America’s History: Printed Page 678

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 620

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 601

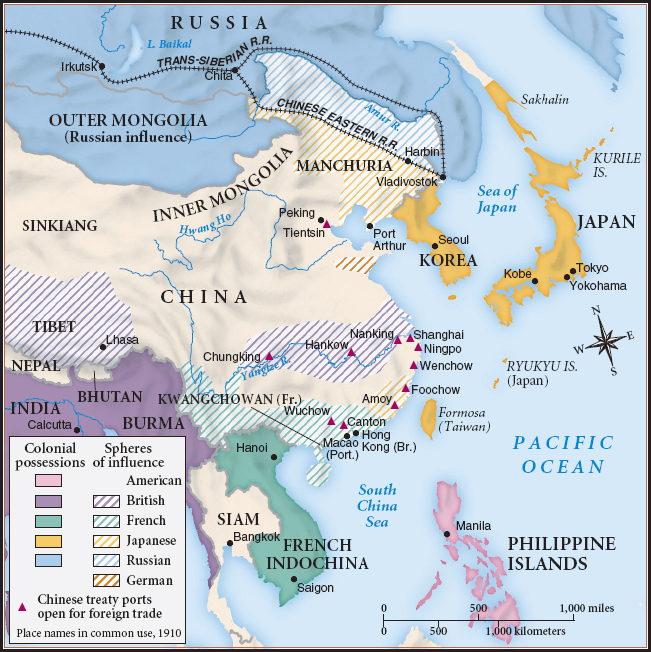

The Open Door in Asia

U.S. officials and business leaders had a burning interest in East Asian markets, but they were entering a crowded field (Map 21.1). In the late 1890s, following Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, Japan, Russia, Germany, France, and Britain divided coastal China into spheres of influence. Fearful of being shut out, U.S. Secretary of State John Hay sent these powers a note in 1899, claiming the right of equal trade access — an “open door” — for all nations seeking to do business in China. The United States lacked leverage in Asia, and Hay’s note elicited only noncommittal responses. But he chose to interpret this as acceptance of his position.

When a secret society of Chinese nationalists, known outside China as “Boxers” because of their pugnacious political stance, rebelled against foreign occupation in 1900, the United States sent 5,000 troops to join a multinational campaign to break the nationalists’ siege of European offices in Beijing. Hay took this opportunity to assert a second open door principle: China must be preserved as a “territorial and administrative entity.” As long as the legal fiction of an independent China survived, Americans could claim equal access to its market.

European and American plans were, however, unsettled by Japan’s emergence as East Asia’s dominant power. A decade after its victory over China, Japan responded to Russian bids for control of both Korea and Manchuria, in northern China, by attacking the tzar’s fleet at Russia’s leased Chinese port. In a series of brilliant victories, the Japanese smashed the Russian forces. Westerners were shocked: for the first time, a European power had been defeated by a non-Western nation. Conveying both admiration and alarm, American cartoonists sketched Japan as a martial artist knocking down the Russian giant. Roosevelt mediated a settlement to the war in 1905, receiving for his efforts the first Nobel Peace Prize awarded to an American.

Though he was contemptuous of other Asians, Roosevelt respected the Japanese, whom he called “a wonderful and civilized people.” More important, he understood Japan’s rising military might and aligned himself with the mighty. The United States approved Japan’s “protectorate” over Korea in 1905 and, six years later, its seizure of full control. With Japan asserting harsh authority over Manchuria, energetic Chinese diplomat Yüan Shih-k’ai tried to encourage the United States to intervene. But Roosevelt reviewed America’s weak position in the Pacific and declined. He conceded that Japan had “a paramount interest in what surrounds the Yellow Sea.” In 1908, the United States and Japan signed the Root-Takahira Agreement, confirming principles of free oceanic commerce and recognizing Japan’s authority over Manchuria.

William Howard Taft entered the White House in 1909 convinced that the United States had been shortchanged in Asia. He pressed for a larger role for American investors, especially in Chinese railroad construction. Eager to promote U.S. business interests abroad, he hoped that infusions of American capital would offset Japanese power. When the Chinese Revolution of 1911 toppled the Manchu dynasty, Taft supported the victorious Nationalists, who wanted to modernize their country and liberate it from Japanese domination. The United States had entangled itself in China and entered a long-term rivalry with Japan for power in the Pacific, a competition that would culminate thirty years later in World War II.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

What factors constrained and guided U.S. actions in Asia and in Latin America?