America’s History: Printed Page 20

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 19

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 19

Myths, Religions, and Holy Warriors

The oldest European religious beliefs drew on a form of animism similar to that of Native Americans, which held that the natural world — the sun, wind, stones, animals — was animated by spiritual forces. As in North America, such beliefs led ancient European peoples to develop localized cults of knowledge and spiritual practice. Wise men and women developed rituals to protect their communities, ensure abundant harvests, heal illnesses, and bring misfortunes to their enemies.

The pagan traditions of Greece and Rome overlaid animism with elaborate myths about gods interacting directly with the affairs of human beings. As the Roman Empire expanded, it built temples to its gods wherever it planted new settlements. Thus peoples throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Near East were exposed to the Roman pantheon. Soon the teachings of Christianity began to flow in these same channels.

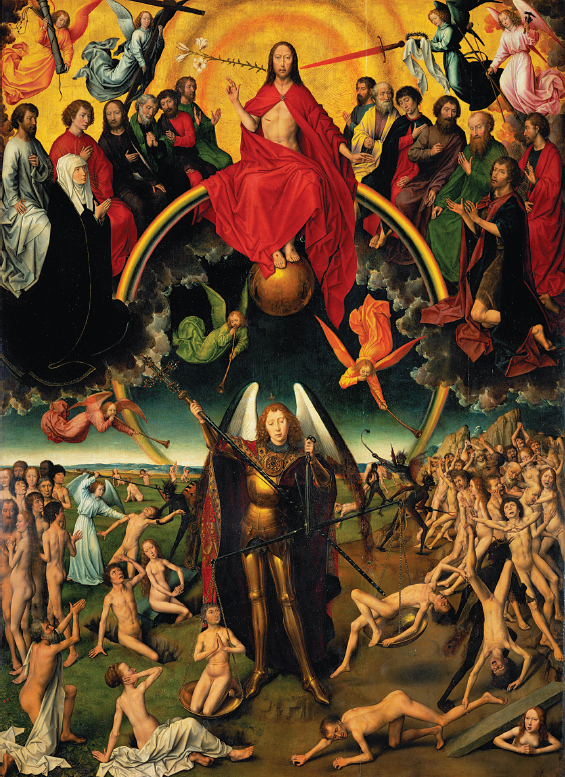

The Rise of Christianity Christianity, which grew out of Jewish monotheism (the belief in one god), held that Jesus Christ was himself divine. As an institution, Christianity benefitted enormously from the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine in A.D. 312. Prior to that time, Christians were an underground sect at odds with the Roman Empire. After Constantine’s conversion, Christianity became Rome’s official religion, temples were abandoned or remade into churches, and noblemen who hoped to retain their influence converted to the new state religion. For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church was the great unifying institution in Western Europe. The pope in Rome headed a vast hierarchy of cardinals, bishops, and priests. Catholic theologians preserved Latin, the language of classical scholarship, and imbued kingship with divine power. Christian dogma provided a common understanding of God and human history, and the authority of the Church buttressed state institutions. Every village had a church, and holy shrines served as points of contact with the sacred world. Often those shrines had their origins in older, animist practices, now largely forgotten and replaced with Christian ritual.

Christian doctrine penetrated deeply into the everyday lives of peasants. While animist traditions held that spiritual forces were alive in the natural world, Christian priests taught that the natural world was flawed and fallen. Spiritual power came from outside nature, from a supernatural God who had sent his divine son, Jesus Christ, into the world to save humanity from its sins. The Christian Church devised a religious calendar that transformed animist festivals into holy days. The winter solstice, which had for millennia marked the return of the sun, became the feast of Christmas.

The Church also taught that Satan, a wicked supernatural being, was constantly challenging God by tempting people to sin. People who spread heresies — doctrines that were inconsistent with the teachings of the Church — were seen as the tools of Satan, and suppressing false doctrines became an obligation of Christian rulers.

The Crusades In their work suppressing false doctrines, Christian rulers were also obliged to combat Islam, the religion whose followers considered Muhammad to be God’s last prophet. Islam’s reach expanded until it threatened European Christendom. Following the death of Muhammad in A.D. 632, the newly converted Arab peoples of North Africa used force and fervor to spread the Muslim faith into sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Indonesia, as well as deep into Spain and the Balkan regions of Europe. Between A.D. 1096 and 1291, Christian armies undertook a series of Crusades to reverse the Muslim advance in Europe and win back the holy lands where Christ had lived. Under the banner of the pope and led by Europe’s Christian monarchs, crusading armies aroused great waves of popular piety as they marched off to combat. New orders of knights, like the Knights Templar and the Teutonic Knights, were created to support them.

The crusaders had some military successes, but their most profound impact was on European society. Religious warfare intensified Europe’s Christian identity and prompted the persecution of Jews and their expulsion from many European countries. The Crusades also introduced Western European merchants to the trade routes that stretched from Constantinople to China along the Silk Road and from the Mediterranean Sea through the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean. And crusaders encountered sugar for the first time. Returning soldiers brought it back from the Middle East, and as Europeans began to conquer territory in the eastern Mediterranean, they experimented with raising it themselves. These early experiments with sugar would have a profound impact on European enterprise in the Americas — and European involvement with the African slave trade — in the centuries to come. By 1450, Western Europe remained relatively isolated from the centers of civilization in Eurasia and Africa, but the Crusades and the rise of Italian merchant houses had introduced it to a wider world.

The Reformation In 1517, Martin Luther, a German monk and professor at the university in Wittenberg, took up the cause of reform in the Catholic Church. Luther’s Ninety-five Theses condemned the Church for many corrupt practices. More radically, Luther downplayed the role of the clergy as mediators between God and believers and said that Christians must look to the Bible, not to the Church, as the ultimate authority in matters of faith. So that every literate German could read the Bible, previously available only in Latin, Luther translated it into German.

Meanwhile, in Geneva, Switzerland, French theologian John Calvin established a rigorous Protestant regime. Even more than Luther, Calvin stressed human weakness and God’s omnipotence. His Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) depicted God as an absolute sovereign. Calvin preached the doctrine of predestination, the idea that God chooses certain people for salvation before they are born and condemns the rest to eternal damnation. In Geneva, he set up a model Christian community and placed spiritual authority in ministers who ruled the city, prohibiting frivolity and luxury. “We know,” wrote Calvin, “that man is of so perverse and crooked a nature, that everyone would scratch out his neighbor’s eyes if there were no bridle to hold them in.” Calvin’s authoritarian doctrine won converts all over Europe, including the Puritans in Scotland and England.

Luther’s criticisms triggered a war between the Holy Roman Empire and the northern principalities in Germany, and soon the controversy between the Roman Catholic Church and radical reformers like Luther and Calvin spread throughout much of Western Europe. The Protestant Reformation, as this movement came to be called, triggered a Counter-Reformation in the Catholic Church that sought change from within and created new monastic and missionary orders, including the Jesuits (founded in 1540), who saw themselves as soldiers of Christ. The competition between these divergent Christian traditions did much to shape European colonization of the Americas. Roman Catholic powers — Spain, Portugal, and France — sought to win souls in the Americas for the Church, while Protestant nations — England and the Netherlands — viewed the Catholic Church as corrupt and exploitative and hoped instead to create godly communities attuned to the true gospel of Christianity.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did the growing influence of the Christian Church affect events in Europe?