America’s History: Printed Page 726

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 660

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 641

The Coming of the Great Depression

By 1927, strains on the economy began to show. Consumer lending had become the tenth-largest business in the country, topping $7 billion that year. Increasing numbers of Americans bought into the stock market, often with unrealistic expectations. One Yale professor proclaimed that stocks had reached a “permanently high plateau.” Corporate profits were so high that some companies, fully invested in their own operations, plowed excess earnings into the stock market. Other market players compounded risk by purchasing on margin. An investor might, for example, spend $20 of his own money and borrow $80 to buy a $100 share of stock, expecting to pay back the loan as the stock rose quickly in value. This worked as long as the economy grew and the stock market climbed. But those conditions did not last.

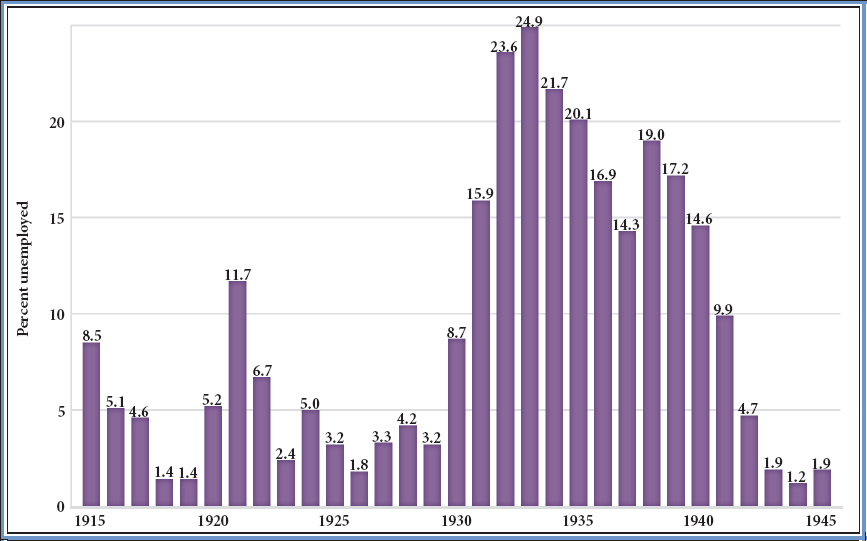

Yet when the stock market fell, in a series of plunges between October 25 and November 13, 1929, few onlookers understood the magnitude of the crisis. Cyclical downturns had been a familiar part of the industrializing economy since the panic of the 1830s; they tended to follow periods of rapid growth and speculation. A sharp recent recession, in 1921, had not triggered disaster. The market rose again in late 1929 and early 1930, and while a great deal of money had been lost, most Americans hoped the aftermath of the crash would be brief. In fact, the nation had entered the Great Depression. Over the next four years, industrial production fell 37 percent. Construction plunged 78 percent. Prices for crops and other raw materials, already low, fell by half. By 1932, unemployment had reached a staggering 24 percent (Figure 22.1).

A precipitous drop in consumer spending deepened the crisis. Facing hard times and unemployment, Americans cut back dramatically, creating a vicious cycle of falling demand and forfeited loans. In late 1930, several major banks went under, victims of overextended credit and reckless management. The following year, as industrial production slowed, a much larger wave of bank failures occurred, causing an even greater shock. Since the government did not insure bank deposits, accounts in failed banks simply vanished. Some people who had had steady jobs and comfortable savings found themselves broke and out of work.

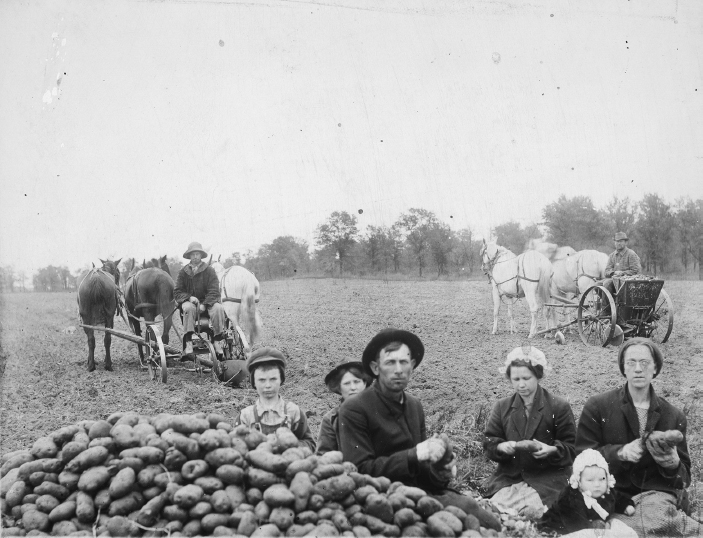

Not all Americans were devastated by the depression; the middle class did not disappear and the rich lived in accustomed luxury. But incomes plummeted even among workers who kept their jobs. Salt Lake City went bankrupt in 1931. Barter systems developed, as barbers traded haircuts for onions and potatoes and laborers worked for payment in eggs or pork. “We do not dare to use even a little soap,” reported one jobless Oregonian, “when it will pay for an extra egg, a few more carrots for our children.” “I would be only too glad to dig ditches to keep my family from going hungry,” wrote a North Carolina man.

Where did desperate people turn for aid? Their first hope lay in private charity, especially churches and synagogues. But by the winter of 1931, these institutions were overwhelmed, unable to keep pace with the extraordinary need. Only eight states provided even minimal unemployment insurance. There was no public support for the elderly, statistically among the poorest citizens. Few Americans had any retirement savings, and many who had saved watched their accounts erased by failing banks.

Even those who were not wiped out had to adapt to depression conditions. Couples delayed marriage and reduced the number of children they conceived. As a result, the marriage rate fell to a historical low, and by 1933 the birthrate dropped from 97 births per 1,000 women to 75. Often the responsibility for birth control fell to women. It was “one of the worst problems of women whose husbands were out of work,” a Californian told a reporter. Campaigns against hiring married women were common, on the theory that available jobs should go to male breadwinners. Three-quarters of the nation’s school districts banned married women from working as teachers — ignoring the fact that many husbands were less able to earn than ever before. Despite restrictions, female employment increased, as women expanded their financial contributions to their families in hard times.

The depression crossed regional boundaries, though its severity varied from place to place. Bank failures clustered heavily in the Midwest and plains, while areas dependent on timber, mining, and other extractive industries suffered catastrophic declines. Although southern states endured less unemployment because of their smaller manufacturing base, farm wages plunged. In many parts of the country, unemployment rates among black men stood at double that of white men; joblessness among African American women was triple that of white women.

By 1932, comprehending the magnitude of the crisis, Americans went to the ballot box and decisively rejected the probusiness, antiregulatory policies of the 1920s. A few years earlier, with business booming, politics had been so placid that people chuckled when President Coolidge disappeared on extended fishing trips. Now, Americans wanted bold action in Washington. Faced with the cataclysm of the Great Depression, Americans would transform their government and create a modern welfare state.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What domestic and global factors helped cause the Great Depression?