America’s History: Printed Page 721

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 657

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 638

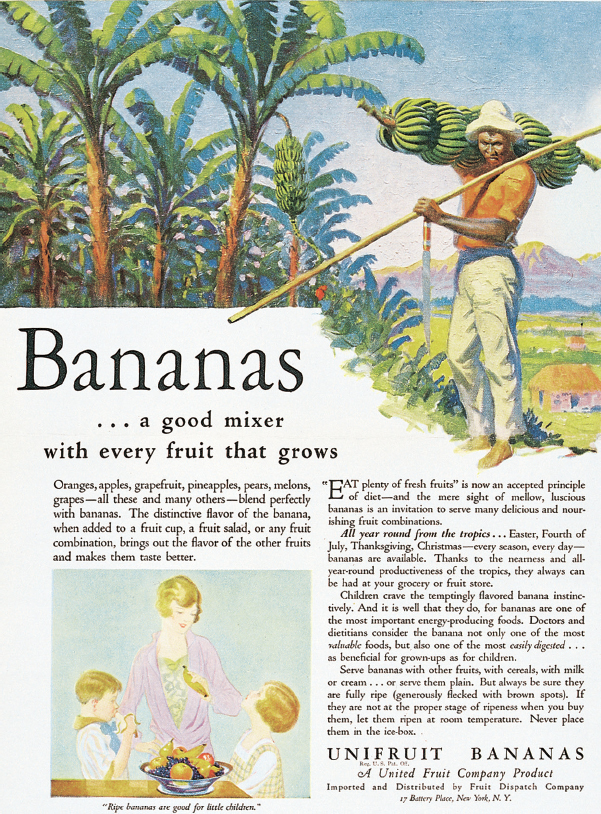

Consumer Culture

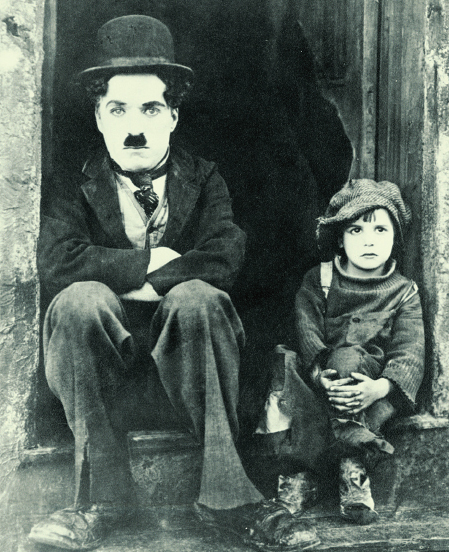

In middle-class homes, Americans of the 1920s sat down to a breakfast of Kellogg’s corn flakes before getting into Ford Model Ts to work or shop at Safeway. On weekends, they might head to the local theater to see the newest Charlie Chaplin film. By 1929, electric refrigerators and vacuum cleaners came into use in affluent homes; 40 percent of American households owned a radio. The advertising industry reached new levels of ambition and sophistication, entering what one historian calls the era of the “aggressive hard sell.” The 1920s gave birth, for example, to fashion modeling and style consulting. “Sell them their dreams,” one radio announcer urged advertisers in 1923. “People don’t buy things to have things. … They buy hope — hope of what your merchandise will do for them.”

In practice, participation in consumer culture was as contested as the era’s politics. It was no accident that white mobs in the Tulsa race riot plundered radios and phonograph players from prosperous African American homes: the message was that whites deserved such items and blacks did not. But neither prosperity nor poverty was limited by race. Surrounded by exhortations to indulge in luxuries, millions of working-class Americans barely squeaked by, with wives and mothers often working to pay for basic necessities. In times of crisis, some families sold their furniture, starting with pianos and phonographs and continuing, if necessary, to dining tables and beds. In the Los Angeles suburb of South Gate, white working-class men secured jobs in the steel and automobile industries, but prices were high and families often found it difficult to make ends meet. Self-help was the watchword as families bartered with neighbors and used their yards to raise vegetables, rabbits, and chickens.

The lure of consumer culture created friction. Wives resented husbands who spent all their discretionary cash at the ballpark. Generational conflicts emerged, especially when wage-earning children challenged the expectation that their pay should go “all to mother.” In St. Louis, a Czech-born woman was exasperated when her son and daughter stopped contributing to rent and food and pooled their wages to buy a car. In Los Angeles, one fifteen-year-old girl spent her summer earning $2 a day at a local factory. Planning to enroll in business school, she spent $75 on dressy shoes and “a black coat with a red fox collar.” Her brother reported that “Mom is angry at her for ‘squandering’ so much money.”

Many poor and affluent families shared one thing in common: they stretched their incomes, small or large, through new forms of borrowing such as auto loans and installment plans. “Buy now, pay later,” said the ads, and millions did. Anyone, no matter how rich, could get into debt, but consumer credit was particularly perilous for those living on the economic margins. In Chicago, one Lithuanian man described his neighbor’s situation: “She ain’t got no money. Sure she buys on credit, clothes for the children and everything.” Such borrowing turned out to be a factor in the bust of 1929.

The Automobile No possession proved more popular than the automobile, a showpiece of modern consumer capitalism that revolutionized American life. Car sales played a major role in the decade’s economic boom: in one year, 1929, Americans spent $2.58 billion on automobiles. By the end of the decade, they owned 23 million cars — about 80 percent of the world’s automobiles — or an average of one for every six people.

The auto industry’s exuberant expansion rippled through the economy, with both positive and negative results. It stimulated steel, petroleum, chemical, rubber, and glass production and, directly or indirectly, created 3.7 million jobs. Highway construction became a billion-dollar-a-year enterprise, financed by federal subsidies and state gasoline taxes. Car ownership spurred urban sprawl and, in 1924, the first suburban shopping center: Country Club Plaza outside Kansas City, Missouri. But cars were expensive, and most Americans bought them on credit. This created risks not only for buyers but for the whole economy. Borrowers who could not pay off car loans lost their entire investment in the vehicle; if they defaulted, banks were left holding unpaid loans. Amid the boom of the 1920s, however, few worried about this result.

Cars changed the way Americans spent their leisure time, as proud drivers took their machines on the road. An infrastructure of gas stations, motels, and drive-in restaurants soon catered to drivers. Railroad travel faltered. The American Automobile Association, founded in 1902, estimated that by 1929 almost a third of the population took vacations by car. As early as 1923, Colorado had 247 autocamps. “I had a few days after I got my wheat cut,” reported one Kansas farmer, “so I just loaded my family … and lit out.” An elite Californian complained that automobile travel was no longer “aristocratic.” “The clerks and their wives and sweethearts,” observed a reporter, “driving through the Wisconsin lake country, camping at Niagara, scattering tin cans and pop bottles over the Rockies, made those places taboo for bankers.”

Hollywood Movies formed a second centerpiece of consumer culture. In the 1910s, the moviemaking industry had begun moving to southern California to take advantage of cheap land, sunshine, and varied scenery within easy reach. The large studios — United Artists, Paramount, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer — were run mainly by Eastern European Jewish immigrants like Adolph Zukor, who arrived from Hungary in the 1880s. Starting with fur sales, Zukor and a partner then set up five-cent theaters in Manhattan. “I spent a good deal of time watching the faces of the audience,” Zukor recalled. “With a little experience I could see, hear, and ‘feel’ the reaction to each melodrama and comedy.” Founding Paramount Pictures, Zukor signed emerging stars and produced successful feature-length films.

By 1920, Hollywood reigned as the world’s movie capital, producing nearly 90 percent of all films. Large, ornate movie palaces attracted both middle-class and working-class audiences. Idols such as Rudolph Valentino, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks set national trends in style. Thousands of young women followed the lead of actress Clara Bow, Hollywood’s famous flapper, who flaunted her boyish figure. Decked out in knee-length skirts, flappers shocked the older generation by smoking and wearing makeup.

Flappers represented only a tiny minority of women, but thanks to the movies and advertising, they became influential symbols of women’s sexual and social emancipation. In cities, young immigrant women eagerly bought makeup and the latest flapper fashions and went dancing to jazz. Jazz stars helped popularize the style among working-class African Americans. Mexican American teenagers joined the trend, though they usually found themselves under the watchful eyes of la dueña, the chaperone.

Politicians quickly grasped the publicity value of American radio and film to foreign relations. In 1919, with government support, General Electric spearheaded the creation of Radio Corporation of America (RCA) to expand U.S. presence in foreign radio markets. RCA — which had a federal appointee on its board of directors — emerged as a major provider of radio transmission in Latin America and East Asia. Meanwhile, by 1925, American films made up 95 percent of the movies screened in Britain, 80 percent in Latin America, and 70 percent in France (America Compared). The United States was experimenting with what historians call soft power — the exercise of popular cultural influence — as radio and film exports celebrated the American Dream.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT

Question

How did the radio, automobile, and Hollywood movies exemplify the opportunities and the risks of 1920s consumer culture?