America’s History: Printed Page 688

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 629

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 610

War on the Home Front

In the United States, opponents of the war were a minority. Helping the Allies triggered an economic boom that benefitted farmers and working people. Many progressives also supported the war, hoping Wilson’s ideals and wartime patriotism would renew Americans’ attention to reform. But the war bitterly disappointed them. Rather than enhancing democracy, it chilled the political climate as government agencies tried to enforce “100 percent loyalty.”

Mobilizing the Economy American businesses made big bucks from World War I. As grain, weapons, and manufactured goods flowed to Britain and France, the United States became a creditor nation. Moreover, as the war drained British financial reserves, U.S. banks provided capital for investments around the globe.

Government powers expanded during wartime, with new federal agencies overseeing almost every part of the economy. The War Industries Board (WIB), established in July 1917, directed military production. After a fumbling start that showed the limits of voluntarism, the Wilson administration reorganized the board and placed Bernard Baruch, a Wall Street financier and superb administrator, at its head. Under his direction, the WIB allocated scarce resources among industries, ordered factories to convert to war production, set prices, and standardized procedures. Though he could compel compliance, Baruch preferred to win voluntary cooperation. A man of immense charm, he usually succeeded — helped by the lucrative military contracts at his disposal. Despite higher taxes, corporate profits soared, as military production sustained a boom that continued until 1920.

Some federal agencies took dramatic measures. The National War Labor Board (NWLB), formed in April 1918, established an eight-hour day for war workers with time-and-a-half pay for overtime, and it endorsed equal pay for women. In return for a no-strike pledge, the NWLB also supported workers’ right to organize — a major achievement for the labor movement. The Fuel Administration, meanwhile, introduced daylight saving time to conserve coal and oil. In December 1917, the Railroad Administration seized control of the nation’s hodgepodge of private railroads, seeking to facilitate rapid movement of troops and equipment — an experiment that had, at best, mixed results.

Perhaps the most successful wartime agency was the Food Administration, created in August 1917 and led by engineer Herbert Hoover. With the slogan “Food will win the war,” Hoover convinced farmers to nearly double their acreage of grain. This increase allowed a threefold rise in food exports to Europe. Among citizens, the Food Administration mobilized a “spirit of self-denial” rather than mandatory rationing. Female volunteers went from door to door to persuade housekeepers to observe “Wheatless” Mondays and “Porkless” Thursdays. Hoover, a Republican, emerged from the war as one of the nation’s most admired public figures.

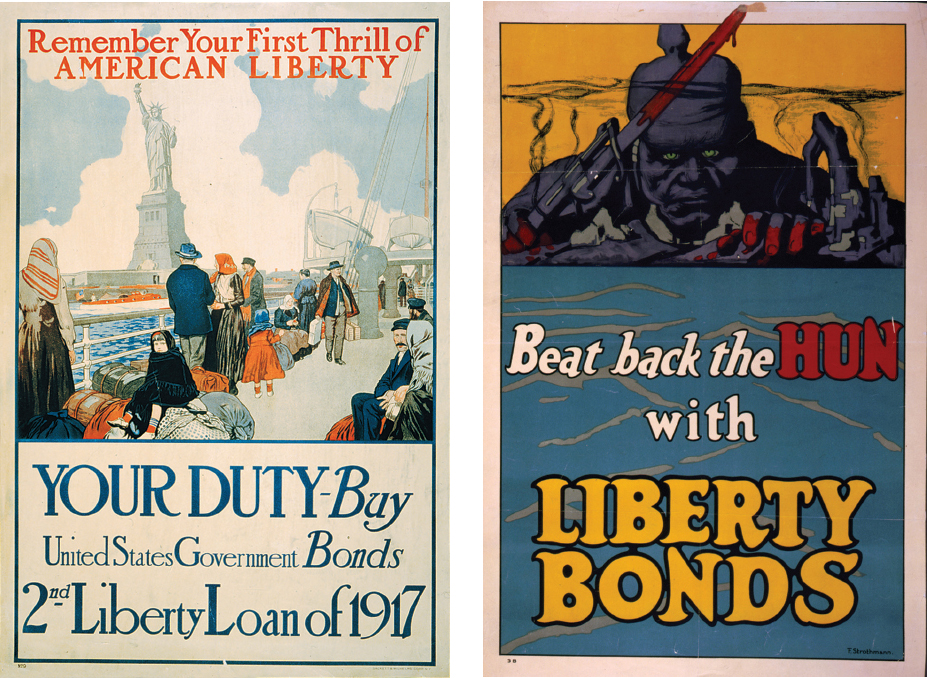

Promoting National Unity Suppressing wartime dissent became a near obsession for President Wilson. In April 1917, Wilson formed the Committee on Public Information (CPI), a government propaganda agency headed by journalist George Creel. Professing lofty goals — educating citizens about democracy, assimilating immigrants, and ending the isolation of rural life — the committee set out to mold Americans into “one white-hot mass” of war patriotism. The CPI touched the lives of nearly all civilians. It distributed seventy-five million pieces of literature and enlisted thousands of volunteers — Four-Minute Men — to deliver short prowar speeches at movie theaters.

The CPI also pressured immigrant groups to become “One Hundred Percent Americans.” German Americans bore the brunt of this campaign (Thinking Like a Historian). With posters exhorting citizens to root out German spies, a spirit of conformity pervaded the home front. A quasi-vigilante group, the American Protective League, mobilized about 250,000 “agents,” furnished them with badges issued by the Justice Department, and trained them to spy on neighbors and coworkers. In 1918, members of the league led violent raids against draft evaders and peace activists. Government propaganda helped rouse a nativist hysteria that lingered into the 1920s.

Congress also passed new laws to curb dissent. Among them was the Sedition Act of 1918, which prohibited any words or behavior that might “incite, provoke, or encourage resistance to the United States, or promote the cause of its enemies.” Because this and an earlier Espionage Act (1917) defined treason loosely, they led to the conviction of more than a thousand people. The Justice Department prosecuted members of the Industrial Workers of the World, whose opposition to militarism threatened to disrupt war production of lumber and copper. When a Quaker pacifist teacher in New York City refused to teach a prowar curriculum, she was fired. Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs was sentenced to ten years in jail for the crime of arguing that wealthy capitalists had started the conflict and were forcing workers to fight.

Federal courts mostly supported the acts. In Schenck v. United States (1919), the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a socialist who was jailed for circulating pamphlets that urged army draftees to resist induction. The justices followed this with a similar decision in Abrams v. United States (1919), ruling that authorities could prosecute speech they believed to pose “a clear and present danger to the safety of the country.” In an important dissent, however, Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and Louis Brandeis objected to the Abrams decision. Holmes’s probing questions about the definition of “clear and present danger” helped launch twentieth-century legal battles over free speech and civil liberties.

Great Migrations World War I created tremendous economic opportunities at home. Jobs in war industries drew thousands of people to the cities. With so many men in uniform, jobs in heavy industry opened for the first time to African Americans, accelerating the pace of black migration from South to North. During World War I, more than 400,000 African Americans moved to such cities as St. Louis, Chicago, New York, and Detroit, in what became known as the Great Migration. The rewards were great, and taking war jobs could be a source of patriotic pride. “If it hadn’t been for the negro,” a Carnegie Steel manager later recalled, “we could hardly have carried on our operations.”

Blacks in the North encountered discrimination in jobs, housing, and education. But in the first flush of opportunity, most celebrated their escape from the repressive racism and poverty of the South. “It is a matter of a dollar with me and I feel that God made the path and I am walking therein,” one woman reported to her sister back home. “Tell your husband work is plentiful here.” “I just begin to feel like a man,” wrote another migrant to a friend in Mississippi. “My children are going to the same school with the whites. …Will vote the next election and there isn’t any ‘yes sir’ and ‘no sir’ — it’s all yes and no and Sam and Bill.”

Wartime labor shortages prompted Mexican Americans in the Southwest to leave farmwork for urban industrial jobs. Continued political instability in Mexico, combined with increased demand for farmworkers in the United States, also encouraged more Mexicans to move across the border. Between 1917 and 1920, at least 100,000 Mexicans entered the United States; despite discrimination, large numbers stayed. If asked why, many might have echoed the words of an African American man who left New Orleans for Chicago: they were going “north for a better chance.” The same was true for Puerto Ricans such as Jésus Colón, who also confronted racism. “I came to New York to poor pay, long hours, terrible working conditions, discrimination even in the slums and in the poor paying factories,” Colón recalled, “where the bosses very dexterously pitted Italians against Puerto Ricans and Puerto Ricans against American Negroes and Jews.”

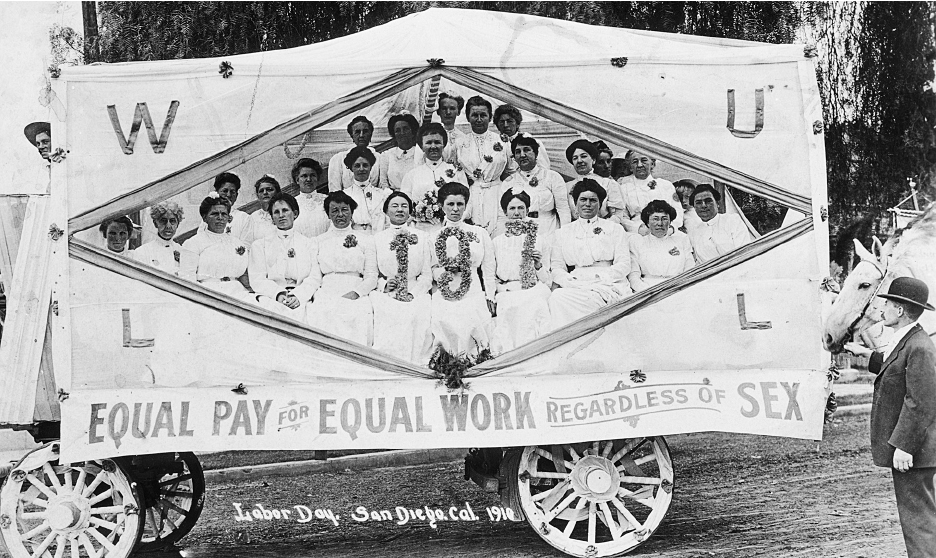

Women were the largest group to take advantage of wartime job opportunities. About 1 million women joined the paid labor force for the first time, while another 8 million gave up low-wage service jobs for higher-paying industrial work. Americans soon got used to the sight of female streetcar conductors, train engineers, and defense workers. Though most people expected these jobs to return to men in peacetime, the war created a new comfort level with women’s employment outside the home — and with women’s suffrage.

Women’s Voting Rights The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) threw the support of its 2 million members wholeheartedly into the war effort. Its president, Carrie Chapman Catt, declared that women had to prove their patriotism to win the ballot. NAWSA members in thousands of communities promoted food conservation and distributed emergency relief through organizations such as the Red Cross.

Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party (NWP) took a more confrontational approach. Paul was a Quaker who had worked in the settlement movement and earned a PhD in political science. Finding as a NAWSA lobbyist that congressmen dismissed her, Paul founded the NWP in 1916. Inspired by militant British suffragists, the group began in July 1917 to picket the White House. Standing silently with their banners, Paul and other NWP activists faced arrest for obstructing traffic and were sentenced to seven months in jail. They protested by going on a hunger strike, which prison authorities met with forced feeding. Public shock at the women’s treatment drew attention to the suffrage cause.

Impressed by NAWSA’s patriotism and worried by the NWP’s militancy, the antisuffrage Wilson reversed his position. In January 1918, he urged support for woman suffrage as a “war measure.” The constitutional amendment quickly passed the House of Representatives; it took eighteen months to get through the Senate and another year to win ratification by the states. On August 26, 1920, when Tennessee voted for ratification, the Nineteenth Amendment became law. The state thus joined Texas as one of two ex-Confederate states to ratify it. In most parts of the South, the measure meant that white women began to vote: in this Jim Crow era, African American women’s voting rights remained restricted along with men’s.

In explaining suffragists’ victory, historians have debated the relative effectiveness of Catt’s patriotic strategy and Paul’s militant protests. Both played a role in persuading Wilson and Congress to act, but neither might have worked without the extraordinary impact of the Great War. Across the globe, before 1914, the only places where women had full suffrage were New Zealand, Australia, Finland, and Norway. After World War I, many nations moved to enfranchise women. The new Soviet Union acted first, in 1917, with Great Britain and Canada following in 1918; by 1920, the measure had passed in Germany, Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary as well as the United States. (Major exceptions were France and Italy, where women did not gain voting rights until after World War II, and Switzerland, which held out until 1971.) Thus, while World War I introduced modern horrors on the battlefield — machine guns and poison gas — it brought some positive results at home: economic opportunity and women’s political participation.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

What were the different effects of African Americans’, Mexican Americans’, and women’s civilian mobilization during World War I?