America’s History: Printed Page 30

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 27

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 26

Sixteenth-Century Incursions

As Portuguese traders sailed south and east, the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile financed an explorer who looked to the west. As Renaissance rulers, Ferdinand (r. 1474–1516) and Isabella (r. 1474–1504) saw national unity and foreign commerce as the keys to power and prosperity. Married in an arranged match to combine their Christian kingdoms, the young rulers completed the centuries-long reconquista, the campaign by Spanish Catholics to drive Muslim Arabs from the European mainland, by capturing Granada, the last Islamic territory in Western Europe, in 1492. Using Catholicism to build a sense of “Spanishness,” they launched the brutal Inquisition against suspected Christian heretics and expelled or forcibly converted thousands of Jews and Muslims.

Columbus and the Caribbean Simultaneously, Ferdinand and Isabella sought trade and empire by subsidizing the voyages of Christopher Columbus, an ambitious and daring mariner from Genoa. Columbus believed that the Atlantic Ocean, long feared by Arab merchants as a 10,000-mile-wide “green sea of darkness,” was a much narrower channel of water separating Europe from Asia. After cajoling and lobbying for six years, Columbus persuaded Genoese investors in Seville; influential courtiers; and, finally, Ferdinand and Isabella to accept his dubious theories and finance a western voyage to Asia.

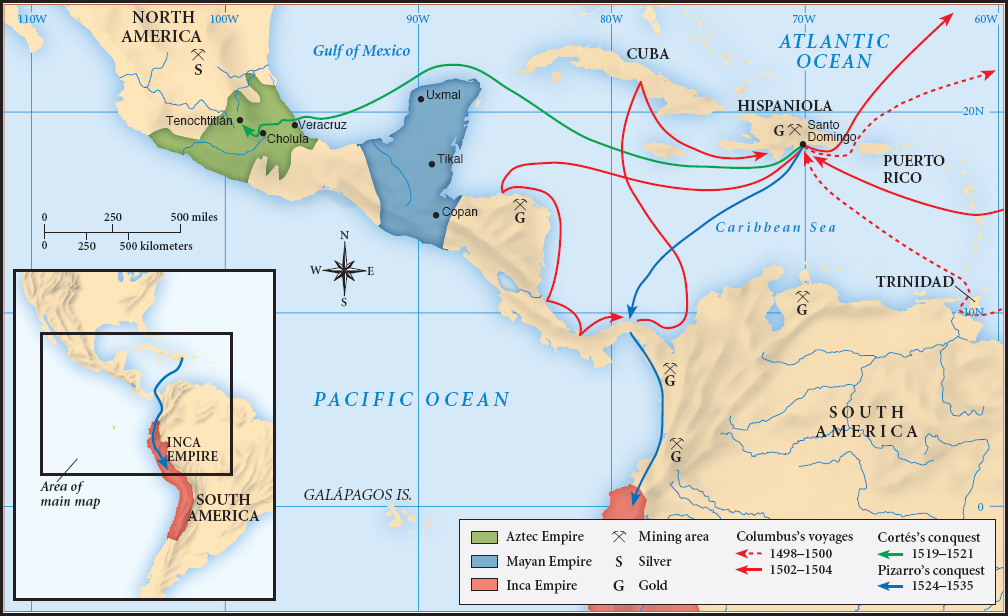

Columbus set sail in three small ships in August 1492. Six weeks later, after a perilous voyage of 3,000 miles, he disembarked on an island in the present-day Bahamas. Believing that he had reached Asia — “the Indies,” in fifteenth-century parlance — Columbus called the native inhabitants Indians and the islands the West Indies. He was surprised by the crude living conditions but expected the native peoples “easily [to] be made Christians.” He claimed the islands for Spain and then explored the neighboring Caribbean islands and demanded tribute from the local Taino, Arawak, and Carib peoples. Buoyed by stories of rivers of gold lying “to the west,” Columbus left forty men on the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and returned triumphantly to Spain (Map 1.5).

|

To see a longer excerpt of Columbus’s views of the West Indies, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

Although Columbus brought back no gold, the Spanish monarchs supported three more of his voyages. Columbus colonized the West Indies with more than 1,000 Spanish settlers — all men — and hundreds of domestic animals. But he failed to find either golden treasures or great kingdoms, and his death in 1506 went virtually unnoticed.

A German geographer soon labeled the newly found continents America in honor of a Florentine explorer, Amerigo Vespucci. Vespucci, who had explored the coast of present-day South America around 1500, denied that the region was part of Asia. He called it a nuevo mundo, a “new world.” The Spanish crown called the two continents Las Indias (“the Indies”) and wanted to make them a new Spanish world.

The Spanish Invasion After brutally subduing the Arawaks and Tainos on Hispaniola, the Spanish probed the mainland for gold and slaves. In 1513, Juan Ponce de León explored the coast of Florida and gave that peninsula its name. In the same year, Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Darien (Panama) and became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean. Rumors of rich Indian kingdoms encouraged other Spaniards, including hardened veterans of the reconquista, to invade the mainland. The Spanish monarchs offered successful conquistadors noble titles, vast estates, and Indian laborers.

With these inducements before him, in 1519 Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) led an army of 600 men to the Yucatán Peninsula. Gathering allies among native peoples who chafed under Aztec rule, he marched on Tenochtitlán and challenged its ruler, Moctezuma. Awed by the Spanish invaders, Moctezuma received Cortés with great ceremony (American Voices). However, Cortés soon took the emperor captive, and following a prolonged siege, he and his men captured the city. The conquest took a devastating toll: the conquerors cut off the city’s supply of food and water, and the residents of Tenochtitlán suffered spectacularly. By 1521, Cortés and his men had toppled the Aztec Empire.

The Spanish had a silent ally: disease. Having been separated from Eurasia for thousands of years, the inhabitants of the Americas had no immunities to common European diseases. After the Spaniards arrived, a massive smallpox epidemic ravaged Tenochtitlán, “striking everywhere in the city,” according to an Aztec source, and killing Moctezuma’s brother and thousands more. “They could not move, they could not stir. … Covered, mantled with pustules, very many people died of them.” Subsequent outbreaks of smallpox, influenza, and measles killed hundreds of thousands of Indians and sapped the survivors’ morale. Exploiting this demographic weakness, Cortés quickly extended Spanish rule over the Aztec Empire. His lieutenants then moved against the Mayan city-states of the Yucatán Peninsula, eventually conquering them as well.

In 1524, Francisco Pizarro set out to accomplish the same feat in Peru. By the time he and his small force of 168 men and 67 horses finally reached their destination in 1532, half of the Inca population had already died from European diseases. Weakened militarily and divided between rival claimants to the throne, the Inca nobility was easy prey. Pizarro killed Atahualpa, the last Inca emperor, and seized his enormous wealth. Although Inca resistance continued for a generation, the conquest was complete by 1535, and Spain was now the master of the wealthiest and most populous regions of the Western Hemisphere.

The Spanish invasion changed life forever in the Americas. Disease and warfare wiped out virtually all of the Indians of Hispaniola — at least 300,000 people. In Peru, the population of 9 million in 1530 plummeted to fewer than 500,000 a century later. Mesoamerica suffered the greatest losses: In one of the great demographic disasters in world history, its population of 20 million Native Americans in 1500 had dwindled to just 3 million in 1650.

Cabral and Brazil At the same time, Portuguese efforts to find a sailing route around the southern tip of Africa led to a surprising find. As Vasco da Gama and his contemporaries experimented with winds and currents, their voyages carried them ever farther away from the African coast and into the Atlantic. On one such voyage in 1500, the Portuguese commander Pedro Alvares Cabral and his fleet were surprised to see land loom up in the west. Cabral named his discovery Ihla da Vera Cruz — the Island of the True Cross — and continued on his way toward India. Others soon followed and changed the region’s name to Brazil after the indigenous tree that yielded a valuable red dye; for several decades, Portuguese sailors traded with the Tupi Indians for brazilwood. Then in the 1530s, to secure Portugal’s claim, King Dom João III sent settlers who began the long, painstaking process of carving out sugar plantations in the coastal lowlands. For several decades, Native Americans supplied most of the labor for these operations, but African slaves gradually replaced them. Brazil would soon become the world’s leading producer of sugar; it would also devour African lives. By introducing the plantation system to the Americas — a form of estate agriculture using slave labor that was pioneered by Italian merchants and crusading knights in the twelfth century and transplanted to the islands off the coast of Africa in the fifteenth century — the Portuguese set in motion one of the most significant developments of the early modern era.

By the end of the sixteenth century, the European colonization of the Americas had barely begun. Yet several of its most important elements were already taking shape. Spanish efforts demonstrated that densely populated empires were especially vulnerable to conquest and were also especially valuable sources of wealth. The Portuguese had discovered the viability of sugar plantations in the tropical regions of the Americas and pioneered the transatlantic slave trade as a way of manning them. And contacts with native peoples revealed their devastating vulnerabilities to Eurasian diseases — one part of the larger phenomenon of the Columbian Exchange (discussed in Chapter 2).