America’s History: Printed Page 645

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 587

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 570

Democrats and the “Solid South”

In the South, the only region where Democrats gained strength in the 1890s, the People’s Party lost ground for distinctive reasons. After the end of Reconstruction, African Americans in most states had continued to vote in significant numbers. As long as Democrats competed for (and sometimes bought) black votes, the possibility remained that other parties could win them away. Populists proposed new measures to help farmers and wage earners — an appealing message for poverty-stricken people of both races. Some white Populists went out of their way to build cross-racial ties. “The accident of color can make no difference in the interest of farmers, croppers, and laborers,” argued Georgia Populist Tom Watson. “You are kept apart that you may be separately fleeced of your earnings.”

Such appeals threatened the foundations of southern politics. Democrats struck back, calling themselves the “white man’s party” and denouncing Populists for advocating “Negro rule.” From Georgia to Texas, many poor white farmers, tenants, and wage earners ignored such appeals and continued to support the Populists in large numbers. Democrats found they could put down the Populist threat only through fraud and violence. Afterward, Pitchfork Ben Tillman of South Carolina openly bragged that he and other southern whites had “done our level best” to block “every last” black vote. “We stuffed ballot boxes,” he said in 1900. “We shot them. We are not ashamed of it.” “We had to do it,” a Georgia Democrat later argued. “Those damned Populists would have ruined the country.”

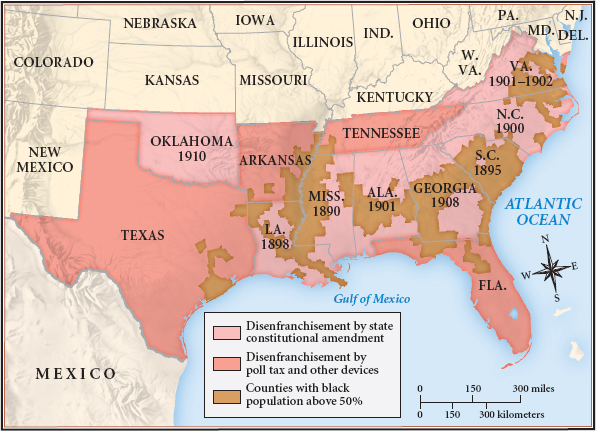

Having suppressed the political revolt, Democrats looked for new ways to enforce white supremacy. In 1890, a constitutional convention in Mississippi had adopted a key innovation: an “understanding clause” that required would-be voters to interpret parts of the state constitution, with local Democratic officials deciding who met the standard. After the Populist uprising, such measures spread to other southern states. Louisiana’s grandfather clause, which denied the ballot to any man whose grandfather had been unable to vote in slavery days, was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court. But in Williams v. Mississippi (1898), the Court allowed poll taxes and literacy tests to stand. By 1908, every southern state had adopted such measures.

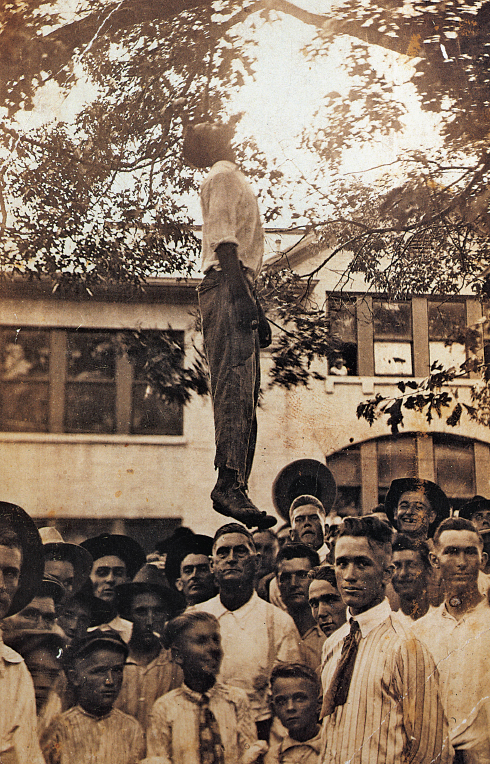

The impact of disenfranchisement can hardly be overstated (Map 20.3). Across the South, voter turnout plunged, from above 70 percent to 34 percent or even lower. Not only blacks but also many poor whites ceased to vote. Since Democrats faced virtually no opposition, action shifted to the “white primaries,” where Democratic candidates competed for nominations. Some former Populists joined the Democrats in openly advocating white supremacy. The racial climate hardened. Segregation laws proliferated. Lynchings of African Americans increasingly occurred in broad daylight, with crowds of thousands gathered to watch.

The convict lease system, which had begun to take hold during Reconstruction, also expanded. Blacks received harsh sentences for crimes such as “vagrancy,” often when they were traveling to find work or if they could not produce a current employment contract. By the 1890s, Alabama depended on convict leasing for 6 percent of its total revenue. Prisoners were overwhelmingly black: a 1908 report showed that almost 90 percent of Georgia’s leased convicts were black; out of a white population of 1.4 million, only 322 were in prison. Calling attention to the torture and deaths of prisoners, as well as the damaging economic effect of their unpaid labor, reformers, labor unions, and Populists protested the situation strenuously. But “reforms” simply replaced convict leasing with the chain gang, in which prisoners worked directly for the state on roadbuilding and other projects, under equally cruel conditions. All these developments depended on a political Solid South in which Democrats exercised almost complete control.

The impact of the 1890s counterrevolution was dramatically illustrated in Grimes County, a cotton-growing area in east Texas where blacks comprised more than half of the population. African American voters kept the local Republican Party going after Reconstruction and regularly sent black representatives to the Texas legislature. Many local white Populists dismissed Democrats’ taunts of “negro supremacy,” and a Populist-Republican coalition swept the county elections in 1896 and 1898. But after their 1898 defeat, Democrats in Grimes County organized a secret brotherhood and forcibly prevented blacks from voting in town elections, shooting two in cold blood. The Populist sheriff proved unable to bring the murderers to justice. Reconstituted in 1900 as the White Man’s Party, Democrats carried Grimes County by an overwhelming margin. Gunmen then laid siege to the Populist sheriff’s office, killed his brother and a friend, and drove the wounded sheriff out of the county. The White Man’s Party ruled Grimes County for the next fifty years.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did politics change in the South between the 1880s and the 1910s?