America’s History: Printed Page 652

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 596

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 578

Diverse Progressive Goals

The revolt of Republican Insurgents signaled the strength of grassroots demands for change. No one described these emerging goals more eloquently than Jane Addams, who famously declared in Democracy and Social Ethics (1902), “The cure for the ills of Democracy is more Democracy.” It was a poignant statement, given the sharply antidemocratic direction American politics had taken since the 1890s. What, now, should more democracy look like? Various groups of progressives — women, antipoverty reformers, African American advocates — often disagreed about priorities and goals. Some, frustrated by events in the United States, traveled abroad to study inspiring experiments in other nations, hoping to bring ideas home (America Compared).

States also served as seedbeds of change. Theodore Roosevelt dubbed Wisconsin a “laboratory of democracy” under energetic Republican governor Robert La Follette (1901–1905). La Follette promoted what he called the Wisconsin Idea — greater government intervention in the economy, with reliance on experts, particularly progressive economists, for policy recommendations. Like Addams, La Follette combined respect for expertise with commitment to “more Democracy.” He won battles to restrict lobbying and to give Wisconsin citizens the right of recall — voting to remove unpopular politicians from office — and referendum — voting directly on a proposed law, rather than leaving it in the hands of legislators. Continuing his career in the U.S. Senate, La Follette, like Roosevelt, advocated increasingly aggressive measures to protect workers and rein in corporate power.

Protecting the Poor The urban settlement movement called attention to poverty in America’s industrial cities. In the emerging social sciences, experts argued that unemployment and crowded slums were not caused by laziness and ignorance, as elite Americans had long believed. Instead, as journalist Robert Hunter wrote in his landmark study, Poverty (1904), such problems resulted from “miserable and unjust social conditions.” Charity work was at best a limited solution. “How vain to waste our energies on single cases of relief,” declared one reformer, “when society should aim at removing the prolific sources of all the woe.”

By the early twentieth century, reformers placed particular emphasis on labor conditions for women and children. The National Child Labor Committee, created in 1907, hired photographer Lewis Hine to record brutal conditions in mines and mills where children worked. (See Hine’s photograph.) Impressed by the committee’s investigations, Theodore Roosevelt sponsored the first White House Conference on Dependent Children in 1909, bringing national attention to child welfare issues. In 1912, momentum from the conference resulted in creation of the Children’s Bureau in the U.S. Labor Department.

Those seeking to protect working-class women scored a major triumph in 1908 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Muller v. Oregon, which upheld an Oregon law limiting women’s workday to ten hours. Given the Court’s ruling three years earlier in Lochner v. New York, it was a stunning victory. To win the case, the National Consumers’ League (NCL) recruited Louis Brandeis, a son of Jewish immigrants who was widely known as “the people’s lawyer” for his eagerness to take on vested interests. Brandeis’s legal brief in the Muller case devoted only two pages to the constitutional issue of state police powers. Instead, Brandeis rested his arguments on data gathered by the NCL describing the toll that long work hours took on women’s health. The “Brandeis brief” cleared the way for use of social science research in court decisions. Sanctioning a more expansive role for state governments, the Muller decision encouraged women’s organizations to lobby for further reforms. Their achievements included the first law providing public assistance for single mothers with dependent children (Illinois, 1911) and the first minimum wage law for women (Massachusetts, 1912).

Muller had drawbacks, however. Though men as well as women suffered from long work hours, the Muller case did not protect men. Brandeis’s brief treated all women as potential mothers, focusing on the state’s interest in protecting future children. Brandeis and his allies hoped this would open the door to broader regulation of working hours. The Supreme Court, however, seized on motherhood as the key issue, asserting that the female worker, because of her maternal function, was “in a class by herself, and legislation for her protection may be sustained, even when like legislation is not necessary for men.” This conclusion dismayed labor advocates and divided female reformers for decades afterward.

Male workers did benefit, however, from new workmen’s compensation measures. Between 1910 and 1917, all the industrial states enacted insurance laws covering on-the-job accidents, so workers’ families would not starve if a breadwinner was injured or killed. Some states also experimented with so-called mothers’ pensions, providing state assistance after a breadwinner’s desertion or death. Mothers, however, were subjected to home visits to determine whether they “deserved” government aid; injured workmen were not judged on this basis, a pattern of gender discrimination that reflected the broader impulse to protect women, while also treating them differently from men. Mothers’ pensions reached relatively small numbers of women, but they laid foundations for the national program Aid to Families with Dependent Children, an important component of the Social Security Act of 1935.

While federalism gave the states considerable freedom to innovate, it hampered national reforms. In some states, for example, opponents of child labor won laws barring young children from factory work and strictly regulating hours and conditions for older children’s labor. In the South, however, and in coal-mining states like Pennsylvania, companies fiercely resisted such laws — as did many working-class parents who relied on children’s income to keep the family fed. A proposed U.S. constitutional amendment to abolish child labor never won ratification; only four states passed it. Tens of thousands of children continued to work in low-wage jobs, especially in the South. The same decentralized power that permitted innovation in Wisconsin hampered the creation of national minimum standards for pay and job safety.

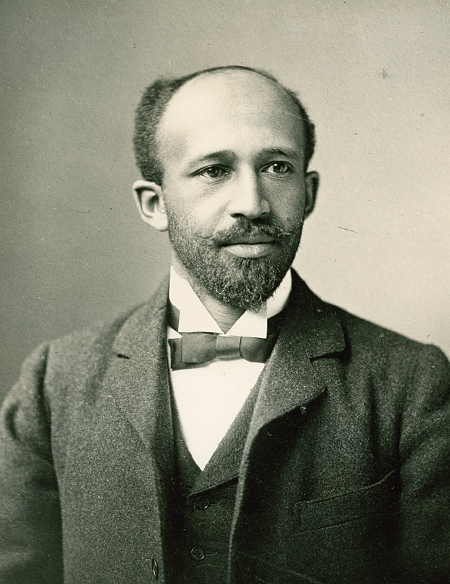

The Birth of Modern Civil Rights Reeling from disenfranchisement and the sanction of racial segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), African American leaders faced distinctive challenges. Given the obvious deterioration of African American rights, a new generation of black leaders proposed bolder approaches than those popularized earlier by Booker T. Washington. Harvard-educated sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois called for a talented tenth of educated blacks to develop new strategies. “The policy of compromise has failed,” declared William Monroe Trotter, pugnacious editor of the Boston Guardian. “The policy of resistance and aggression deserves a trial.”

In 1905, Du Bois and Trotter called a meeting at Niagara Falls — on the Canadian side, because no hotel on the U.S. side would admit blacks. The resulting Niagara Principles called for full voting rights; an end to segregation; equal treatment in the justice system; and equal opportunity in education, jobs, health care, and military service. These principles, based on African American pride and an uncompromising demand for full equality, guided the civil rights movement throughout the twentieth century.

In 1908, a bloody race riot broke out in Springfield, Illinois. Appalled by the white mob’s violence in the hometown of Abraham Lincoln, New York settlement worker Mary White Ovington called together a group of sympathetic progressives to formulate a response. Their meeting led in 1909 to creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Most leaders of the Niagara Movement soon joined; W. E. B. Du Bois became editor of the NAACP journal, The Crisis. The fledgling group found allies in many African American women’s clubs and churches. It also cooperated with the National Urban League (1911), a union of agencies that assisted black migrants in the North. Over the coming decades, these groups grew into a powerful force for racial justice.

The Problem of Labor Leaders of the nation’s dominant union, the American Federation of Labor, were slow to ally with progressives. They had long believed workers should improve their situation through strikes and direct negotiation with employers, not through politics. But by the 1910s, as progressive reformers came forward with solutions, labor leaders in state after state began to join the cause.

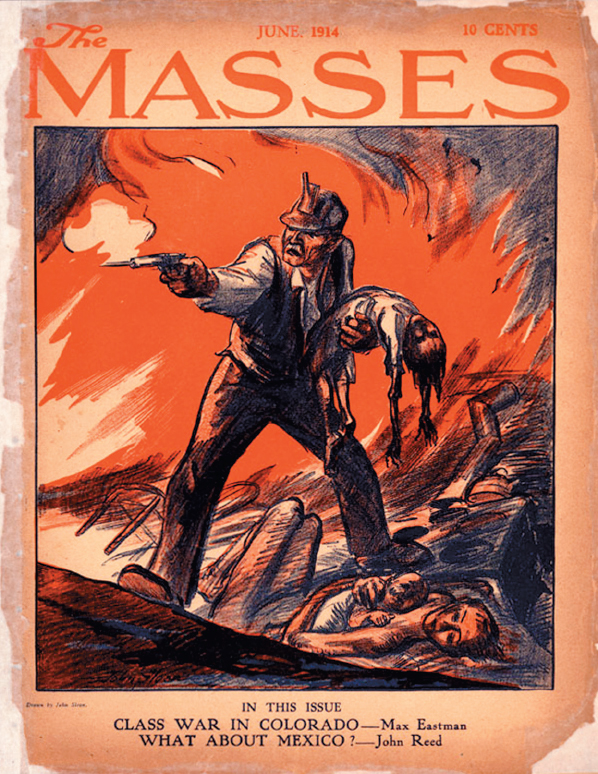

The nation also confronted a daring wave of radical labor militancy. In 1905, the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), led by fiery leaders such as William “Big Bill” Haywood, helped create a new movement, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The Wobblies, as they were called, fervently supported the Marxist class struggle. As syndicalists, they believed that by resisting in the workplace and ultimately launching a general strike, workers could overthrow capitalism. A new society would emerge, run directly by workers. At its height, around 1916, the IWW had about 100,000 members. Though divided by internal conflicts, the group helped spark a number of local protests during the 1910s, including strikes of rail car builders in Pennsylvania, textile operatives in Massachusetts, rubber workers in Ohio, and miners in Minnesota.

Meanwhile, after midnight on October 1, 1910, an explosion ripped through the Los Angeles Times headquarters, killing twenty employees and wrecking the building. It turned out that John J. McNamara, a high official of the American Federation of Labor’s Bridge and Structural Iron Workers Union, had planned the bombing against the fiercely antiunion Times. McNamara’s brother and another union member had carried out the attack. The bombing created a sensation, as did the terrible Triangle Shirtwaist fire and the IWW’s high-profile strikes. What should be done? As the election of 1912 approached, labor issues moved high on the nation’s agenda.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did various grassroots reformers define “progressivism,” and how did their views differ from Theodore Roosevelt’s version of “progressivism”?