America’s History: Printed Page 712

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 647

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 630

Culture Wars

By 1929, ninety-three U.S. cities had populations of more than 100,000. New York City’s population exceeded 7 million; Los Angeles’s had exploded to 1.2 million. The lives and beliefs of urban Americans often differed dramatically from those in small towns and farming areas. Native-born rural Protestants, faced with a dire perceived threat, rallied in the 1920s to protect what they saw as American values.

Prohibition Rural and native-born Protestants started the decade with the achievement of a longtime goal: national prohibition of liquor. Wartime anti-German prejudice was a major spur. Since breweries like Pabst and Anheuser-Busch were owned by German Americans, many citizens decided it was unpatriotic to drink beer. Mobilizing the economy for war, Congress also limited brewers’ and distillers’ use of barley and other scarce grains, causing consumption to decline. The decades-long prohibition campaign culminated with Congress’s passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1917. Ratified over the next two years by nearly every state and taking effect in January 1920, the amendment prohibited “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” anywhere in the United States.

Defenders hailed prohibition as a victory for health, morals, and Christian values. In urban areas, though, thousands flagrantly ignored the law. Patrons flocked to urban speakeasies, or illegal drinking sites, which flourished in almost every Chicago neighborhood; one raid on a South Side speakeasy yielded 200,000 gallons of alcohol. Profits from the secret clubs enriched notorious gangsters such as Chicago’s Al Capone and New York’s Jack Diamond.

In California, Arizona, and Texas, tens of thousands of Americans streamed “south of the border.” Mexico regulated liquor but kept it legal (along with gambling, drugs, and prostitution), leading to the rise of booming vice towns such as Tijuana and Mexicali, places that had been virtually uninhabited before 1900. U.S. nightclub owners in these cities included such prominent figures as African American boxer Jack Johnson. By 1928, the American investors who built a $10 million resort, racetrack, and casino in Tijuana became known as border barons. Prohibitionists were outraged by Americans’ circumventions of the law. Religious leaders on both sides of the border denounced illegal drinking — but profits were staggering. The difficulties of enforcing prohibition contributed to its repeal in 1933.

Evolution in the Schools At the state and local levels, controversy erupted as fundamentalist Protestants sought to mandate school curricula based on the biblical account of creation. In 1925, Tennessee’s legislature outlawed the teaching of “any theory that denies the story of the Divine creation of man as taught in the Bible, [and teaches] instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), formed during the Red Scare to protect free speech rights, challenged the law’s constitutionality. The ACLU intervened in the trial of John T. Scopes, a high school biology teacher who taught the theory of evolution to his class and faced a jail sentence for doing so. The case attracted national attention because Clarence Darrow, a famous criminal lawyer, defended Scopes, while William Jennings Bryan, the three-time Democratic presidential candidate, spoke for the prosecution.

Journalists dubbed the Scopes trial “the monkey trial.” This label referred both to Darwin’s argument that human beings and other primates share a common ancestor and to the circus atmosphere at the trial, which was broadcast live over a Chicago radio station. (Proving that urbanites had their own prejudices, acerbic critic H. L. Mencken dismissed antievolutionists as “gaping primates of the upland valleys,” implying that they had not evolved.) The jury took only eight minutes to deliver its verdict: guilty. Though the Tennessee Supreme Court later overturned Scopes’s conviction, the law remained on the books for more than thirty years.

Nativism Some native-born Protestants pointed to immigration as the primary cause of what they saw as America’s moral decline. A nation of 105 million people had added more than 23 million immigrants over the previous four decades; the newcomers included many Catholics and Jews from Southern and Eastern Europe, whom one Maryland congressman referred to as “indigestible lumps” in the “national stomach.” Such attitudes recalled hostility toward Irish and Germans in the 1840s and 1850s. In this case, they fueled a momentous shift in immigration policy. “America must be kept American,” President Coolidge declared in 1924. Congress had banned Chinese immigration in 1882, and Theodore Roosevelt had negotiated a so-called gentleman’s agreement that limited Japanese immigration in 1907. Now nativists charged that there were also too many European arrivals, some of whom undermined Protestantism and imported anarchism, socialism, and other radical doctrines. Responding to this pressure, Congress passed emergency immigration restrictions in 1921 and a permanent measure three years later. The National Origins Act (1924) used backdated census data to establish a baseline: in the future, annual immigration from each country could not exceed 2 percent of that nationality’s percentage of the U.S. population as it had stood in 1890. Since only small numbers of Italians, Greeks, Poles, Russians, and other Southern and Eastern European immigrants had arrived before 1890, the law drastically limited immigration from those places. In 1929, Congress imposed even more restrictive quotas, setting a cap of 150,000 immigrants per year from Europe and continuing to ban most immigrants from Asia.

The new laws, however, permitted unrestricted immigration from the Western Hemisphere. As a result, Latin Americans arrived in increasing numbers, finding jobs in the West that had gone to other immigrants before exclusion. More than 1 million Mexicans entered the United States between 1900 and 1930, including many during World War I. Nativists lobbied Congress to cut this flow; so did labor leaders, who argued that impoverished migrants lowered wages for other American workers. But Congress heeded the pleas of employers, especially farmers in Texas and California, who wanted cheap labor. Only the Great Depression cut off migration from Mexico.

Other anti-immigrant measures emerged at the state level. In 1913, by an overwhelming majority, California’s legislature had passed a law declaring that “aliens ineligible to citizenship” could not own “real property.” The aim was to discourage Asians, especially Japanese immigrants, from owning land, though some had lived in the state for decades and built up prosperous farms. In the wake of World War I, California tightened these laws, making it increasingly difficult for Asian families to establish themselves. California, Washington, and Hawaii also severely restricted any school that taught Japanese language, history, or culture. Denied both citizenship and land rights, Japanese Americans would be in a vulnerable position at the outbreak of World War II, when anti-Japanese hysteria swept the United States.

The National Klan The 1920s brought a nationwide resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), the white supremacist group formed in the post-Civil War South. Soon after the premiere of Birth of a Nation (1915), a popular film glorifying the Reconstruction-era Klan, a group of southerners gathered on Georgia’s Stone Mountain to revive the group. With its blunt motto, “Native, white, Protestant supremacy,” the Klan recruited supporters across the country (Thinking Like a Historian). KKK members did not limit their harassment to blacks but targeted immigrants, Catholics, and Jews as well, with physical intimidation, arson, and economic boycotts.

At the height of its power, the Klan wielded serious political clout and counted more than three million members, including many women. The Klan’s mainstream appeal was illustrated by President Woodrow Wilson’s public praise for Birth of a Nation. Though the Klan declined nationally after 1925, robbed of a potent issue by passage of the anti-immigration bill, it remained strong in the South, and pockets of KKK activity persisted in all parts of the country (Map 22.1). Klan activism lent a menacing cast to political issues. Some local Klansmen, for example, cooperated with members of the Anti-Saloon League to enforce prohibition laws through threats and violent attacks.

The rise of the Klan was part of an ugly trend that began before World War I and extended into the 1930s. In 1915, for example, rising anti-Semitism was marked by the lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory supervisor in Marietta, Georgia, who was wrongly accused of the rape and murder of a thirteen-year-old girl. The rise of the national Klan helped prepare the way for white supremacist movements of the 1930s, such as the Los Angeles-based Silver Legion, a fringe paramilitary group aligned with Hitler’s Nazis. Far more influential were major figures such as industrialist Henry Ford, whose Dearborn Independent railed against immigrants and warned that members of “the proud Gentile race” must arm themselves against a Jewish conspiracy aimed at world domination. Challenged by critics, Ford issued an apology in 1927 and admitted that his allegations had been based on “gross forgeries.” But with his paper’s editorials widely circulated by the Klan and other groups, considerable long-term damage had been done.

The Election of 1928 Conflicts over race, religion, and ethnicity created the climate for a stormy presidential election in 1928. Democrats had traditionally drawn strength from white voters in the South and immigrants in the North: groups that divided over prohibition, immigration restriction, and the Klan. By 1928, the northern urban wing gained firm control. Democrats nominated Governor Al Smith of New York, the first presidential candidate to reflect the aspirations of the urban working class. A grandson of Irish peasants, Smith had risen through New York City’s Democratic machine to become a dynamic reformer. But he offended many small-town and rural Americans with his heavy New York accent and brown derby hat, which highlighted his ethnic working-class origins. Middle-class reformers questioned his ties to Tammany Hall; temperance advocates opposed him as a “wet.” But the governor’s greatest handicap was his religion. Although Smith insisted that his Catholic beliefs would not affect his duties as president, many Protestants opposed him. “No Governor can kiss the papal ring and get within gunshot of the White House,” vowed one Methodist bishop.

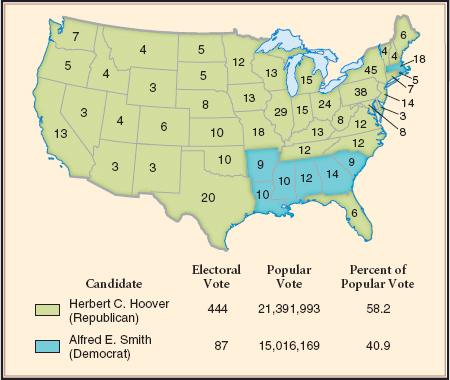

Smith proved no match for the Republican nominee, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, who embodied the technological promise of the modern age. Women who had mobilized for Hoover’s conservation campaigns during World War I enlisted as Hoover Hostesses, inviting friends to their homes to hear the candidate’s radio speeches. Riding on eight years of Republican prosperity, Hoover promised that individualism and voluntary cooperation would banish poverty. He won overwhelmingly, with 444 electoral votes to Smith’s 87 (Map 22.2). Because many southern Protestants refused to vote for a Catholic, Hoover carried five ex-Confederate states, breaking the Democratic “Solid South” for the first time since Reconstruction. Smith, though, carried industrialized Massachusetts and Rhode Island as well as the nation’s twelve largest cities, suggesting that urban voters were moving into the Democrats’ camp.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME

Question

How did debates over alcohol use, the teaching of evolution, immigration, anti-Semitism, and racism evolve in the 1920s?