America’s History: Printed Page 646

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 590

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 573

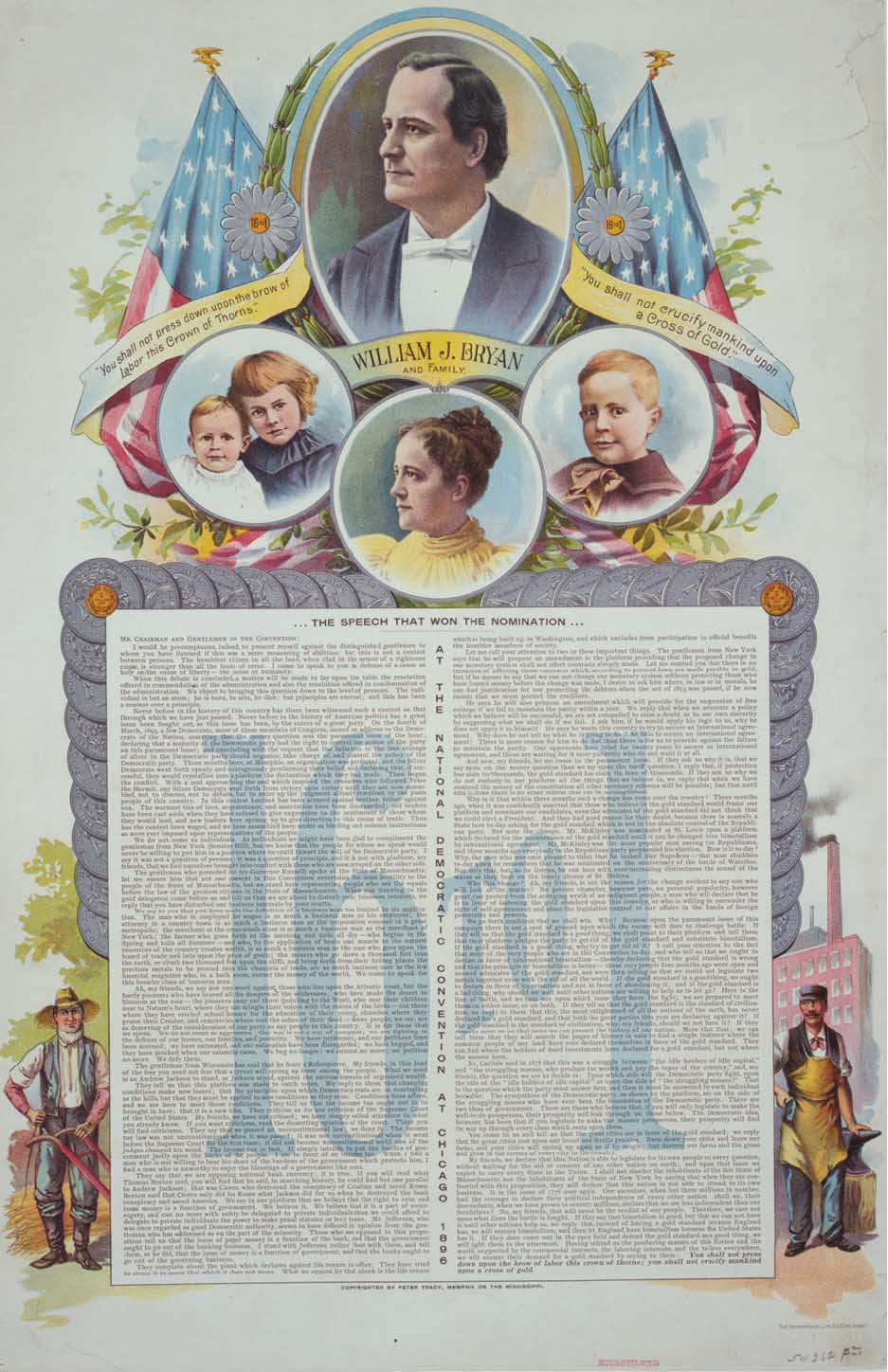

New National Realities

While their southern racial policies were abhorrent, the national Democrats simultaneously amazed the country in 1896 by embracing parts of the Populists’ radical farmer-labor program. They nominated for president a young Nebraska congressman, free-silver advocate William Jennings Bryan, who passionately defended farmers and attacked the gold standard. “Burn down your cities and leave our farms,” Bryan declared in his famous convention speech, “and your cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.” He ended with a vow: “You shall not crucify mankind on a cross of gold.” Cheering delegates endorsed a platform calling for free silver and a federal income tax on the wealthy that would replace tariffs as a source of revenue. Democrats, long defenders of limited government, were moving toward a more activist stance.

Populists, reeling from recent defeats, endorsed Bryan in the campaign, but their power was waning. Populist leader Tom Watson, who wanted a separate program, more radical than Bryan’s, observed that Democrats in 1896 had cast the Populists as “Jonah while they play whale.” The People’s Party never recovered from its electoral losses in 1894 and from Democrats’ ruthless opposition in the South. By 1900, rural voters pursued reform elsewhere, particularly through the new Bryan wing of the Democratic Party.

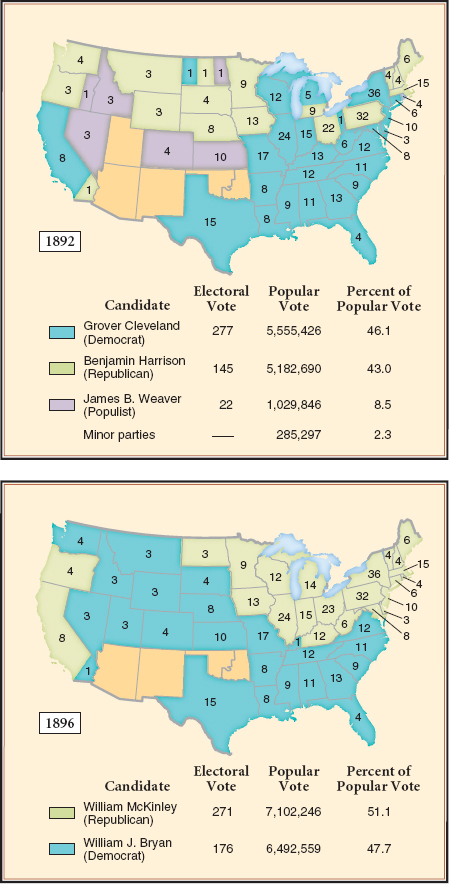

Meanwhile, horrified Republicans denounced Bryan’s platform as anarchistic. Their nominee, the Ohio congressman and tariff advocate William McKinley, chose a brilliant campaign manager, Ohio coal and shipping magnate Marcus Hanna, who orchestrated an unprecedented corporate fund-raising campaign. Under his guidance, the party backed away from moral issues such as prohibition of liquor and reached out to new immigrants. Though the popular vote was closer, McKinley won big: 271 electoral votes to Bryan’s 176 (Map 20.4).

Nationwide, as in the South, the realignment of the 1890s prompted new measures to exclude voters. Influenced by classical liberals’ denunciations of “unfit voters,” many northern states imposed literacy tests and restrictions on immigrant voting. Leaders of both major parties, determined to prevent future Populist-style threats, made it more difficult for new parties to get candidates listed on the ballot. In the wake of such laws, voter turnout declined, and the electorate narrowed in ways that favored the native-born and wealthy.

Antidemocratic restrictions on voting helped, paradoxically, to foster certain democratic innovations. Having excluded or reduced the number of poor, African American, and immigrant voters, elite and middle-class reformers felt more comfortable increasing the power of the voters who remained. Both major parties increasingly turned to the direct primary, asking voters (in most states, registered party members) rather than party leaders to choose nominees. Another measure that enhanced democratic participation was the Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution (1913), requiring that U.S. senators be chosen not by state legislatures, but by popular vote. Though many states had adopted the practice well before 1913, southern states had resisted, since Democrats feared that it might give more power to their political opponents. After disenfranchisement, such objections faded and the measure passed. Thus disenfranchisement enhanced the power of remaining voters in multiple, complicated ways.

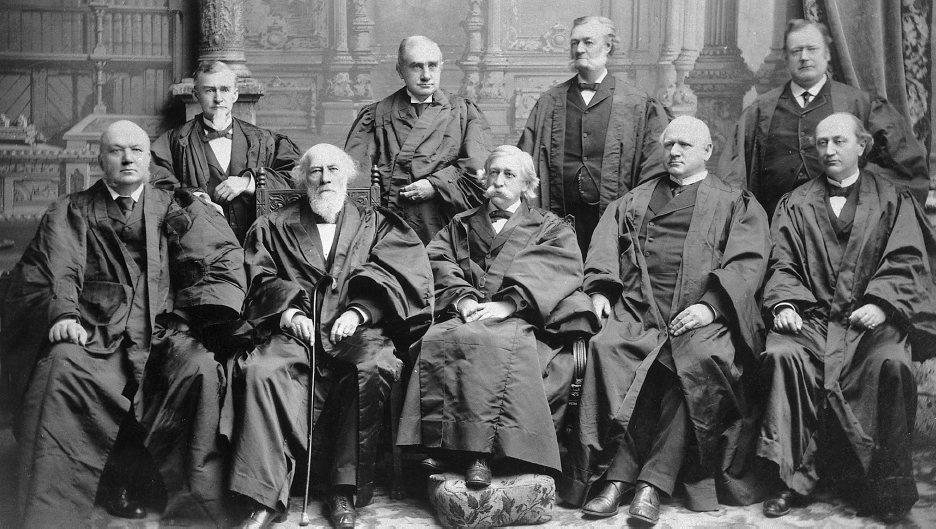

At the same time, the Supreme Court proved hostile to many proposed reforms. In 1895, for example, it struck down a recently adopted federal income tax on the wealthy. The Court ruled that unless this tax was calculated on a per-state basis, rather than by the wealth of individuals, it could not be levied without a constitutional amendment. It took progressives nineteen years to achieve that goal.

Labor organizations also suffered in the new political regime, as federal courts invalidated many regulatory laws passed to protect workers. As early as 1882, in the case of In re Jacobs, the New York State Court of Appeals struck down a public-health law that prohibited cigar manufacturing in tenements, arguing that such regulation exceeded the state’s police powers. In Lochner v. New York (1905), the U.S. Supreme Court told New York State it could not limit bakers’ workday to ten hours because that violated bakers’ rights to make contracts. Judges found support for such rulings in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibited states from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Though the clause had been intended to protect former slaves, courts used it to shield contract rights, with judges arguing that they were protecting workers’ freedom from government regulation. Interpreted in this way, the Fourteenth Amendment was a major obstacle to regulation of private business.

Farmer and labor advocates, along with urban progressives who called for more government regulation, disagreed with such rulings. They believed judges, not state legislators, were overreaching. While courts treated employers and employees as equal parties, critics dismissed this as a legal fiction. “Modern industry has reduced ‘freedom of contract’ to a paper privilege,” declared one labor advocate, “a mere figure of rhetoric.” Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., dissenting in the Lochner decision, agreed. If the choice was between working and starving, he observed, how could bakers “choose” their hours of work? Holmes’s view, known as legal realism, eventually won judicial favor, but only after years of progressive and labor activism.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

What developments caused the percentage of Americans who voted to plunge after 1900, and what role did courts play in antidemocratic developments?