America’s History: Printed Page 718

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 653

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 635

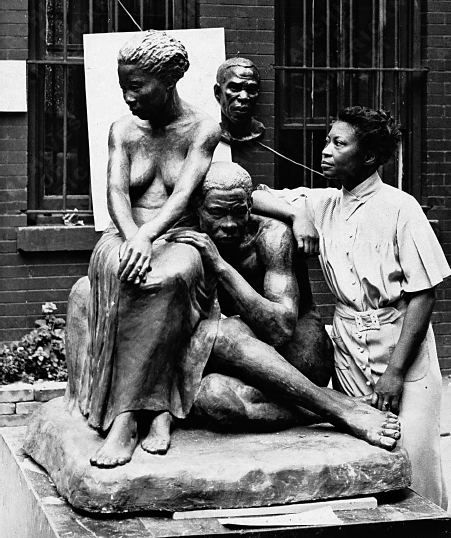

Harlem in Vogue

The Great Migration tripled New York’s black population in the decade after 1910. Harlem stood as “the symbol of liberty and the Promised Land to Negroes everywhere,” as one minister put it. Talented African Americans flocked to the district, where they created bold new art forms and asserted ties to Africa.

Black Writers and Artists Poet Langston Hughes captured the upbeat spirit of the Harlem Renaissance when he asserted, “I am a Negro — and beautiful.” Other writers and artists also championed race pride. Claude McKay and Jean Toomer represented in fiction what philosopher Alain Locke called, in an influential 1925 book, The New Negro. Painter Jacob Lawrence, who had grown up in crowded tenement districts of the urban North, used bold shapes and vivid colors to portray the daily life, aspirations, and suppressed anger of African Americans.

No one embodied the energy and optimism of the Harlem Renaissance more than Zora Neale Hurston. Born in the prosperous black community of Eatonville, Florida, Hurston had been surrounded as a child by examples of achievement, though she struggled later with poverty and isolation. In contrast to some other black thinkers, Hurston believed African American culture could be understood without heavy emphasis on the impact of white oppression. After enrolling at Barnard College and studying with anthropologist Franz Boas, Hurston traveled through the South and the Caribbean for a decade, documenting folklore, songs, and religious beliefs. She incorporated this material into her short stories and novels, celebrating the humor and spiritual strength of ordinary black men and women. Like other work of the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston’s stories and novels sought to articulate what it meant, as black intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois wrote, “to be both a Negro and an American.”

Jazz To millions of Americans, the most famous product of the Harlem Renaissance was jazz. Though the origins of the word are unclear, many historians believe it was a slang term for sex — an etymology that makes sense, given the music’s early association with urban vice districts. As a musical form, jazz coalesced in New Orleans and other parts of the South before World War I. Borrowing from blues, ragtime, and other popular forms, jazz musicians developed an ensemble style in which performers, keeping a rapid ragtime beat, improvised around a basic melodic line. The majority of early jazz musicians were black, but white performers, some of whom had more formal training, injected elements of European concert music.

In the 1920s, as jazz spread nationwide, musicians developed its signature mode, the improvised solo. The key figure in this development was trumpeter Louis Armstrong. A native of New Orleans, Armstrong learned his craft playing in the saloons and brothels of the city’s vice district. Like tens of thousands of other African Americans he moved north, settling in Chicago in 1922. Armstrong showed an inexhaustible capacity for melodic invention, and his dazzling solos inspired other musicians. By the late 1920s, soloists became the celebrities of jazz, thrilling audiences with their improvisational skill.

As jazz spread, it followed the routes of the Great Migration from the South to northern and midwestern cities, where it met consumers primed to receive it. Most cities had plentiful dance halls where jazz could be featured. Radio also helped popularize jazz, with the emerging record industry marketing the latest tunes. As white listeners flocked to ballrooms and clubs to hear Duke Ellington and other stars, Harlem became the hub of this commercially lucrative jazz. Those who hailed “primitive” black music rarely suspended their racial condescension: visiting a mixed-race club became known as “slumming.”

The recording industry soon developed race records specifically aimed at urban working-class blacks. The breakthrough came in 1920, when Otto K. E. Heinemann, a producer who sold immigrant records in Yiddish, Swedish, and other languages, recorded singer Mamie Smith performing “Crazy Blues.” This smash hit prompted big recording labels like Columbia and Paramount to copy Heinemann’s approach. Yet, while its marketing reflected the segregation of American society, jazz brought black music to the center stage of American culture. It became the era’s signature music, so much so that novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald dubbed the 1920s the “Jazz Age.”

Marcus Garvey and the UNIA Harlem’s creative energy generated broad political aspirations. The Harlem-based Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), led by charismatic Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, arose in the 1920s to mobilize African American workers and champion black separatism. Garvey urged followers to move to Africa, arguing that people of African descent would never be treated justly in white-run countries.

The UNIA soon claimed four million followers, including many recent migrants to northern cities. It published a newspaper, Negro World, and solicited funds for the Black Star steamship company, which Garvey created as an enterprise that would foster trade with the West Indies and carry American blacks to Africa. But the UNIA declined as quickly as it had risen. In 1925, Garvey was imprisoned for mail fraud because of his solicitations for the Black Star Line. President Coolidge commuted his sentence but ordered his deportation to Jamaica. Without Garvey’s leadership, the movement collapsed.

However, the UNIA left a legacy of activism, especially among the working class. Garvey and his followers represented an emerging pan-Africanism. They argued that people of African descent, in all parts of the world, had a common destiny and should cooperate in political action. Several developments contributed to this ideal: black men’s military service in Europe during World War I, the Pan-African Congress that had sought representation at the Versailles treaty table, protests against U.S. occupation of Haiti, and modernist experiments in literature and the arts. One African American historian wrote in 1927, “The grandiose schemes of Marcus Garvey gave to the race a consciousness such as it had never possessed before. The dream of a united Africa, not less than a trip to France, challenged the imagination.”

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES

Question

How did the Great Migration lead to flourishing African American culture, politics, and intellectual life, and what form did these activities take?