America’s History: Printed Page 656

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 601

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 582

The Election of 1912

Retirement did not sit comfortably with Theodore Roosevelt. Returning from a yearlong safari in Africa in 1910 and finding Taft wrangling with the Insurgents, Roosevelt itched to jump in. In a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, in August 1910, he called for a New Nationalism. In modern America, he argued, private property had to be controlled “to whatever degree the public welfare may require it.” He proposed a federal child labor law, more recognition of labor rights, and a national minimum wage for women. Pressed by friends like Jane Addams, Roosevelt also endorsed women’s suffrage. Most radical was his attack on the legal system. Insisting that courts blocked reform, Roosevelt proposed sharp curbs on their powers (American Voices).

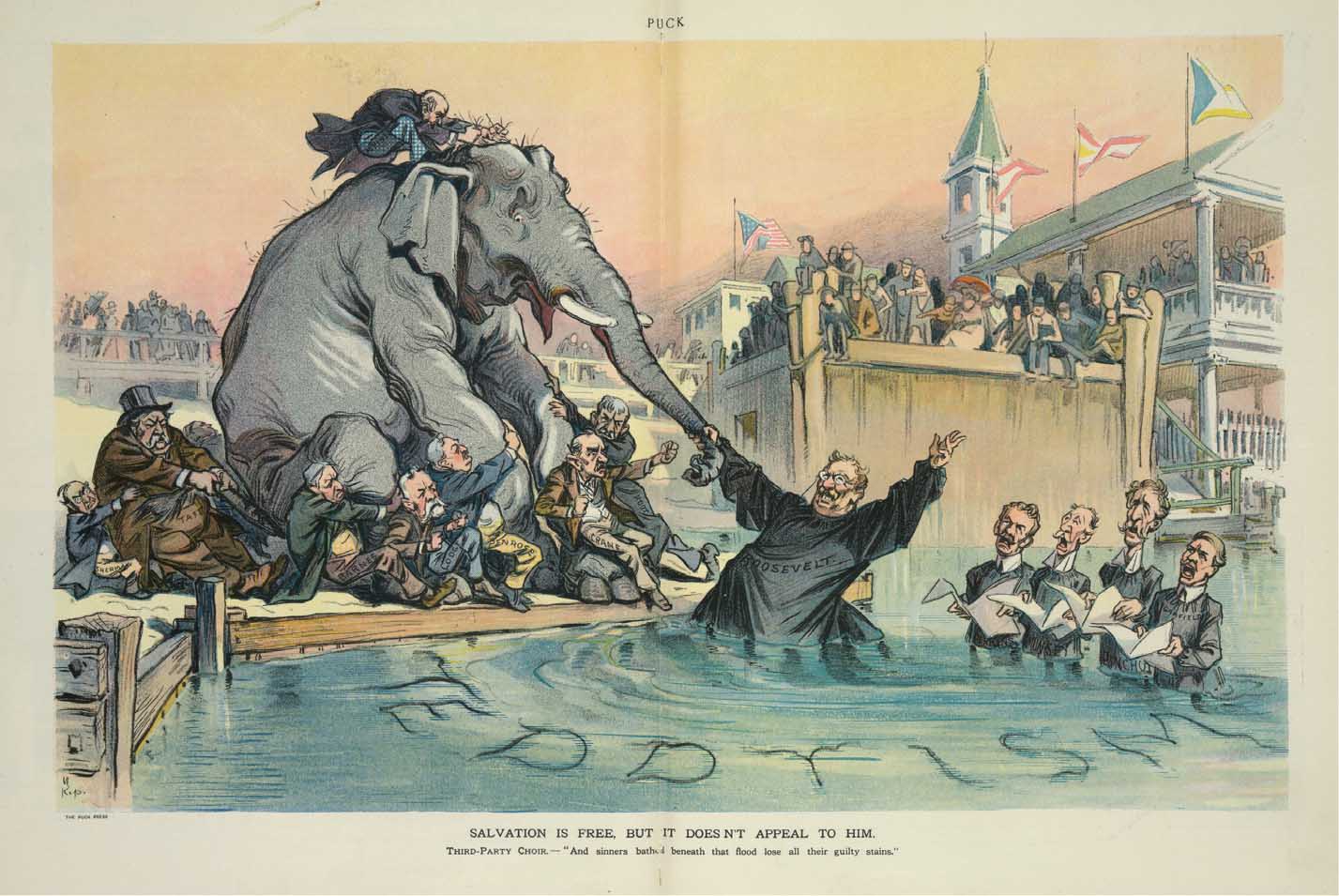

Early in 1912, Roosevelt announced himself as a Republican candidate for president. A battle within the party ensued. Roosevelt won most states that held primary elections, but Taft controlled party caucuses elsewhere. Dominated by regulars, the Republican convention chose Taft. Roosevelt then led his followers into what became known as the Progressive Party, offering his New Nationalism directly to the people. Though Jane Addams harbored private doubts (especially about Roosevelt’s mania for battleships), she seconded his nomination, calling the Progressive Party “the American exponent of a world-wide movement for juster social conditions.” In a nod to Roosevelt’s combative stance, party followers called themselves “Bull Mooses.”

Roosevelt was not the only rebel on the ballot: the major parties also faced a challenge from charismatic socialist Eugene V. Debs. In the 1890s, Debs had founded the American Railway Union (ARU), a broad-based group that included both skilled and unskilled workers. In 1894, amid the upheavals of depression and popular protest, the ARU had boycotted luxury Pullman sleeping cars, in support of a strike by workers at the Pullman Company. Railroad managers, claiming the strike obstructed the U.S. mail, persuaded Grover Cleveland’s administration to intervene against the union. The strike failed, and Debs served time in prison along with other ARU leaders. The experience radicalized him, and in 1901 he launched the Socialist Party of America. Debs translated socialism into an American idiom, emphasizing the democratic process as a means to defeat capitalism. By the early 1910s, his party had secured a minor but persistent role in politics. Both the Progressive and Socialist parties drew strength from the West, a region with vigorous urban reform movements and a legacy of farmer-labor activism.

Watching the rise of the Progressives and Socialists, Democrats were keen to build on dramatic gains they had made in the 1910 midterm election. Among their younger leaders was Virginia-born Woodrow Wilson, who as New Jersey’s governor had compiled an impressive reform record, including passage of a direct primary, workers’ compensation, and utility regulation. In 1912, he won the Democrats’ nomination. Wilson possessed, to a fault, the moral certainty that characterized many elite progressives. He had much in common with Roosevelt. “The old time of individual competition is probably gone by,” he admitted, agreeing for more federal measures to restrict big business. But his goals were less sweeping than Roosevelt’s, and only gradually did he hammer out a reform program, calling it the New Freedom. “If America is not to have free enterprise,” Wilson warned, “then she can have freedom of no sort whatever.” He claimed Roosevelt’s program represented collectivism, whereas the New Freedom would preserve political and economic liberty.

With four candidates in the field — Taft, Roosevelt, Wilson, and Debs — the 1912 campaign generated intense excitement. Democrats continued to have an enormous blind spot: their opposition to African American rights. But Republicans, despite plentiful opportunities, had also conspicuously failed to end segregation or pass antilynching laws. Though African American leaders had high hopes for the Progressive Party, they were crushed when the new party refused to seat southern black delegates or take a stand for racial equality. W. E. B. Du Bois considered voting for Debs, calling the Socialists the only party “which openly recognized Negro manhood.” But he ultimately endorsed Wilson. Across the North, in a startling shift, thousands of African American men and women worked and voted for Wilson, hoping Democrats’ reform energy would benefit Americans across racial lines. The change helped lay the foundations for Democrats’ New Deal coalition of the 1930s.

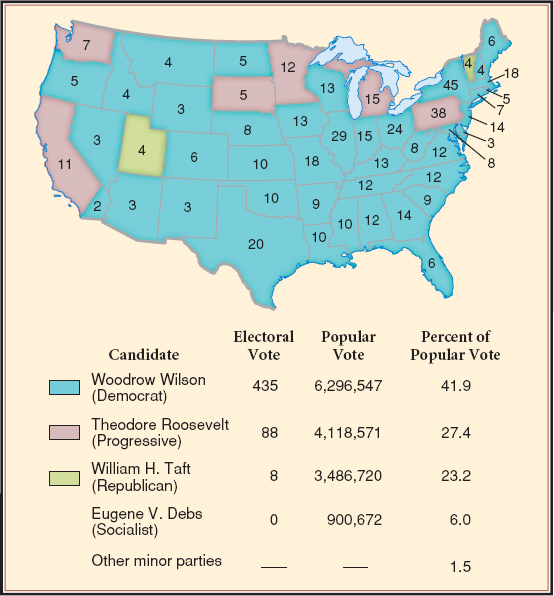

Despite the intense campaign, Republicans’ division between Taft and Roosevelt made the result fairly easy to predict. Wilson won, though he received only 42 percent of the popular vote and almost certainly would have lost if Roosevelt had not been in the race (Map 20.5). In comparison with Roosevelt and Debs, Wilson appeared to be a rather old-fashioned choice. But with labor protests cresting and progressives gaining support, Wilson faced intense pressure to act.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

Why did the election of 1912 feature four candidates, and how did their platforms differ?