America’s History: Printed Page 697

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 635

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 616

The Fate of Wilson’s Ideas

The peace conference included ten thousand representatives from around the globe, but leaders of France, Britain, and the United States dominated the proceedings. When the Japanese delegation proposed a declaration for equal treatment of all races, the Allies rejected it. Similarly, the Allies ignored a global Pan-African Congress, organized by W. E. B. Du Bois and other black leaders; they snubbed Arab representatives who had been military allies during the war. Even Italy’s prime minister — included among the influential “Big Four,” because in 1915 Italy had switched to the Allied side — withdrew from the conference, aggrieved at the way British and French leaders marginalized him. The Allies excluded two key players: Russia, because they distrusted its communist leaders, and Germany, because they planned to dictate terms to their defeated foe. For Wilson’s “peace among equals,” it was a terrible start.

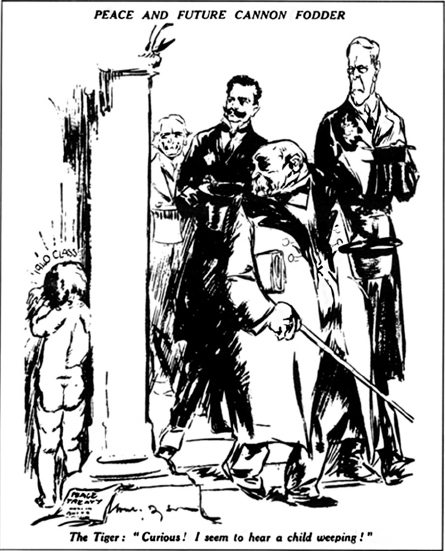

Prime Minister David Lloyd George of Britain and Premier Georges Clemenceau of France imposed harsh punishments on Germany. Unbeknownst to others at the time, they had already made secret agreements to divide up Germany’s African colonies and take them as spoils of war. At Versailles, they also forced the defeated nation to pay $33 billion in reparations and surrender coal supplies, merchant ships, valuable patents, and even territory along the French border. These terms caused keen resentment and economic hardship in Germany, and over the following two decades they helped lead to World War II.

Given these conditions, it is remarkable that Wilson influenced the Treaty of Versailles as much as he did. He intervened repeatedly to soften conditions imposed on Germany. In accordance with the Fourteen Points, he worked with the other Allies to fashion nine new nations, stretching from the Baltic to the Mediterranean (Map 21.4). These were intended as a buffer to protect Western Europe from communist Russia; the plan also embodied Wilson’s principle of self-determination for European states. Elsewhere in the world, the Allies dismantled their enemies’ empires but did not create independent nations, keeping colonized people subordinate to European power. France, for example, refused to give up its long-standing occupation of Indochina; Clemenceau’s snub of future Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, who sought representation at Versailles, had grave long-term consequences for both France and the United States.

The establishment of a British mandate in Palestine (now Israel) also proved crucial. During the war, British foreign secretary Sir Arthur Balfour had stated that his country would work to establish there a “national home for the Jewish people,” with the condition that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” Under the British mandate, thousands of Jews moved to Palestine and purchased land, in some cases evicting Palestinian tenants. As early as 1920, riots erupted between Jews and Palestinians — a situation that, even before World War II, escalated beyond British control.

The Versailles treaty thus created conditions for horrific future bloodshed, and it must be judged one of history’s great catastrophes. Balfour astutely described Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Wilson as “all-powerful, all-ignorant men, sitting there and carving up continents.” Wilson, however, remained optimistic as he returned home, even though his health was beginning to fail. The president hoped the new League of Nations, authorized by the treaty, would moderate the settlement and secure peaceful resolutions of other disputes. For this to occur, U.S. participation was crucial.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

In what ways did the Treaty of Versailles embody — or fail to embody — Wilson’s Fourteen Points?