitation. But at the moment they first met, Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans stood on roughly equal terms. Even a hundred years after Columbus’s discovery of the Americas, no one could have foreseen the shape that their interactions would take in the generations to come. To begin, we need to understand the three worlds as distinct places, each home to unique societies and cultures.