America’s History: Printed Page 682

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 621

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 602

The United States and Latin America

Roosevelt famously argued that the United States should “speak softly and carry a big stick.” By “big stick,” he meant naval power, and rapid access to two oceans required a canal. European powers conceded the United States’s “paramount interest” in the Caribbean. Freed by Britain’s surrender of canal-building rights in the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty (1901), Roosevelt persuaded Congress to authorize $10 million, plus future payments of $250,000 per year, to purchase from Colombia a six-mile strip of land across Panama, a Colombian province.

Furious when Colombia rejected this proposal, Roosevelt contemplated outright seizure of Panama but settled on a more roundabout solution. Panamanians, long separated from Colombia by remote jungle, chafed under Colombian rule. The United States lent covert assistance to an independence movement, triggering a bloodless revolution. On November 6, 1903, the United States recognized the new nation of Panama; two weeks later, it obtained a perpetually renewable lease on a canal zone. Roosevelt never regretted the venture, though in 1922 the United States paid Colombia $25 million as a kind of conscience money.

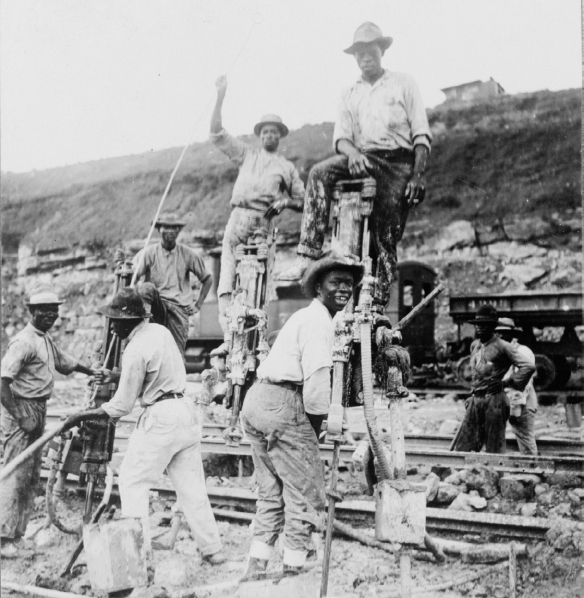

To build the canal, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers hired 60,000 laborers, who came from many countries to clear vast swamps, excavate 240 million cubic yards of earth, and construct a series of immense locks. The project, a major engineering feat, took eight years and cost thousands of lives among the workers who built it. Opened in 1914, the Panama Canal gave the United States a commanding position in the Western Hemisphere.

Meanwhile, arguing that instability invited European intervention, Roosevelt announced in 1904 that the United States would police all of the Caribbean (Map 21.2). This so-called Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine actually turned that doctrine upside down: instead of guaranteeing that the United States would protect its neighbors from Europe and help preserve their independence, it asserted the United States’s unrestricted right to regulate Caribbean affairs. The Roosevelt Corollary was not a treaty but a unilateral declaration sanctioned only by America’s military and economic might. Citing it, the United States intervened regularly in Caribbean and Central American nations over the next three decades.

Entering office in 1913, Democratic president Woodrow Wilson criticized his predecessors’ foreign policy. He pledged that the United States would “never again seek one additional foot of territory by conquest.” This stance appealed to anti-imperialists in the Democratic base, including longtime supporters of William Jennings Bryan. But the new president soon showed that, when American interests called for it, his actions were not so different from those of Roosevelt and Taft.

Since the 1870s, Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz had created a friendly climate for American companies that purchased Mexican plantations, mines, and oil fields. By the early 1900s, however, Díaz feared the extraordinary power of these foreign interests and began to nationalize — reclaim — key resources. American investors who faced the loss of Mexican holdings began to back Francisco Madero, an advocate of constitutional government who was friendly to U.S. interests. In 1911, Madero forced Díaz to resign and proclaimed himself president. Thousands of poor Mexicans took this opportunity to mobilize rural armies and demand more radical change. Madero’s position was weak, and several strongmen sought to overthrow him; in 1913, he was deposed and murdered by a leading general. Immediately, several other military men vied for control.

Wilson, fearing that the unrest threatened U.S. interests, decided to intervene in the emerging Mexican Revolution. On the pretext of a minor insult to the navy, he ordered U.S. occupation of the port of Veracruz on April 21, 1914, at the cost of 19 American and 126 Mexican lives. Though the intervention helped Venustiano Carranza, the revolutionary leader whom Wilson most favored, Carranza protested it as illegitimate meddling in Mexican affairs. Carranza’s forces, after nearly engaging the Americans themselves, entered Mexico City in triumph a few months later. Though Wilson had supported this outcome, his interference caused lasting mistrust.

Carranza’s victory did not subdue revolutionary activity in Mexico. In 1916, General Francisco “Pancho” Villa — a thug to his enemies, but a heroic Robin Hood to many poor Mexicans — crossed the U.S.-Mexico border, killing sixteen American civilians and raiding the town of Columbus, New Mexico. Wilson sent 11,000 troops to pursue Villa, a force that soon resembled an army of occupation in northern Mexico. Mexican public opinion demanded withdrawal as armed clashes broke out between U.S. and Mexican troops. At the brink of war, both governments backed off and U.S. forces departed. But policymakers in Washington had shown their intention to police not only the Caribbean and Central America but also Mexico when they deemed it necessary.