America’s History: Printed Page 638

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 580

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 563

Electoral Politics After Reconstruction

The end of Reconstruction ushered in a period of fierce partisan conflict. Republicans and Democrats traded control of the Senate three times between 1880 and 1894, and the House majority five times. Causes of this tight competition included northerners’ disillusionment with Republican policies and the resurgence of southern Democrats, who regained a strong base in Congress. Dizzying population growth also changed the size and shape of the House of Representatives. In 1875, it counted 243 seats; two decades later, that had risen to 356. Between 1889 and 1896, entry of seven new western states — Montana, North and South Dakota, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah — contributed to political instability.

Heated competition and the legacies of the Civil War drew Americans into politics. Union veterans donned their uniforms to march in Republican parades, while ex-Confederate Democrats did the same in the South. When politicians appealed to war loyalties, critics ridiculed them for “waving the bloody shirt”: whipping up old animosities that ought to be set aside. For those who had fought or lost beloved family members in the conflict, however — as well as those struggling over African American rights in the South — war issues remained crucial. Many voters also had strong views on economic policies, especially Republicans’ high protective tariffs. Proportionately more voters turned out in presidential elections from 1876 to 1892 than at any other time in American history.

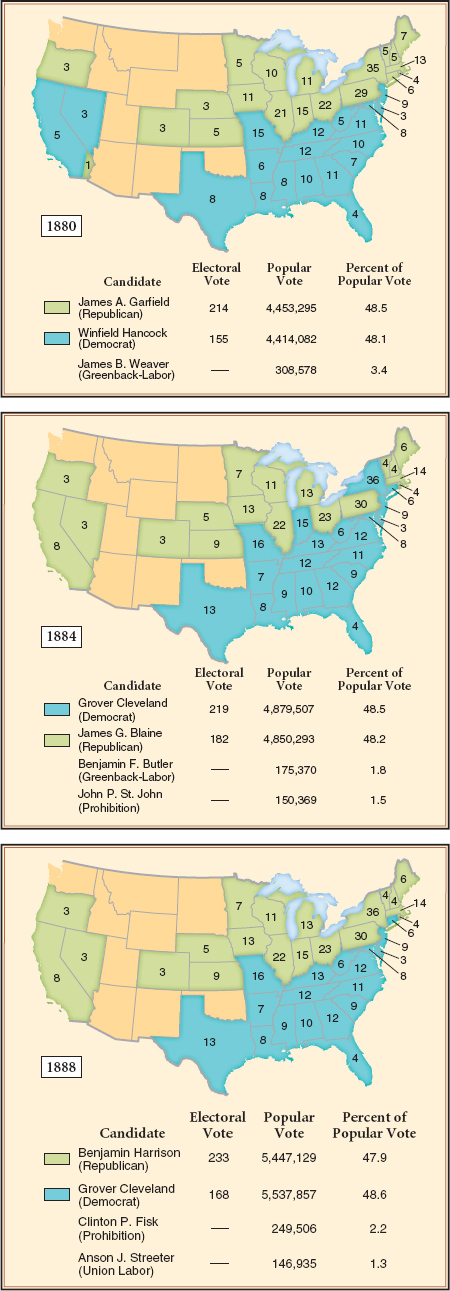

The presidents of this era had limited room to maneuver in a period of narrow victories, when the opposing party often held one or both houses of Congress. Republicans Rutherford B. Hayes and Benjamin Harrison both won the electoral college but lost the popular vote. In 1884, Democrat Grover Cleveland won only 29,214 more votes than his opponent, James Blaine, while almost half a million voters rejected both major candidates (Map 20.1). With key states decided by razor-thin margins, both Republicans and Democrats engaged in vote buying and other forms of fraud. The fierce struggle for advantage also prompted innovations in political campaigning (Thinking Like a Historian).

Some historians have characterized this period as a Gilded Age, when politics was corrupt and stagnant and elections centered on “meaningless hoopla.” The term Gilded Age, borrowed from the title of an 1873 novel cowritten by Mark Twain, suggested that America had achieved a glittery outer coating of prosperity and lofty rhetoric, but underneath suffered from moral decay. Economically, the term Gilded Age seems apt: as we have seen in previous chapters, a handful of men made spectacular fortunes, and their “Gilded” triumphs belied a rising crisis of poverty, pollution, and erosion of workers’ rights. But political leaders were not blind to these problems, and the political scene was hardly idle or indifferent. Rather, Americans bitterly disagreed about what to do. Nonetheless, as early as the 1880s, Congress passed important new federal measures to clean up corruption and rein in corporate power. That decade deserves to be considered an early stage in the emerging Progressive Era.

New Initiatives One of the first reforms resulted from tragedy. On July 2, 1881, only four months after entering the White House, James Garfield was shot at a train station in Washington, D.C. (“Assassination,” he had told a friend, “can no more be guarded against than death by lightning, and it is best not to worry about either.”) After lingering for several agonizing months, Garfield died. Most historians now believe the assassin, Charles Guiteau, suffered from mental illness. But reformers then blamed the spoils system, arguing that Guiteau had murdered Garfield out of disappointment in the scramble for patronage, the granting of government jobs to party loyalists.

In the wake of Garfield’s death, Congress passed the Pendleton Act (1883), establishing a nonpartisan Civil Service Commission to fill federal jobs by examination. Initially, civil service applied to only 10 percent of such jobs, but the act laid the groundwork for a sweeping transformation of public employment. By the 1910s, Congress extended the act to cover most federal positions; cities and states across the country enacted similar laws.

Civil service laws had their downside. In the race for government jobs, they tilted the balance toward middle-class applicants who could perform well on tests. “Firemen now must know equations,” complained a critic, “and be up on Euclid too.” But the laws put talented professionals in office and discouraged politicians from appointing unqualified party hacks. The civil service also brought stability and consistency to government, since officials did not lose their jobs every time their party lost power. In the long run, civil service laws markedly reduced corruption.

Leaders of the civil service movement included many classical liberals: former Republicans who became disillusioned with Reconstruction and advocated smaller, more professionalized government. Many had opposed President Ulysses S. Grant’s reelection in 1872. In 1884, they again left the Republican Party because they could not stomach its scandal-tainted candidate, James Blaine. Liberal Republicans — ridiculed by their enemies as Mugwumps (fence-sitters who had their “mugs” on one side and their “wumps” on the other) — helped elect Democrat Grover Cleveland. They believed he shared their vision of smaller government.

As president, Cleveland showed that he largely did share their views. He vetoed, for example, thousands of bills providing pensions for individual Union veterans. But in 1887, responding to pressure from farmer-labor advocates in the Democratic Party who demanded action to limit corporate power, he signed the Interstate Commerce Act. At the same time, municipal and state-level initiatives were showing how expanded government could help solve industrial problems. In the 1870s and early 1880s, many states created Bureaus of Labor Statistics to investigate workplace safety and unemployment. Some appointed commissions to oversee key industries, from banking to dairy farming. By later standards, such commissions were underfunded, but even when they lacked legal power, energetic commissioners could serve as public advocates, exposing unsafe practices and generating pressure for further laws.

Republican Activism In 1888, after a decade of divided government, Republicans gained control of both Congress and the White House. They pursued an ambitious agenda they believed would meet the needs of a modernizing nation. In 1890, Congress extended pensions to all Union veterans and yielded to growing public outrage over trusts by passing a law to regulate interstate corporations. Though it proved difficult to enforce and was soon weakened by the Supreme Court, the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) was the first federal attempt to forbid any “combination, in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade.”

President Benjamin Harrison also sought to protect black voting rights in the South. Warned during his campaign that the issue was politically risky, Harrison vowed that he would not “purchase the presidency by a compact of silence upon this question.” He found allies in Congress. Massachusetts representative Henry Cabot Lodge drafted the Federal Elections Bill of 1890, or Lodge Bill, proposing that whenever one hundred citizens in any district appealed for intervention, a bipartisan federal board could investigate and seat the rightful winner.

Despite cries of outrage from southern Democrats, who warned that it meant “Negro supremacy,” the House passed the measure. But it met resistance in the Senate. Northern classical liberals, who wanted the “best men” to govern through professional expertise, thought it provided too much democracy, while machine bosses feared the threat of federal interference in the cities. Unexpectedly, many western Republicans also opposed the bill — and with the entry of ten new states since 1863, the West had gained enormous clout. Senator William Stewart of Nevada, who had southern family ties, claimed that federal oversight of elections would bring “monarchy or revolution.” He and his allies killed the bill by a single vote.

The defeat was a devastating blow to those seeking to defend black voting rights. In the verdict of one furious Republican leader who supported Lodge’s proposal, the episode marked the demise of the party of emancipation. “Think of it,” he fumed. “Nevada, barely a respectable county, furnished two senators to betray the Republican Party and the rights of citizenship.”

Other Republican initiatives also proved unpopular — at the polls as well as in Congress. In the Midwest, swing voters reacted against local Republican campaigns to prohibit liquor sales and end state funding for Catholic schools. Blaming high consumer prices on protective tariffs, other voters rejected Republican economic policies. In a major shift in the 1890 election, Democrats captured the House of Representatives. Two years later, by the largest margin in twenty years, voters reelected Democrat Grover Cleveland to the presidency for a nonconsecutive second term. Republican congressmen abandoned any further attempt to enforce fair elections in the South.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What factors led to close party competition in the 1880s?